(Press-News.org) VIDEO:

One puppet peeks at another puppet's drawing because he can't decide what to draw, but he then draws a unique picture.

Click here for more information.

Even very young children understand what it means to steal a physical object, yet it appears to take them another couple of years to understand what it means to steal an idea.

University of Washington psychologist Kristina Olson and colleagues from Yale and the University of Pennsylvania discovered that preschoolers often don't view a copycat negatively, but they do by the age of 5 or 6. And that holds true even across cultures that typically view intellectual property rights in different ways.

"Physical property is something that can be seen, but intellectual property is something that can't be seen, and it's hard to understand, let alone place a value on that," Olson said. "So it's not surprising that it's so hard for younger kids to understand intellectual property rights."

The results are published in the Journal of Experimental Child Psychology.

The researchers wanted to know whether young children in different cultures placed more value on unique artwork or copies of someone else's work. They evaluated 3- to 6-year-old children in the United States, Mexico and China – chosen by the researchers based on the different emphasis each country places on the protection of intellectual property and ideas.

Researchers had children watch videos of puppets producing a unique drawing or plagiarizing another character's drawing. The videos were in the children's native language (English, Mandarin or Spanish).

Each child watched three 30-second videos. At the beginning of each video, one puppet looked at what the other puppet was drawing. In one video, the puppet that peeked then created an identical drawing. In the second video, he created a similar drawing with the same theme but different colors and shape elements. In the third, the puppet that looked at the other's drawing drew a completely different picture.

After watching each video, the children rated how good or bad the puppets were.

Five- and 6-year-olds from all three cultures rated the puppet who copied the others' work negatively. However, 3- and 4-year-olds evaluated plagiarism much differently than the older children, as well as differently across cultures. Mexican preschoolers rated unique drawers more positively than the plagiarizers, but, American and Chinese 3- and 4-year-olds didn't distinguish much between characters who created original drawings and plagiarized ones. And Chinese preschoolers rated copycats more positively than those who drew something similar.

"Sometimes copying is good; for example, when we learn to write, we all learn this is how you make an A, so that's not considered plagiarism," Olson said. "That may be confusing to children, because sometimes we tell them to come up with novel ideas but other times they're supposed to copy. It's interesting to think about how kids are sorting that out."

The researchers chose to study children in the U.S., which has strong protections in place for intellectual property, and China, which did not until very recently (establishing its first patent law in 1984, more than 150 years after the U.S. and most of Europe). They also chose Mexico because it is in the middle of the spectrum in protecting intellectual property.

"This is a nice example of how we often think there are huge differences across cultures and that a lot of everyday judgments are colored by our culture. But, this study shows that even in very different cultures, the underlying psychology is sometimes quite similar," Olson said. "By age 5 or 6 across all of these cultures you find that kids think being a copycat is bad."

INFORMATION:

Co-authors of the study are Fan Yang, a graduate student at the University of Pennsylvania, and Alex Shaw and Eric Garduno, formerly students at Yale. Olson conducted the research while at Yale University; she joined the University of Washington in summer 2013.

Olson can be reached at krolson@uw.edu or 206-616-1371.

No one likes a copycat, no matter where you live

2014-03-11

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Global survey of urban birds and plants find more diversity than expected

2014-03-11

AMHERST, Mass. – The largest analysis to date of the effect of urbanization on bird and plant species diversity worldwide confirms that while human influences such as land cover are more important drivers of species diversity in cities than geography or climate, many cities retain high numbers of native species and are far from barren environments.

Urban ecologist Paige Warren of the University of Massachusetts Amherst, co-leader of a 24-member research working group at the University of California Santa Barbara's National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis ...

Diets high in animal protein may help prevent functional decline in elderly individuals

2014-03-11

A diet high in protein, particularly animal protein, may help elderly individuals function at higher levels physically, psychologically, and socially, according to a study published in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society.

Due to increasing life expectancies in many countries, increasing numbers of elderly people are living with functional decline, such as declines in cognitive ability and activities of daily living. Functional decline can have profound effects on health and the economy.

Research suggests that aging may reduce the body's ability to absorb or ...

Substance naturally found in humans is effective in fighting brain damage from stroke

2014-03-11

DETROIT – A molecular substance that occurs naturally in humans and rats was found to "substantially reduce" brain damage after an acute stroke and contribute to a better recovery, according to a newly released animal study by researchers at Henry Ford Hospital.

The study, published online before print in Stroke, the journal of the American Heart Association, was the first ever to show that the peptide AcSDKP provides neurological protection when administered one to four hours after the onset of an ischemic stroke.

This type of a stroke occurs when an artery to the brain ...

NASA eyes 2 tropical cyclones east of Australia

2014-03-11

NASA's Aqua and TRMM satellites have been providing rainfall data, cloud heights and temperature and other valuable information to forecasters at the Joint Typhoon Warning Center as they track Tropical Cyclones Hadi and Lusi in the South Pacific.

NASA's Aqua satellite captured both storms in one infrared image on March 10 at 14:47 UTC/10:47 a.m. EST. At that time, Hadi was near the east Queensland coast while Lusi was several hundred miles north of New Caledonia. The Atmospheric Infrared Sounder or AIRS instrument captured infrared data that was used to create a false-colored ...

Alps to Appalachia; submarine channels to Tibetan plateau; Death Valley to arctic Canada

2014-03-11

Boulder, Colo., USA – On 27 Feb. and 6 Mar. 2014, GSA Bulletin published 11 articles online ahead of print, including two that are open access: "O2 constraints from Paleoproterozoic detrital pyrite and uraninite" and "Sediment transfer and deposition in slope channels: Deciphering the record of enigmatic deep-sea processes from outcrop." Other articles cover geological features in the Alps; the Appalachians; Death Valley; India; the Himalaya; the Columbia River Basalt Province; San Simeon, California; Kaua'i, Hawai'i; and artic Canada.

GSA Bulletin articles published ...

Scientists from Penn and CHOP confirm link between missing DNA and birth defects

2014-03-11

In 2010, scientists in Italy reported that a woman and her daughter showed a puzzling array of disabilities, including epilepsy and cleft palate. The mother had previously lost a 15-day-old son to respiratory failure, and the research team noted that the mother and daughter were missing a large chunk of DNA on their X chromosome. But the researchers were unable to definitively show that the problems were tied to that genetic deletion.

Now a team from the University of Pennsylvania and The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia has confirmed that those patients' ailments ...

Lessons learned managing geriatric patients offer framework for improved care

2014-03-11

A large team of experts led by a Johns Hopkins geriatrician reports that efforts to improve the care of older adults and others with complex medical needs will fall short unless public policymakers focus not only on preventing hospital readmission rates, but also on better coordination of community-based "care transitions." Lessons learned from managing such transitions for older patients, they say, may offer a framework for overall improvement.

Nationwide, some 22 percent of older adults experience so-called care transitions annually, moving from and among hospitals, ...

Change happens: New maps reveal land cover change over 5 years across North America

2014-03-11

This news release is available in French and Spanish. Montreal, 11 March 2014—A new set of maps featured in the CEC's North American Environmental Atlas depicts land cover changes in North America's forests, prairies, deserts and cities, using satellite images from 2005 and 2010. These changes can be attributed to forest fires, insect infestation, urban sprawl and other natural or human-caused events. Produced by the North American Land Change Monitoring System (NALCMS), a trinational collaborative effort facilitated by the CEC, these maps and accompanying data can ...

AGU journal highlights -- March 11, 2014

2014-03-11

The following highlights summarize research papers that have been recently published in Geophysical Research Letters (GRL), Journal of Geophysical Research-Atmospheres (JGR-D), and Journal of Geophysical Research-Earth Surface (JGR-F).

In this release:

Cassini sheds light on Titan's second largest lake, Ligeia Mare

Tectonic stress feedback loop explains U-shaped glacial valleys

Measuring the effect of water vapor on climate warming

First assessment of noctilucent cloud variability at midlatitudes

Modeling surface circulation patterns in the Gulf of Mexico

New ...

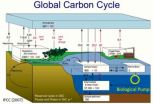

Ocean food web is key in the global carbon cycle

2014-03-11

(Santa Barbara, Calif.) — Nothing dies of old age in the ocean. Everything gets

eaten and all that remains of anything is waste. But that waste is pure gold to

oceanographer David Siegel, director of the Earth Research Institute at UC Santa

Barbara.

In a study of the ocean's role in the global carbon cycle, Siegel and his colleagues used those nuggets to their advantage. They incorporated the lifecycle of phytoplankton

and zooplankton — small, often microscopic animals at the bottom of the food chain —into a novel mechanistic model for assessing the global ocean carbon ...