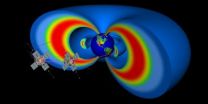

(Press-News.org) Using data from NASA's Van Allen Probes, researchers have tested and improved a model to help forecast what's happening in the radiation environment of near-Earth space -- a place seething with fast-moving particles and a space weather system that varies in response to incoming energy and particles from the sun.

When events in the two giant doughnuts of radiation around Earth – called the Van Allen radiation belts -- cause the belts to swell and electrons to accelerate to 99 percent the speed of light, nearby satellites can feel the effects. Scientists ultimately want to be able to predict these changes, which requires understanding of what causes them.

Now, two sets of related research published in the Geophysical Research Letters improve on these goals. By combining new data from the Van Allen Probes with a high-powered computer model, the new research provides a robust way to simulate events in the Van Allen belts.

"The Van Allen Probes are gathering great measurements, but they can't tell you what is happening everywhere at the same time," said Geoff Reeves, a space scientist at Los Alamos National Laboratory, or LANL, in Los Alamos, N.M., a co-author on both of the recent papers. "We need models to provide a context, to describe the whole system, based on the Van Allen Probe observations."

Prior to the launch of the Van Allen Probes in August 2012, there were no operating spacecraft designed to collect real-time information in the radiation belts. Understanding of what might be happening in any locale was forced to rely mainly on interpreting historical data, particularly those from the early 1990s gathered by the Combined Release and Radiation Effects Satellite, or CRRES.

Imagine if meteorologists wanted to predict the temperature on March 5, 2014, in Washington, D.C. but the only information available was from a handful of measurements made in March over the last seven years up and down the East Coast. That's not exactly enough information to decide whether or not you need to wear your hat and gloves on any given day in the nation's capital.

Thankfully, we have much more historical information, models that help us predict the weather and, of course, innumerable thermometers in any given city to measure temperature in real time. The Van Allen Probes are one step toward gathering more information about space weather in the radiation belts, but they do not have the ability to observe events everywhere at once. So scientists use the data they now have available to build computer simulations that fill in the gaps.

The recent work centers around using Van Allen Probes data to improve a three-dimensional model created by scientists at LANL, called DREAM3D, which stands for Dynamic Radiation Environment Assimilation Model in 3 Dimensions. Until now the model relied heavily on the averaged data from the CRRES mission.

One of the recent papers, published Feb. 7, 2014, provides a technique for gathering real-time global measurements of chorus waves, which are crucial in providing energy to electrons in the radiation belts. The team compared Van Allen Probes data of chorus wave behavior in the belts to data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Polar-orbiting Operational Environmental Satellites, or POES, flying below the belts at low altitude. Using this data and some other historical examples, they correlated the low-energy electrons falling out of the belts to what was happening directly in the belts.

"Once we established the relationship between the chorus waves and the precipitating electrons, we can use the POES satellite constellation – which has quite a few satellites orbiting Earth and get really good coverage of the electrons coming out of the belts," said Los Alamos scientist Yue Chen, first author of the chorus waves paper. "Combining that data with a few wave measurements from a single satellite, we can remotely sense what's happening with the chorus waves throughout the whole belt."

The relationship between the precipitating electrons and the chorus waves does not have a one-to-one precision, but it does provide a much narrower range of possibilities for what's happening in the belts. In the metaphor of trying to find the temperature for Washington on March 5, it's as if you still didn't have a thermometer in the city itself, but can make a better estimate of the temperature because you have measurements of the dewpoint and humidity in a nearby suburb.

The second paper describes a process of augmenting the DREAM3D model with data from the chorus wave technique, from the Van Allen Probes, and from NASA's Advanced Composition Explorer, or ACE, which measures particles from the solar wind. Los Alamos researchers compared simulations from their model – which now was able to incorporate real-time information for the first time – to a solar storm from October 2012.

"This was a remarkable and dynamic storm," said lead author Weichao Tu at Los Alamos. "Activity peaked twice over the course of the storm. The first time the fast electrons were completely wiped out – it was a fast drop out. The second time many electrons were accelerated substantially. There were a thousand times more high-energy electrons within a few hours."

Tu and her team ran the DREAM3D model using the chorus wave information and by including observations from the Van Allen Probes and ACE. The scientists found that their computer simulation made by their model recreated an event very similar to the October 2012 storm.

What's more the model helped explain the different effects of the different peaks. During the first peak, there simply were fewer electrons around to be accelerated.

However, during the early parts of the storm the solar wind funneled electrons into the belts. So, during the second peak, there were more electrons to accelerate.

"That gives us some confidence in our model," said Reeves. "And, more importantly, it gives us confidence that we are starting to understand what's going on in the radiation belts."

INFORMATION:

The Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Md., built and operates the probes for NASA's Science Mission Directorate. The Van Allen Probes are the second mission in NASA's Living With a Star program, managed by NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. The research was jointly supported by LANL's Laboratory Directed Research and Development program and the University of California's Laboratory Fee Research Program. The DREAM3D model is run using LANL's high performance computing.

For more on the Van Allen Probes, visit:

http://www.nasa.gov/vanallen

New NASA Van Allen Probes observations helping to improve space weather models

2014-03-07

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

NASA satellites see double tropical trouble for Queensland, Australia

2014-03-07

There are two developing areas of tropical low pressure that lie east and west of Queensland, Australia. System 96P and System 98P, respectively. The MODIS instrument that flies aboard both NASA's Aqua and Terra satellites captured images of both tropical trouble-makers as each satellite passed overhead on March 7.

In the Coral Sea, part of the Southwestern Pacific Ocean, System 96P was just 125 nautical miles/143.8 miles/231.5 km north-northeast of Willis Island, Australia. It was centered near 14.3 south latitude and 150.6 east longitude. System 96P is moving in south-southwesterly ...

The dark side of fair play

2014-03-07

We often think of playing fair as an altruistic behavior. We're sacrificing our own potential gain to give others what they deserve. What could be more selfless than that? But new research from Northeastern University assistant professor of philosophy Rory Smead suggests another, darker origin behind the kindly act of fairness.

Smead studies spite. It's a conundrum that evolutionary biologists and behavioral philosophers have been mulling over for decades, and it's still relatively unclear why the seemingly pointless behavior sticks around. Technically ...

Service is key to winery sales

2014-03-07

ITHACA, N.Y. – To buy, or not to buy? That is the question for the more than 5 million annual visitors to New York's wineries. Cornell University researchers found that customer service is the most important factor in boosting tasting room sales, but sensory descriptions of what flavors consumers might detect were a turn-off.

The findings stem from two studies on how the tasting room experience affects customer purchases and what wineries can do to create satisfied sippers, published in the current issue of the International Journal of Wine Business Research.

"On average, ...

Ever-so-slight delay improves decision-making accuracy

2014-03-07

NEW YORK, NY (March 7, 2014) — Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC) researchers have found that decision-making accuracy can be improved by postponing the onset of a decision by a mere fraction of a second. The results could further our understanding of neuropsychiatric conditions characterized by abnormalities in cognitive function and lead to new training strategies to improve decision-making in high-stake environments. The study was published in the March 5 online issue of the journal PLoS One.

"Decision making isn't always easy, and sometimes we make errors ...

Notre Dame chemists discover new class of antibiotics

2014-03-07

A team of University of Notre Dame researchers led by Mayland Chang and Shahriar Mobashery have discovered a new class of antibiotics to fight bacteria such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and other drug-resistant bacteria that threaten public health. Their research is published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society in an article titled "Discovery of a New Class of Non-beta-lactam Inhibitors of Penicillin-Binding Proteins with Gram-Positive Antibacterial Activity."

The new class, called oxadiazoles, was discovered in silico (by computer) ...

New theory on cause of endometriosis

2014-03-07

Changes to two previously unstudied genes are the centerpiece of a new theory regarding the cause and development of endometriosis, a chronic and painful disease affecting 1 in 10 women.

The discovery by Northwestern Medicine scientists suggests epigenetic modification, a process that enhances or disrupts how DNA is read, is an integral component of the disease and its progression. Matthew Dyson, research assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine and and Serdar Bulun, MD, chair of obstetrics and gynecology ...

Bone turnover markers predict prostate cancer outcomes

2014-03-07

(SACRAMENTO, Calif.) —Biomarkers for bone formation and resorption predict outcomes for men with castration-resistant prostate cancer, a team of researchers from UC Davis and their collaborators have found. Their study, published online in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute, also found that the markers identified a small group of patients who responded to the investigational drug atrasentan. The markers' predictive ability could help clinicians match treatments with individual patients, track their effectiveness and affect clinical trial design.

Castration-resistant ...

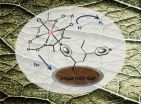

Promising news for solar fuels from Berkeley Lab researchers at JCAP

2014-03-07

There's promising news from the front on efforts to produce fuels through artificial photosynthesis. A new study by Berkeley Lab researchers at the Joint Center for Artificial Photosynthesis (JCAP) shows that nearly 90-percent of the electrons generated by a hybrid material designed to store solar energy in hydrogen are being stored in the target hydrogen molecules.

Gary Moore, a chemist and principal investigator with Berkeley Lab's Physical Biosciences Division, led an efficiency analysis study of a unique photocathode material he and his research group have developed ...

Anti-psychotic medications offer new hope in the battle against glioblastoma

2014-03-07

Researchers at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine have discovered that FDA-approved anti-psychotic drugs possess tumor-killing activity against the most aggressive form of primary brain cancer, glioblastoma. The finding was published in this week's online edition of Oncotarget.

The team of scientists, led by principal investigator, Clark C. Chen, MD, PhD, vice-chairman, UC San Diego, School of Medicine, division of neurosurgery, used a technology platform called shRNA to test how each gene in the human genome contributed to glioblastoma growth. ...

Agricultural fires across the Indochina landscape

2014-03-07

Agricultural fires are still burning in Indochina ten days after the last NASA web posting about the fires. This natural-color image, taken on March 07, 2014, by the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer, MODIS, aboard the Aqua satellite, shows a more comprehensive area of burning agricultural fires that stretch from Burma through to Laos and south throughout Thailand. Actively burning areas, detected by MODIS's thermal bands, are outlined in red.Fire is used in cropland areas for pest and weed control and to prepare fields for planting. Crop residue burning helps ...