(Press-News.org) This news release is available in Portuguese.

Our intestines harbour an astronomical number of bacteria, around 100 times the number of cells in our body, known as the gut microbiota. These bacteria belong to thousands of species that co-exist, interact with each other and are key to our health. While it is clear that species imbalances may result in disease, it is unclear at what pace does each species in the gut evolves, a process that contributes to the chance of a particular innocuous species becoming harmful to the host.

In the latest issue of the scientific journal PLOS Genetics*, three research groups from Instituto Gulbenkian de Ciência (IGC; Portugal), led by Isabel Gordo, joint efforts to unveil, for the first time, how the bacteria Escherichia coli (E. coli), one of the first species to colonize the human gut at birth, adapts and evolves in the mouse intestine. The researchers have shown that E. coli with different advantageous mutations rapidly emerge and, consequently, a large genetic variation in this species is generated over time. Their results unravelled a layer of complexity of the gut microbiota, which has been unknown so far. This study demonstrates how rich the evolutionary dynamics of each bacteria is in a healthy animal and will be instrumental for the development of new strategies to fight disease by manipulating gut microbes.

It was unknown to Charles Darwin that the process of natural selection that he deduced from observing the diversity in the world surrounding him, could be taking place inside his own body. For several years evolution of bacteria has been studied in Petri dishes, which are highly artificial environments. The laboratories of Isabel Gordo, Karina Xavier and Jocelyne Demengeot, at IGC, joint their expertise in evolution, microbiology and immunology, respectively, and set out to study evolution of E. coli in its natural environment: the gut. They fed mice with E. coli and analysed mice's faeces for mutations that emerged during bacterial evolution inside the intestine. Their results indicate that many advantageous mutations occur and bacteria carrying different mutations compete for fixation in the gut. The evolution process is the outcome of this continuous competition where a large diversity of E. coli strains is observed.

In order to identify the genes important for the adaptation to the gut, the researchers analysed genetically the E. coli strains that emerged. Their results pointed out specific genes inactivation allowing bacteria to grow better in the presence of products generated by the host metabolism. They also reported changes of genes that regulate anaerobic respiration (a process required in environments low in oxygen like the gut). The researchers found that despite the high complexity of the natural environment studied – the intestine – the evolutionary process was highly reproducible as the same mutations occurred in populations of E. coli evolving in different mice.

"It is remarkable that we can study evolution with this level of quantitative precision in one of the most complex environments ever tackled", says Isabel Gordo. "The competitive war that appears to take place between emerging new strains of a given species will have to be further integrated with the variation observed between the different species inhabiting the gut along time. No doubt this opens room for many interesting future research studies of ecology and evolution in both healthy and non-healthy hosts."

Karina Xavier adds: "What most surprised me with these experiments was first, how fast these bacteria are evolving inside the mouse and therefore inside our bodies, and secondly, how reproducible the evolutionary path was. The fact that we observed the same mutations appearing over and over again every time we repeated this experiment will enable us to pin point the major factors controlling the microbiota in our gut, being the food we eat, our immune system or the microbes we encounter in the environment."

Jocelyne Demengeot says: "Most state of the art studies in Evolution and Ecology of bacteria are still conducted in vitro, in Petri dishes. Our long-term challenge, here proven feasible, is to move those fields to physiological situation, i.e to in vivo experimentation, in vertebrates. As for other fields of biomedical science, this approach is necessary to walk the scientific paths eventually leading to application for health and diseases."

INFORMATION:

The research was funded by the European Research Council under the European Community's Seventh Framework Programme, by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI; USA), and by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT; Portugal).

* Barroso-Batista, J, Sousa, A, Lourenço, M, Bergman, ML, Sobral, D, Demengeot, J, Xavier, KB, and Gordo, I. (2014) The first steps of adaptation of Escherichia coli to the gut are dominated by soft sweeps. PLOS Genetics 10 (3): e1004182. http://www.plosgenetics.org/doi/pgen.1004182

Fighting for survival in the gut: Unravelling the hidden variation of bacteria

2014-03-07

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Contacts better than permanent lenses for babies after cataract surgery

2014-03-06

For adults and children who undergo cataract surgery, implantation of an artificial lens is the standard of care. But a clinical trial suggests that for most infants, surgery followed by the use of contact lenses for several years—and an eventual lens implant—may be the better solution. The trial was funded in part by the National Eye Institute (NEI), a component of the National Institutes of Health.

A cataract is a clouding of the eye's lens, and can be removed through a safe, quick surgical procedure. After cataract removal, most adults and children receive a permanent ...

NASA's Hubble Telescope witnesses asteroid's mysterious disintegration

2014-03-06

NASA's Hubble Space Telescope has recorded the never-before-seen break-up of an asteroid into as many as 10 smaller pieces.

Fragile comets, comprised of ice and dust, have been seen falling apart as they near the sun, but nothing like this has ever before been observed in the asteroid belt.

"This is a rock, and seeing it fall apart before our eyes is pretty amazing," said David Jewitt of the University of California at Los Angeles, who led the astronomical forensics investigation.

The crumbling asteroid, designated P/2013 R3, was first noticed as an unusual, fuzzy-looking ...

Nearby star's icy debris suggests 'shepherd' planet

2014-03-06

VIDEO:

NASA Goddard's Aki Roberge explains how observations with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array in Chile tell us about poison gas, comet swarms and a hypothetical planet around Beta Pictoris....

Click here for more information.

An international team of astronomers exploring the disk of gas and dust around a nearby star have uncovered a compact cloud of poisonous gas formed by ongoing rapid-fire collisions among a swarm of icy, comet-like bodies. The researchers ...

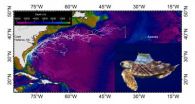

Study provides new information about the sea turtle 'lost years'

2014-03-06

MIAMI – A new study satellite tracked 17 young loggerhead turtles in the Atlantic Ocean to better understand sea turtle nursery grounds and early habitat use during the 'lost years.' The study, conducted by a collaborative research team, including scientists from the University of Miami (UM) Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, was the first long-term satellite tracking study of young turtles at sea.

"This is the first time we were able to show the maiden voyage of young turtles after they left the beach," said Rosenstiel School scientist Jiangang Luo ...

$4M grant to improve asthma care for So Cal Latino youth

2014-03-06

SAN DIEGO, Calif. (March 6, 2014)—A team led by researchers at San Diego State University has been awarded $4 million to enhance asthma education and treatment strategies in California's Imperial Valley, where children are twice as likely as the national average to suffer from asthma.

The grant will allow researchers to better understand the specific asthma needs of Imperial Valley's largely Latino/Latina population, as well as develop more effective approaches to treatment for families, communities, and physicians.

Approximately 4.5 million African-Americans and 3.6 ...

Fertilizer in small doses yields higher returns for less money

2014-03-06

URBANA, Ill. - Crop yields in the fragile semi-arid areas of Zimbabwe have been declining over time due to a decline in soil fertility resulting from mono-cropping, lack of fertilizer, and other factors. In collaboration with the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT), University of Illinois researchers evaluated the use of a precision farming technique called "microdosing," its effect on food security, and its ability to improve yield at a low cost to farmers.

"Microdosing involves applying a small, affordable amount of fertilizer ...

Story Tips from the Department of Energy's Oak Ridge National Laboratory, March 2014

2014-03-06

MATERIALS – Lighter, stronger engines . . .

Engines could become lighter and more efficient because of a research project that combines the talents and resources of the Chrysler Group, Nemak S.A. of Mexico and Oak Ridge National Laboratory. The goal of the four-year $5.5 million cooperative research and development agreement is to develop an advanced cast aluminum alloy for next-generation higher efficiency engines. In addition to being lighter, the new alloy for cylinder heads would be stronger and capable of sustaining the higher temperatures and pressures of engines ...

Preschoolers can outsmart college students at figuring out gizmos

2014-03-06

Preschoolers can be smarter than college students at figuring out how unusual toys and gadgets work because they're more flexible and less biased than adults in their ideas about cause and effect, according to new research from the University of California, Berkeley, and the University of Edinburgh.

The findings suggest that technology and innovation can benefit from the exploratory learning and probabilistic reasoning skills that come naturally to young children, many of whom are learning to use smartphones even before they can tie their shoelaces. The findings also ...

Kawasaki disease and pregnant women

2014-03-06

In the first study of its type, researchers at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine have looked at the health threat to pregnant women with a history of Kawasaki disease (KD), concluding that the risks are low with informed management and care.

The findings are published in the March 6, 2014 online edition of the British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology.

KD is a childhood condition affecting the coronary arteries. It is the most common cause of acquired heart disease in children. First recognized in Japan following World War II, KD diagnoses ...

Early detection helps manage a chronic graft-vs.-host disease complication

2014-03-06

SEATTLE – A simple questionnaire that rates breathing difficulties on a scale of 0 to 3 predicts survival in chronic graft-vs.-host disease, according to a study published in the March issue of Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation.

And although a poor score means a higher risk of death, asking a simple question that can spot lung involvement early means that patients can begin treatments to reduce or manage symptoms, said senior author Stephanie Lee, M.D., M.P.H., research director of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center's Long-Term Follow-Up Program, member ...