(Press-News.org) EAST LANSING, Mich. — Imitation is the most sincere form of flattery – especially in the predator/prey/poison cycle.

In nature, bright colors are basically neon signs that scream, "Don't eat me!" But how did prey evolve these characteristics? When did predators translate the meaning?

In the current issue of the journal PLOS ONE, researchers at Michigan State University reveal that these color-coded communiqués evolve over time through gradual steps. Equally interesting, the scientists show how drab-colored, oft-eaten prey adopt garish colors to live long and prosper, even though they aren't poisonous, said Kenna Lehmann, MSU doctoral student of zoology.

"In some cases, nonpoisonous prey gave up their protection of camouflage and acquired bright colors," said Lehmann, who conducted the research through MSU's BEACON Center for the Study of Evolution in Action. "How did these imitators get past that tricky middle ground, where they can be easily seen, but they don't quite resemble colorful toxic prey? And why take the risk?"

They take the risk because the evolutionary benefit of mimicry works. A nontoxic imposter benefits from giving off a poisonous persona, even when the signals are not even close. Predators, engrained to avoid truly toxic prey, react to the impersonations and avoid eating the imposters.

An example of truly toxic animals and their imitators are coral snakes and king snakes. While coral snakes are poisonous, king snakes are not. Even though king snakes are considered imperfect mimics, they are close enough that predators don't bother them.

Why don't all prey have these characteristics, and why don't the imitators evolve to develop poison instead? Leaving the safety of the cryptic, camouflage peak to go through the exposed adaptive valley over many generations is a dangerous journey, Lehmann said.

"To take the risk of traversing the dangerous middle ground – where they don't look enough like toxic prey – is too great in many cases," she said. "Toxins can be costly to produce. If prey gain protection by colors alone, then it doesn't make evolutionary sense to expend additional energy developing the poison."

The results suggest that these communicative systems can evolve through gradual steps instead of an unlikely large single step. This gives insight into how complex signals, both sent and received, may have evolved through seemingly disadvantageous steps.

Rather than conduct experiments of voracious predators chasing and eating, or completely avoiding, prey, the scientists used evolving populations of digital organisms in a virtual world called Avida.

Avida is a software environment developed at MSU in which specialized computer programs compete and reproduce. Because mutations happen when Avidians copy themselves, which lead to differences in reproductive rates, these digital organisms evolve, just like living things.

INFORMATION:

Additional MSU scientists who contributed to the study include: Brian Goldman, Ian Dworkin, David Bryson and Aaron Wagner.

This research was funded by the National Science Foundation.

Michigan State University has been working to advance the common good in uncommon ways for more than 150 years. One of the top research universities in the world, MSU focuses its vast resources on creating solutions to some of the world's most pressing challenges, while providing life-changing opportunities to a diverse and inclusive academic community through more than 200 programs of study in 17 degree-granting colleges.

For MSU news on the Web, go to MSUToday. Follow MSU News on Twitter at twitter.com/MSUnews.

Impersonating poisonous prey

2014-03-10

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Claim that raw milk reduces lactose intolerance doesn't pass smell test, study finds

2014-03-10

STANFORD, Calif. — Some sour news for lactose-intolerant people who hoped that raw milk might prove easier to stomach than pasteurized milk: A pilot study from the Stanford University School of Medicine shows little difference in digestibility between the two.

The study was small — it involved 16 participants — but the lead investigator said the results were highly consistent among all the participants and deflate some of the claims surrounding raw, or unpasteurized, milk.

"It's not that there was a trend toward a benefit from raw milk and our study wasn't big enough ...

Small biomass power plants could help rural economies, stabilize national power grid, MU study finds

2014-03-10

COLUMBIA, Mo. – As energy costs rise, more Americans are turning to bioenergy to provide power to their homes and workplaces. Bioenergy is renewable energy made from organic sources, such as biomass. Technology has advanced enough that biomass power plants small enough to fit on a farm can be built at relatively low costs. Now, University of Missouri researchers have found that creating a bioenergy grid with these small plants could benefit people in rural areas of the country as well as provide relief to an overworked national power grid.

"Transporting power through ...

UV light aids cancer cells that creep along the outside of blood vessels

2014-03-10

A new study by UCLA scientists and colleagues adds further proof to earlier findings by Dr. Claire Lugassy and Dr. Raymond Barnhill of UCLA's Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center that deadly melanoma cells can spread through the body by creeping like tiny spiders along the outside of blood vessels without ever entering the bloodstream.

In addition, the new research, published March 6 in the journal Nature, demonstrates that this process is accelerated when the skin cancer cells are exposed to ultraviolet light. The husband-and-wife team of Barnhill and Lugassy collaborated ...

Natural selection has altered the appearance of Europeans over the past 5,000 years

2014-03-10

There has been much research into the factors that have influenced the human genome since the end of the last Ice Age. Anthropologists at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU) and geneticists at University College London (UCL), working in collaboration with archaeologists from Berlin and Kiev, have analyzed ancient DNA from skeletons and found that selection has had a significant effect on the human genome even in the past 5,000 years, resulting in sustained changes to the appearance of people. The results of this current research project have been published this week ...

JCI online ahead of print table of contents for March 10, 2014

2014-03-10

Identification of a broadly neutralizing HIV-1 antibody in a lupus patient

Broadly neutralizing antibodies (BnAbs) recognize conserved epitopes, representing a promising strategy for targeting rapidly mutating viruses. BnAbs display a unique set of characteristics that suggest their development may be limited by immune tolerance. Interestingly, the HIV-1 infection frequency is disproportionately low among patients with the autoimmune disease lupus. In this issue of the Journal of Clinical Investigation, Mattia Bonsignori and colleagues at Duke University identified an ...

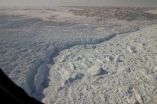

NASA data shed new light on changing Greenland ice

2014-03-10

Research using NASA data is giving new insight into one of the processes causing Greenland's ice sheet to lose mass. A team of scientists used satellite observations and ice thickness measurements gathered by NASA's Operation IceBridge to calculate the rate at which ice flows through Greenland's glaciers into the ocean. The findings of this research give a clearer picture of how glacier flow affects the Greenland Ice Sheet and shows that this dynamic process is dominated by a small number of glaciers.

Over the past few years, Operation IceBridge measured the thickness ...

Shade will be a precious resource to lizards in a warming world

2014-03-10

Climate change may even test lizards' famous ability to tolerate and escape the heat -- making habitat protection increasingly vital -- according to a new study by UBC and international biodiversity experts.

The study, published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, looks at the heat and cold tolerance of 296 species of reptiles, insects and amphibians, known as ectotherms. The researchers discovered that regardless of latitude or elevation, cold-blooded animals across the world have similar heat tolerance limits. However, species in the tropics ...

A tale of 2 data sets: New DNA analysis strategy helps researchers cut through the dirt

2014-03-10

For soil microbiology, it is the best of times. While no one has undertaken an accurate census, a spoonful of soil holds hundreds of billions of microbial cells, encompassing thousands of species. "It's one of the most diverse microbial habitats on Earth, yet we know surprisingly little about the identities and functions of the microbes inhabiting soil," said Jim Tiedje, Distinguished Professor at the Center for Microbial Ecology at Michigan State University. Tiedje, along with MSU colleagues and collaborators from the U.S. Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute (DOE ...

Mecasermin (rh-IGF-1) treatment for Rett Syndrome is safe and well-tolerated

2014-03-10

(Cincinnati, OH) – The results from Boston Children's Hospital's Phase 1 human clinical trial in Rett syndrome came out today. A team of investigators successfully completed a Phase 1 clinical trial using mecasermin [recombinant human insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1)], showing proof-of-principle that treatments like IGF-1 which are based on the neurobiology of Rett syndrome, are possible. The study deemed that IGF-1 is safe and well tolerated in girls diagnosed with Rett syndrome, and the data also suggests that certain breathing and behavioral symptoms associated ...

National study reveals urban lawn care habits

2014-03-10

(Millbrook, NY) What do people living in Boston, Baltimore, Miami, Minneapolis-St. Paul, Phoenix, and Los Angeles have in common? From coast to coast, prairie to desert – residential lawns reign.

But, according to a new study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, beneath this sea of green lie unexpected differences in fertilization and irrigation practices. Understanding urban lawn care is vital to sustainability planning, more than 80% of Americans live in cities and their suburbs, and these numbers continue to grow.

The study was undertaken to ...