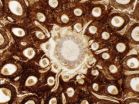

(Press-News.org) Researchers from Lund University and the Swedish Museum of Natural History have made a unique discovery in a well-preserved fern that lived 180 million years ago. Both undestroyed cell nuclei and individual chromosomes have been found in the plant fossil, thanks to its sudden burial in a volcanic eruption.

The well-preserved fossil of a fern from the southern Swedish county of Skåne is now attracting attention in the research community. The plant lived around 180 million years ago, during the Jurassic period, when Skåne was a tropical region where the fauna was dominated by dinosaurs, and volcanoes were a common feature of the landscape. The fossilised fern has been studied using different microscopic techniques, X-rays and geochemical analysis. The examinations reveal that the plant was preserved instantaneously, before it had started to decompose. It was buried abruptly under a volcanic lava flow.

"The preservation happened so quickly that some cells have even been preserved during different stages of cell division", said Vivi Vajda, Professor of Geology at Lund University.

Thanks to the circumstances of the fern's sudden death, the sensitive components of the cells have been preserved. The researchers have found cell nuclei, cell membranes and even individual chromosomes. Such structures are extremely rare finds in fossils, observed Vivi Vajda.

"This naturally leads us to think that there must be more to discover. It isn't hard to imagine what else could be encapsulated in the lava flows at Korsaröd in Skåne", said Vivi Vajda.

Professor Vajda has carried out the study with two researchers from the Swedish Museum of Natural History, Benjamin Bomfleur and Stephen McLoughlin. The fern belonged to the family Osmundaceae, Royal Ferns. In modern times, royal ferns grow in the wild in Sweden and are also a common garden plant. Living representatives of this family are very similar in appearance to the Jurassic fossil, which suggests that only limited evolutionary change has taken place over the millennia. By comparing the size of the cell nuclei in the fossilised plant with its living relatives, the researchers have been able to show that the royal ferns have outstanding evolutionary stability.

"Royal Ferns look essentially the same now as they did during the Jurassic Period, and are therefore an excellent example of what we call a living fossil", said Vivi Vajda.

Professor Vajda has also dated the rocks surrounding the fossil by studying pollen and spores preserved in these rocks. Their analysis revealed that the lava flows are around 180 million years old, from the early Jurassic Period. These results have considerably refined previous radiometric dating conducted on nearby volcano cones. In addition, the research study shows that spores from royal ferns, as well as pollen from coniferous trees, including cypress and cycad, are found in large quantities in the volcanic rock. This is evidence of varied vegetation and a hot, humid climate at the time when the area was engulfed by a disastrous volcanic eruption.

The unique fern fossil was collected in the 1960s, near Korsaröd in central Skåne, by farmer Gustav Andersson who donated the fossil to the Swedish Museum of Natural History. The fossil remained forgotten in the museum's collections for over 40 years before it came to the attention of the researchers. The research findings have now been published in the latest issue of the journal Science.

INFORMATION:

For more information, please contact:

Professor Vivi Vajda

Department of Geology, Lund University

Tel. +46 46 222 46 35, +46 733 86 11 95

vivi.vajda@geol.lu.se

Unique chromosomes preserved in Swedish fossil

2014-03-21

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

A study using Drosophila flies reveals new regulatory mechanisms of cell migration

2014-03-21

Cell migration is highly coordinated and occurs in processes such as embryonic development, wound healing, the formation of new blood vessels, and tumour cell invasion. For the successful control of cell movement, this process has to be determined and maintained with great precision. In this study, the scientists used tracheal cells of the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster to unravel the signalling mechanism involved in the regulation of cell movements.

The research describes a new molecular component that controls the expression of a molecule named Fibroblast Growth ...

Switching an antibiotic on and off with light

2014-03-21

This news release is available in German. Scientists of the KIT and the University of Kiev have produced an antibiotic, whose biological activity can be controlled with light. Thanks to the robust diarylethene photoswitch, the antimicrobial effect of the peptide mimetic can be applied in a spatially and temporally specific manner. This might open up new options for the treatment of local infections, as side effects are reduced. The researchers present their photoactivable antibiotic with the new photomodule in a "Very Important Paper" of the journal "Angewandte Chemie". ...

cfaed presents the new microchip 'Tomahawk 2' at the DATE'14 in Dresden

2014-03-21

The Center for Advancing Electronics Dresden (cfaed) presents its new microchip 'Tomahawk 2' at the DATE'14 Conference in the International Congress Center Dresden from March 24 to 28, 2014. The new Tomahawk is extremely fast, energy-efficient and resilient. It is a heterogeneous multi-processor which can easily integrate very different kinds of devices. The researchers of the Cluster of Excellence for microelectronics of Technische Universität Dresden use the new prototype to prepare the so-called 'tactile internet'. With this, very big data volumes shall be transmitted ...

New study shows we work harder when we are happy

2014-03-21

Happiness makes people more productive at work, according to the latest research from the University of Warwick.

Economists carried out a number of experiments to test the idea that happy employees work harder. In the laboratory, they found happiness made people around 12% more productive.

Professor Andrew Oswald, Dr Eugenio Proto and Dr Daniel Sgroi from the Department of Economics at the University of Warwick led the research.

This is the first causal evidence using randomized trials and piece-rate working. The study, to be published in the Journal of Labor Economics, ...

Surprising new way to kill cancer cells

2014-03-21

Northwestern Medicine scientists have demonstrated that cancer cells – and not normal cells – can be killed by eliminating either the FAS receptor, also known as CD95, or its binding component, CD95 ligand.

"The discovery seems counterintuitive because CD95 has previously been defined as a tumor suppressor," said lead investigator Marcus Peter, professor in medicine-hematology/Oncology at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. "But when we removed it from cancer cells, rather than proliferate, they died."

The findings were published March 20 in Cell Reports. ...

Stem cell study finds source of earliest blood cells during development

2014-03-21

Irvine, Calif., March 20, 2014 — Hematopoietic stem cells are now routinely used to treat patients with cancers and other disorders of the blood and immune systems, but researchers knew little about the progenitor cells that give rise to them during embryonic development.

In a study published April 8 in Stem Cell Reports, Matthew Inlay of the Sue & Bill Gross Stem Cell Research Center and Stanford University colleagues created novel cell assays that identified the earliest arising HSC precursors based on their ability to generate all major blood cell types (red blood ...

New infrared technique aims to remotely detect dangerous materials

2014-03-21

For most people, infrared technology calls to mind soldiers with night-vision goggles or energy audits that identify where heat escapes from homes during the winter season.

But for two Brigham Young University professors, infrared holds the potential to spot from afar whether a site is being used to make nuclear weapons.

Statistics professor Candace Berrett developed a model that precisely characterizes the material in each pixel of an image taken from a long-wave infrared camera. The U.S. National Nuclear Security Administration funded the project through a grant ...

The gene family linked to brain evolution is implicated in severity of autism symptoms

2014-03-21

The same gene family that may have helped the human brain become larger and more complex than in any other animal also is linked to the severity of autism, according to new research from the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus.

The gene family is made up of over 270 copies of a segment of DNA called DUF1220. DUF1220 codes for a protein domain – a specific functionally important segment within a protein. The more copies of a specific DUF1220 subtype a person with autism has, the more severe the symptoms, according to a paper published in the PLoS Genetics. ...

Stanford professor maps by-catch as unintended consequence of global fisheries

2014-03-21

Seabirds, sea turtles and marine mammals such as dolphins may not appear to have much in common, other than an affinity for open water. The sad truth is that they are all unintended victims – by-catch – of intensive global fishing. In fact, accidental entanglement in fishing gear is the single biggest threat to some species in these groups.

A new analysis co-authored by Stanford biology Professor Larry Crowder provides an unprecedented global map of this by-catch, starkly illustrating the scope of the problem and the need to expand existing conservation efforts in certain ...

Homeless with TBI more likely to visit ER

2014-03-21

TORONTO, March 21, 2014—Homeless and vulnerably housed people who have suffered a traumatic brain injury at some point in their life are more likely to visit an Emergency Department, be arrested or incarcerated, or be victims of physical assault, new research has found.

"Given the high costs of Emergency Department visits and the burden of crime on society, these findings have important public health and criminal justice implications," the researchers from St. Michael's Hospital wrote today in the Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation.

Traumatic brain injuries, such as ...