(Press-News.org) A new evolutionary theory in BioEssays claims that consuming a diet very low in nutrients can extend lifespan in laboratory animals, a finding which could hold clues to promoting healthier ageing in humans.

Scientists have known for decades that severely restricted food intake reduces the incidence of diseases of old age, such as cancer, and increases lifespan.

"This effect has been demonstrated in laboratories around the world, in species ranging from yeast to flies to mice. There is also some evidence that it occurs in primates," says lead author, Dr Margo Adler, an evolutionary biologist at UNSW Australia.

The most widely accepted theory is that this effect evolved to improve survival during times of famine. "But we think that lifespan extension from dietary restriction is more likely to be a laboratory artefact," says Dr Adler.

Lifespan extension is unlikely to occur in the wild, because dietary restriction compromises the immune system's ability to fight off disease and reduces the muscle strength necessary to flee a predator.

"Unlike in the benign conditions of the lab, most animals in the wild are killed young by parasites or predators," says Dr Adler.

"Since dietary restriction appears to extend lifespan in the lab by reducing old-age diseases, it is unlikely to have the same effect on wild animals, which generally don't live long enough to be affected by cancer and other late-life pathologies."

Dietary restriction, however, also leads to increased rates of cellular recycling and repair mechanisms in the body.

The UNSW researchers' new theory is that this effect evolved to help animals continue to reproduce when food is scarce; they require less food to survive because stored nutrients in the cells can be recycled and reused.

It is this effect that could account for the increased lifespan of laboratory animals on very low-nutrient diets, because increased cellular recycling reduces deterioration and the risk of cancer.

"This is the most intriguing aspect, from a human health stand point. Although extended lifespan may simply be a side effect of dietary restriction, a better understanding of these cellular recycling mechanisms that drive the effect may hold the promise of longer, healthier lives for humans," she says.

It may be possible in future, for example, to develop drugs that mimic this effect.

INFORMATION:

Watch the video abstract here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KG2Etkr8Hek&feature=youtu.be

Eat more, die young: Why eating a diet very low in nutrients can extend lifespan

2014-03-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Follow the ant trail for drug design

2014-03-18

This news release is available in German. The path to developing new drugs is a long one. If a target is identified for a new active agent – for instance a particular protein that plays a key role in a disease – an active molecule that binds to the target must then be developed. Pharmaceutical companies trawl through their collections of chemicals for substances that act on the target protein in the desired fashion. However, these compounds are often just the starting point for a long process of adjustment and testing. Chemists use computer simulations to design new ...

Democrats, Republicans see each other as mindless -- unless they pose a threat

2014-03-18

We are less likely to humanize members of groups we don't belong to—except, under some circumstances, when it comes to members of the opposite political party. A study by researchers at New York University and Harvard Business School suggests that we are more prone to view members of the opposite political party as human if we view those individuals as threatening.

"It's hardly surprising that we dehumanize those who are not part of our groups," says Jay Van Bavel, an assistant professor in NYU's Department of Psychology and one of the study's co-authors. "However, what ...

Research on the protein gp41 could help towards designing future vaccinations against HIV

2014-03-18

This news release is available in Spanish. Researchers from the University of Granada have discovered, for the first time, an allosteric interaction (that is, a regulation mechanism whereby enzymes can be activated or de-activated) between this protein, which forms part of the sheath of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and the antibody 2F5 (FAB), a potent virus neutralizer. This important scientific breakthrough could help specialists to understand the mechanisms behind generating immune responses and help towards the design of future vaccines against the HIV ...

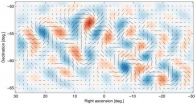

First direct evidence of cosmic inflation

2014-03-18

Almost 14 billion years ago, the universe we inhabit burst into existence in an extraordinary event that initiated the Big Bang. In the first fleeting fraction of a second, the universe expanded exponentially, stretching far beyond the view of our best telescopes. All this, of course, was just theory.

Researchers from the BICEP2 collaboration today announced the first direct evidence for this cosmic inflation. Their data also represent the first images of gravitational waves, or ripples in space-time. These waves have been described as the "first tremors of the Big Bang." ...

Immunologists present improved mass spectrometric method for proteomic analyses

2014-03-18

When it comes to analyzing cell components or body fluids or developing new medications, there is no way around mass spectrometry. Mass spectrometry is a highly sensitive method of measurement that has been used for many years for the analysis of chemical and biological materials. Scientists at the Institute of Immunology of the University Medical Center of Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU) have now significantly improved this analytical method that is widely employed within their field. They have also developed a software program for the integrated analysis of ...

UNH research: Positive memories of exercise spur future workouts

2014-03-18

DURHAM, N.H. – Getting motivated to exercise can be a challenge, but new research from the University of New Hampshire shows that simply remembering a positive memory about exercise may be just what it takes to get on the treadmill. This is the first study to explore how positive memories can influence future workouts.

"This study underscores the power of memory's directive influence in a new domain with practical applications: exercise behaviors. These results provide the first experimental evidence that autobiographical memory activation can be an effective tool in ...

Male, stressed, and poorly social

2014-03-18

Stress, this enemy that haunts us every day, could be undermining not only our health but also our relationships with other people, especially if we are men. In fact, stressed women apparently become more "prosocial". These are the main findings of a study carried out with the collaboration of Giorgia Silani, from the International School for Advanced Studies (SISSA) of Trieste. The study was coordinated by the Social Cognitive Neuroscience Unit of the University of Vienna and saw the participation of the University of Freiburg.

"There's a subtle boundary between the ...

What's so bad about feeling happy?

2014-03-18

Why is being happy, positive and satisfied with life the ultimate goal of so many people, while others steer clear of such feelings? It is often because of the lingering belief that happiness causes bad things to happen, says Mohsen Joshanloo and Dan Weijers of the Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand. Their article, published in Springer's Journal of Happiness Studies, is the first to review the concept of aversion to happiness, and looks at why various cultures react differently to feelings of well-being and satisfaction.

"One of these cultural phenomena ...

Study fingers chickens, quail, in spread of H7N9 influenza virus

2014-03-18

Among the copious species of poultry in China, quail and chickens are the likely sources of infection of H7N9 influenza virus to humans, according to a paper published ahead of print in the Journal of Virology.

"Knowing the likely poultry species lets us target our interventions better to prevent human infections," says corresponding author David Suarez, of the United States Department of Agriculture.

The H7N9 avian influenza virus was first reported in humans in March 2013 in China. Since then over 375 human cases have been confirmed and over 100 have died. Only ...

New understanding of why chromosome errors are high in women's eggs

2014-03-18

A new study from the University of Southampton has provided scientists with a better understanding of why chromosome errors are high in women's eggs.

It is estimated that up to 60 per cent of eggs are affected by errors in how their chromosomes divide, making it the leading cause of infertility. Chromosome errors also lead to conditions such as Down Syndrome and early pregnancy loss.

By using state-of-the-art imaging techniques, the Southampton researchers examined the most important process present in all cells to prevent chromosome errors – the Spindle Assembly Checkpoint ...