(Press-News.org) Naturally occurring electricity in our cells is key to how our bodies function, and that includes the healing of wounds.

And externally applied low-amplitude electric fields have been shown to help hard-to-heal chronic wounds, like those associated with diabetes, where there is insufficient blood supply and drug treatments are not effective. The externally applied electric field manipulates the body's naturally occurring electricity, such that the new vessels are formed, and blood supply to the wound is increased.

University of Cincinnati physics and biomedical engineering researchers recently tested for the most-effective magnitude and frequency when applying an external low-amplitude electric field to vascular cells, which are key to healing chronic wounds. Physics doctoral student Toloo Taghian will present the results at the March 3-7 American Physical Society meeting in Denver. The title of her presentation is "Co-Regulation of Cell Behavior by Electromagnetic Stimulus and Extracellular Environment."

The team discovered that high-frequency electrical stimulus, similar to that generated by cell phones and Wi-Fi networks, increased the growth of blood vessel networks by as much as 50 percent, while low-frequency electrical stimulus did not produce such an effect. As part of their work, the UC team has developed a specialized antenna to apply the electrical signals to a localized wound, and that design is now the subject of a provisional patent.

HOW HIGH-FREQUENCY ELECTRICITY AFFECTS VASCULAR CELL GROWTH

The high-frequency electrical stimulus is able to change the ionic environment surrounding the endothelial cells, which form the lining of blood vessels. Inside the cells, this stimulus can create links with proteins (proteins have existing charges that react with the applied electrical field) to activate pathway signals leading to growth in the capillary network. The high-frequency electrical stimulus also causes cells to produce chemicals called "growth factors" that help sustain growing vascular networks.

Said Taghian, "Electrical stimulation activates the pathway for angiogenesis (formation of new blood vessels), and the vascular network growth is enhanced. We can expect that, as a result, wound closure would be enhanced, leading to a faster healing."

The potential for electrical-based treatment of wounds is far reaching. Given the targeted, localized nature of such wound treatment, the application of electrical stimulus could replace or reduce the need for drug-based treatments which affect the entire body and may carry side effects. Importantly, such therapy could be applied using a hand-held device without the need to remove the wound dressing.

The stimulus frequency used by the team was as high as 7.5 billion cycles per second (Gigahertz, or GHz), and as low as 60 cycles per second (Hertz, or Hz), which is the same frequency used in 120V power outlets in the United States. The vascular tissue cells were exposed to the electrical fields for one hour per day for seven days, and the rate of wound healing was observed for 24 hours after each treatment.

INFORMATION:

In addition to Taghian, other members of the team are

Abdul Sheikh, a former UC doctoral student in biomedical engineering and now a post-doc at Yale University.

Daria Narmoneva, associate professor of biomedical engineering in UC's College of Engineering and Applied Science.

Andrei Kogan, associate professor of physics in UC's McMicken College of Arts and Sciences.

Mary Frances Locke, a former undergraduate student in physics in UC's McMicken College of Arts and Sciences.

Danielle Bourgeois, a former undergraduate from University of Oklahoma who attended a UC Engineering Research Experiences for Undergraduates program.

Support for this research was provided by the Department of Physics in the UC College of Arts and Sciences, the biomedical engineering program in the UC College of Engineering and Applied Science, the UC University Research Council (URC), UC Institute for Nanoscale Science and Technology, and the National Science Foundation.

UC research tests range of electrical frequencies that help heal chronic wounds

2014-03-04

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Cigarette smoking may cause physical changes in brains of young smokers, UCLA study shows

2014-03-04

The young, it turns out, smoke more than any other age group in America. Unfortunately, the period of life ranging from late adolescence to early adulthood is also a time when the brain is still developing.

Now, a small study from UCLA suggests a disturbing effect: Young adult smokers may experience changes in the structures of their brains due to cigarette smoking, dependence and craving. Even worse, these changes can occur in those who have been smoking for relatively short time. Finally, the study suggests that neurobiological changes that may result from smoking ...

Pitt public health analysis provides guidance on hospital community benefit programs

2014-03-04

PITTSBURGH, March 3, 2014 – A new analysis led by the University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health offers insights for nonprofit hospitals in implementing community health improvement programs.

In a special issue of the Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved that focuses on the Affordable Care Act (ACA), a multidisciplinary team of Pitt researchers explore published research on existing community benefit programs at U.S. hospitals and explain how rigorous implementation of such programs could help hospitals both meet federal requirements and ...

New study reveals insights on plate tectonics, the forces behind earthquakes, volcanoes

2014-03-04

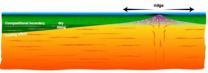

The Earth's outer layer is made up of a series of moving, interacting plates whose motion at the surface generates earthquakes, creates volcanoes and builds mountains. Geoscientists have long sought to understand the plates' fundamental properties and the mechanisms that cause them to move and drift, and the questions have become the subjects of lively debate.

A study published online Feb. 27 by the journal Science is a significant step toward answering those questions.

Researchers led by Caroline Beghein, assistant professor of earth, planetary and space sciences ...

Novel drug treatment protects primates from deadly Marburg virus

2014-03-04

For the first time, scientists have demonstrated the effectiveness of a small-molecule drug in protecting nonhuman primates from the lethal Marburg virus. Their work, published online in the journal Nature, is the result of a continuing collaboration between Army scientists and industry partners that also shows promise for treating a broad range of other viral diseases.

According to senior author Sina Bavari, the drug, known as BCX4430, protected cynomolgous macaques from Marburg virus infection when administered by injection as long as 48 hours post-infection. Bavari ...

Manufacturing a solution to planet-clogging plastics

2014-03-04

Researchers at Harvard's Wyss Institute have developed a method to carry out large-scale manufacturing of everyday objects – from cell phones to food containers and toys – using a fully degradable bioplastic isolated from shrimp shells. The objects exhibit many of the same properties as those created with synthetic plastics, but without the environmental threat. It also trumps most bioplastics on the market today in posing absolutely no threat to trees or competition with the food supply. The advance was reported online last week in Macromolecular Materials & Engineering. ...

Pediatric surgeons develop standards for children's surgical care in the United States

2014-03-04

Chicago (March 3, 2014): The American College of Surgeons (ACS) has published new comprehensive guidelines that define the resources the nation's surgical facilities need to perform operations effectively and safely in infants and children. The standards—published in the March issue of the Journal of the American College of Surgeons—also have the approval of the American Pediatric Surgical Association and the Society of Pediatric Anesthesia. Representatives of these organizations as well as invited leaders in other pediatric medical specialties, known as the Task Force ...

HPV vaccine provides significant protection against cervical abnormalities

2014-03-04

The HPV vaccine offers significant protection against cervical abnormalities in young women, suggests a paper published on bmj.com today.

The human papillomavirus (HPV) can cause warts, with some strains causing cervical cancer.

Australia was the first country to implement a publicly funded national vaccination programme in April 2007 and a 'catch-up' programme that ran until December 2009.

Studies have shown that the two HPV vaccines used to vaccinate young women prevent cervical lesions associated with HPV types including vulval and vaginal lesions and genital ...

Report describes Central Hardwoods forest vulnerabilities, climate change impacts

2014-03-04

ST. PAUL, Minn., March 4, 2014 – Higher temperatures, more heavy precipitation, and drought. It's all expected in the Central Hardwoods Region of southern Indiana, southern Illinois, and the Missouri Ozarks, according to a new report by the U.S. Forest Service, and partners that assesses the vulnerability of the region's forest ecosystems and its ability to adapt to a changing climate.

More than 30 scientists and forest managers contributed to the report, which is part of the Central Hardwoods Climate Change Response Framework, a collaboration of federal, state, academic ...

Exploring sexual orientation and intimate partner violence

2014-03-04

HUNTSVILLE, TX (3/4/14) -- Two studies at Sam Houston State University examined issues of sexual orientation and intimate partner violence, including its impact on substance abuse and physical and mental health as well as the effects of child abuse on its victims.

"We wanted to see how characteristics of the victims might differ based on if they were heterosexual or non-heterosexual," said Maria Koeppel, a Ph.D. student at the College of Criminal Justice, who coauthored the studies with Dr. Leana Bouffard. "These studies show the need to have specialized programs designed ...

New probes from Scripps research quantify folded and misfolded protein levels in cells

2014-03-04

LA JOLLA, CA – March 4, 2014 – Scientists at The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) have invented small-molecule folding probes that enable them to quantify functional, normally folded and disease-associated misfolded conformations (shapes) of a protein-of-interest in cells under different conditions.

Scientists have long needed better tools for making such measurements in cells, because protein misfolding is a major cause of damage to tissues. Disorders that feature excessive protein misfolding afflict millions of people worldwide and include Alzheimer's and Parkinson's ...