(Press-News.org) This news release is available in German.

Chemical reactions taking place in outer space can now be more easily studied on Earth. An international team of researchers from the University of Aarhus in Denmark and the Max Planck Institute for Nuclear Physics in Heidelberg, discovered an efficient and versatile way of braking the rotation of molecular ions. The spinning speed of these ions is related to a rotational temperature. Using an extremely tenuous, cooled gas, the researchers have lowered this temperature to about -265 °C. From this record-low value, the researchers could vary the temperature up to -210 °C in a controlled manner. Exact control of the rotation of molecules is not only of importance for studying astrochemical processes, but could also be exploited to shed more light on the quantum mechanical aspects of photosynthesis or to use molecular ions for quantum information technology.

Cold does not equal cold for physicists. This is because in physics, there is a different temperature associated with each type of motion that a particle can have. How fast molecules move through space determines the translational temperature, which comes closest to our everyday notion of temperature.

However, there is also a temperature for the internal vibrations of a molecule, as well as for the rotational motion around their own axes. Similar to a stationary car with its engine running, the internal rotation (the engine, in this case) does not translate into motion before the clutch is released. In the case of molecules, the many microscopic collisions between the particles which constitute gases, fluids, and solids couple the various forms of motion with each other.

The different temperatures thus approach each other over time. Physicists then say that a thermal equilibrium has been established. However, how fast this equilibrium is reached depends on the collision rate, as well as on any external influences working against this equilibration. For example, the infrared radiation emanating from the contraction of an interstellar gas cloud can cause the rotation of molecules to quicken, even without changing the speed at which the molecules are travelling. These kinds of processes take a very long time in the emptiness of space, as there are very few collisions there.

The cooling method for the rotational temperature is quick and versatile

Time is totally irrelevant at cosmic dimensions but with physical experiments it is crucial. Indeed, physicists can nowadays reduce the flight speed of molecules relatively quickly to almost absolute zero at -273.15 °C. However, it takes several minutes or hours for the rotation of non-colliding particles to cool to a similar level, making some experiments almost impossible. This may be about to change.

"We have managed to cool down the rotation of molecular ions in milliseconds, and down to lower temperatures than previously possible," says José R. Crespo López-Urrutia, Group Leader at the Max Planck Institute for Nuclear Physics. The researchers from the Max Planck Institute in Heidelberg and the group led by Michael Drewsen at Aarhus University froze molecular rotational motion at 7.5 K (or -265.65 °C). And not only that, as Oscar Versolato from the Max Planck Institute in Heidelberg, who played an important role in the experiments, explains: "With our methods we can choose and set a rotational temperature between about seven and 60 Kelvin, and are able to accurately measure this temperature in our experiments." Unlike other methods, this cooling principle is very versatile, being applicable to many different molecular ions.

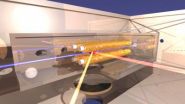

In their experiments, the team used a cloud of magnesium ions and magnesium hydride ions using methods pioneered in Aarhus. This ensemble was "confined" in an ion trap known as CryPTEx, which was developed by researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Nuclear Physics (see Background). The trap consists of four rod-shaped electrodes that are arranged in parallel, in pairs aligned one above the other and having opposite electrical polarities. A high-frequency alternating voltage is applied to the electrodes to confine the ions in the centre close to the longitudinal axis of the trap. The trap is cooled to a few degrees above absolute zero, and there is an excellent vacuum so that adverse collisions are very rare.

Collisions with cold helium atoms slow down the rotation of the molecular ions

In the trap, the physicists cooled the magnesium ions using laser beams which, to put it simply, slow down the ions with their photon pressure. The magnesium hydride ions in turn cool because of their interaction with the magnesium ions. This allowed the researchers to cool the translational temperature of the cloud to minus 273 degrees Celsius until several hundred particles solidify to form a regular crystal. In such crystals, the distances between the particles are very large, in contrast to the situation in crystals familiar from minerals. The particles which the cold laser causes to emit light can thus be seen at their fixed positions under the optical microscope.

To apply a brake to the rotation of the molecular ions, and thus to reduce their rotational temperature, the team injected an extremely tenuous, cold helium gas into the trap. In the ion crystal, the helium atoms flying at a leisurely speed collide with the magnesium hydride ions rotating about their own axis trillions of times per second. The collisions cause the helium atoms to gradually slow down the molecular ions. "This process is similar to the tides," explains José Crespo: "The rotating ion polarizing the neutral helium atom is a little bit like the moon producing the tidal bulges." A dipole is thus induced in the helium atom, which tugs at the rotating molecular ion such that it rotates a little slower.

The helium atoms in the experiment mediate between the various temperatures as they transfer translational kinetic energy to the molecular ions in some collisions and remove rotational energy in others. This effect is also exploited by the team to heat the rotational motion of the molecular ions through the amplification of the regular micro-motion of trapped particles.

Crystal size and shape control the heating of molecular ions

The physicists increase the micro-motion velocity of the molecular ions by varying the shape and size of the ion crystal in the trap: they knead the crystal as it were by means of the alternating voltage which is applied to the trap electrodes. The alternating field that the electrodes produce is equal to zero only along the trap axis. The further the molecular ions are located away from this axis, the more they feel the oscillating force of the field and the more violent is their micro-motion. Part of the kinetic energy of the swirling molecular ions is absorbed by the helium atoms in collisions, and these atoms in turn transfer it to the rotational motion of the ions, thus raising their rotational temperature.

For the Danish-German collaboration, the ability to control the rotation of the molecular ions not only enables the manipulation of the micro-motion, and thus the rotational temperature, but also the quantum-mechanical measurement of this temperature. The scientists do this by exploiting the fact that the rotational motion of the molecules is quantised. Put simply: the quantum states of a molecule correspond to certain speeds of its rotation.

At very cold temperatures the molecules occupy only very few quantum states. The researchers remove the molecules of one quantum state from the crystal by means of laser pulses whose energy is matched to that particular state. They determine how many ions are lost in this process, in other words how many ions take on this particular quantum state, from the size of the crystal remaining. They determine the rotational temperature of the molecular ions by thus scanning a few quantum states.

Accurate control of quantum states is a prerequisite for many experiments

"Being able to control the rotation of the molecular ions and thus the quantum state so accurately is important for many experiments," says José Crespo.

Scientists can therefore recreate in the laboratory chemical reactions that take place in space if they can bring the reactants into the same quantum state in which they drift through interstellar space. Only in this way can one quantitatively understand how molecules are formed in space, and ultimately explain how interstellar clouds, the hotbeds of stars and planets, evolve both physically and chemically.

This speed control knob for rotating molecules could also contribute to a better understanding of the quantum physics of photosynthesis. In photosynthesis, plants use the chlorophyll in their leaves to collect sunlight, whose energy is ultimately used to form sugars and other molecules. It is not yet entirely clear how the energy required for this is quantum mechanically transferred within the chlorophyll molecules. To understand this, the researchers must once again very accurately control and measure the quantum states and the rotation of the molecules involved. The findings thus obtained could serve as the basis for imitating or optimising the photosynthesis at some time in the future in order to supply us with energy.

Last but not least, this control is a prerequisite for quantum simulations as well as for many concepts of universal quantum computations. In quantum simulations physicists mimic a quantum mechanical system that is difficult, or even impossible, to examine directly with another quantum system that is well-known and controllable. In universal quantum computers which physicists are trying to develop, the aim is to process information extremely quickly using the quantum states of particles. Molecules are possible candidates for this, their chances now growing as molecular rotation can be quantum mechanically controlled.

"Our method for the cooling of the rotation of molecules opens up new possibilities in a variety of different fields," says José Crespo. His team, too, will now use the new method to investigate open questions about the quantum mechanical world.

INFORMATION:

Anders K. Hansen, Oscar O. Versolato, Lukasz Klosowski, Simon B. Kristensen, Alexander D. Gingell, Maria Schwarz, Alexander Windberger, Joachim Ullrich, José R. Crespo López-Urrutia & Michael Drewsen

Efficient rotational cooling of Coulomb-crystallized molecular ions by a helium buffer gas

Nature, advance online publication 9 March 2014; doi: 10.1038/nature12996

A brake for spinning molecules

The precise control of the rotational temperature of molecular ions opens up new possibilities for laboratory-based astrochemistry

2014-03-13

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Soft robotic fish moves like the real thing

2014-03-13

Soft robots — which don't just have soft exteriors but are also powered by fluid flowing through flexible channels — have become a sufficiently popular research topic that they now have their own journal, Soft Robotics. In the first issue of that journal, out this month, MIT researchers report the first self-contained autonomous soft robot capable of rapid body motion: a "fish" that can execute an escape maneuver, convulsing its body to change direction in just a fraction of a second, or almost as quickly as a real fish can.

"We're excited about soft robots for a variety ...

Heritable variation discovered in trout behavior

2014-03-13

Populations of endangered salmonids are supported by releasing large quantities of hatchery-reared fish, but the fisheries' catches have continued to decrease. Earlier research has shown that certain behavioural traits explain individual differences in how fish survive in the wild. A new Finnish study conducted on brown trout now shows that there are predictable individual differences in behavioural traits, like activity, tendency to explore new surroundings and stress tolerance. Furthermore, certain individual differences were observed to contain heritable components. ...

3D X-ray film: Rapid movements in real time

2014-03-13

This news release is available in German. How does the hip joint of a crawling weevil move? A technique to record 3D X-ray films showing the internal movement dynamics in a spatially precise manner and, at the same time, in the temporal dimension has now been developed by researchers at ANKA, KIT's Synchrotron Radiation Source. The scientists applied this technique to a living weevil. From up to 100,000 two-dimensional radiographs per second, they generated complete 3D film sequences in real time or slow motion. The results are now published in the Proceedings of the ...

Standardized evaluation consent forms for living liver donors needed

2014-03-13

New research reveals that 57% of liver transplant centers use living donor evaluation consent forms that include all the elements required by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and 78% of centers addressed two-third or more of the items recommended by the Organ Procurement and Transplant Network (OPTN). The study published in Liver Transplantation, a journal of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the International Liver Transplantation Society, reviewed the living donor evaluation consent forms from 26 of the 37 transplant centers ...

Tropical grassy ecosystems under threat, scientists warn

2014-03-13

Scientists at the University of Liverpool have found that tropical grassy areas, which play a critical role in the world's ecology, are under threat as a result of ineffective management.

According to research, published in Trends in Ecology and Evolution, they are often misclassified and this leads to degradation of the land which has a detrimental effect on the plants and animals that are indigenous to these areas.

Tropical grassy areas cover a greater area than tropical rain forests, support about one fifth of the world's population and are critically important ...

Gene variants protect against relapse after treatment for hepatitis C

2014-03-13

More than 100 million humans around the world are infected with hepatitis C virus. The infection gives rise to chronic liver inflammation, which may result in reduced liver function, liver cirrhosis and liver cancer. Even though anti-viral medications often efficiently eliminate the virus, the infection recurs in approximately one fifth of the patients.

Prevents incorporation in DNA

Martin Lagging and co-workers at the Sahlgrenska Academy have studied an enzyme called inosine trifosfatas (ITPase), which normally prevents the incorporation of defective building blocks ...

Study: Response to emotional stress may be linked to some women's heart artery dysfunction

2014-03-13

LOS ANGELES (March 12, 2014) – Researchers at the Barbra Streisand Women's Heart Center at the Cedars-Sinai Heart Institute have found that emotional stressors – such as those provoking anger – may cause changes in the nervous system that controls heart rate and trigger a type of coronary artery dysfunction that occurs more frequently in women than men.

They will describe their findings at the American Psychosomatic Society's annual meeting on March 13 in San Francisco.

In men with coronary artery disease, the large arteries feeding the heart tend to become clogged ...

Most of the sand in Alberta's oilsands came from eastern North America, study shows

2014-03-13

They're called the Alberta oilsands but most of the sand actually came from the Appalachian region on the eastern side of the North American continent, a new University of Calgary-led study shows.

The oilsands also include sand from the Canadian Shield in northern and east-central Canada and from the Canadian Rockies in western Canada, the study says.

This study is the first to determine the age of individual sediment grains in the oilsands and assess their origin.

"The oilsands are looked at as a Western asset," says study lead author Christine Benyon, who is just ...

What happened when? How the brain stores memories by time

2014-03-13

VIDEO:

An area of the brain called the hippocampus stores memories based on their sequence in time, instead of by their content, UC Davis researchers have found. The discovery has implications...

Click here for more information.

Before I left the house this morning, I let the cat out and started the dishwasher. Or was that yesterday? Very often, our memories must distinguish not just what happened and where, but when an event occurred — and what came before and after. New research ...

A brain signal for psychosis risk

2014-03-13

Philadelphia, PA, March 13, 2014 – Only one third of individuals identified as being at clinical high risk for psychosis actually convert to a psychotic disorder within a 3 year follow-up period. This risk assessment is based on the presence of sub-threshold psychotic-like symptoms.

Thus, clinical symptom criteria alone do not predict future psychosis risk with sufficient accuracy to justify aggressive early intervention, especially with medications such as antipsychotics that produce significant side effects.

Accordingly, there is a strong imperative to develop biomarkers ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

ASU researchers to lead AAAS panel on water insecurity in the United States

ASU professor Anne Stone to present at AAAS Conference in Phoenix on ancient origins of modern disease

Proposals for exploring viruses and skin as the next experimental quantum frontiers share US$30,000 science award

ASU researchers showcase scalable tech solutions for older adults living alone with cognitive decline at AAAS 2026

Scientists identify smooth regional trends in fruit fly survival strategies

Antipathy toward snakes? Your parents likely talked you into that at an early age

Sylvester Cancer Tip Sheet for Feb. 2026

Online exposure to medical misinformation concentrated among older adults

Telehealth improves access to genetic services for adult survivors of childhood cancers

Outdated mortality benchmarks risk missing early signs of famine and delay recognizing mass starvation

Newly discovered bacterium converts carbon dioxide into chemicals using electricity

Flipping and reversing mini-proteins could improve disease treatment

Scientists reveal major hidden source of atmospheric nitrogen pollution in fragile lake basin

Biochar emerges as a powerful tool for soil carbon neutrality and climate mitigation

Tiny cell messengers show big promise for safer protein and gene delivery

AMS releases statement regarding the decision to rescind EPA’s 2009 Endangerment Finding

Parents’ alcohol and drug use influences their children’s consumption, research shows

Modular assembly of chiral nitrogen-bridged rings achieved by palladium-catalyzed diastereoselective and enantioselective cascade cyclization reactions

Promoting civic engagement

AMS Science Preview: Hurricane slowdown, school snow days

Deforestation in the Amazon raises the surface temperature by 3 °C during the dry season

Model more accurately maps the impact of frost on corn crops

How did humans develop sharp vision? Lab-grown retinas show likely answer

Sour grapes? Taste, experience of sour foods depends on individual consumer

At AAAS, professor Krystal Tsosie argues the future of science must be Indigenous-led

From the lab to the living room: Decoding Parkinson’s patients movements in the real world

Research advances in porous materials, as highlighted in the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

Sally C. Morton, executive vice president of ASU Knowledge Enterprise, presents a bold and practical framework for moving research from discovery to real-world impact

Biochemical parameters in patients with diabetic nephropathy versus individuals with diabetes alone, non-diabetic nephropathy, and healthy controls

Muscular strength and mortality in women ages 63 to 99

[Press-News.org] A brake for spinning moleculesThe precise control of the rotational temperature of molecular ions opens up new possibilities for laboratory-based astrochemistry