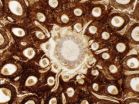

(Press-News.org) Researchers at LSTM have discovered how unprecedented multiple and extreme-level resistance is generated in mosquitoes found in the rice fields of Tiassalé in southern Côte d'Ivoire. The paper, "CYP6 P450 enzymes and ACE-1 duplication produce extreme and multiple insecticide resistance in the malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae" published in PLoS Genetics today, highlights the combination of stringently-replicated whole genome transcription profiling, in vivo transgenic gene expression and in vitro metabolism assays to identify and validate genes from the P450 detoxification enzyme superfamily which are highly expressed in the adult females from the area.

The problem was discovered in 2011 when the Anopheles gambiae larvae sampled from the rice paddies of Tiassalé were raised to adults and tested using WHO tube bioassays. They proved to be resistant to all four of the insecticide classes available for mosquito control (Edi et al. Emerging Infectious Diseases 18: 1508-1511, 2012). This is the first wild Anopheles population to display such complete multiple resistance, which is a serious concern when preserving effectiveness of insecticides depends on rotating or combining their use. In addition to many of the mosquitoes surviving a standard one-hour insecticide exposure (used as the WHO standard to monitor the prevalence of resistance), the levels of resistance displayed in Tiassalé were very high, with 50% of mosquitoes tested surviving for longer than four hours exposure to both a carbamate and a pyrethroid.

The new work reveals that two members of the P450 gene superfamily in particular are highly expressed in resistant Tiassalé mosquitoes: CYP6M2 and CYP6P3. When these genes were transplanted into Drosophila, resistance to pyrethroids and carbamates was generated in otherwise susceptible fly strains. These genes are familiar candidates to LSTM researchers who have previously documented their links with pyrethroid and DDT resistance. This new research shows how specific P450 genes can engender resistance across insecticides with entirely different modes of action: DDT and pyrethroids target a voltage-gated sodium channel (a nerve cell membrane channel), whereas carbamates and organophosphates target the neurotransmitter Acetylcholinesterase, encoded by the gene ACE-1. This is where Tiassalé mosquitoes yielded another surprise, contributing to their exceptionally high carbamate resistance,. A well-known single nucleotide resistance mutation at the ACE-1 gene is near ubiquitous in the population, but because almost every female is a heterozygote (possesses a resistant and susceptible allele) it did not seem this could cause any variation in resistance. However, from application of a newly-developed qPCR diagnostic it was found that the ACE-1 gene was duplicated in some individuals, with those resistant to carbamate much more likely to have additional, duplicated copies of the resistant ACE-1 allele.

This combination of distinct mechanisms provides the Anopheles population of Tiassalé with high levels of resistance and resistance across insecticides. Dr David Weetman senior author, said: "The work has given a uniquely detailed insight into the varied mechanisms through which mosquitoes can become resistant to the available arsenal of insecticides. Controlling populations like Tiassalé will be particularly challenging, but understanding of their resistance mechanisms provides tools for monitoring in other west African populations, to help maintain the effectiveness of vector control programmes."

INFORMATION:

Note to Editors:

The research was funded in part by AvecNet

To read the article, please follow this link http://www.plosgenetics.org/doi/pgen.1004236

For further information, please contact:

Mrs Clare Bebb

Senior Media Officer

Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine

Office: +44 (0)151 705 3135

Mobile: +44 (0)7889535222

Email: c.bebb@liv.ac.uk

Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (LSTM) has been engaged in the fight against infectious, debilitating and disabling diseases since 1898 and continues that tradition today with a research portfolio in excess of well over £200 million and a teaching programme attracting students from over 65 countries.

For further information, please visit: http://www.lstmliverpool.ac.uk

Researchers at LSTM unlock the secret of multiple insecticide resistance in mosquitoes

Paper shows mechanisms by which multiple and cross resistance are achieved

2014-03-21

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Critical illness polyneuropathy and myopathy: Nerve injury and regeneration

2014-03-21

Critical illness polyneuropathy and critical illness myopathy are frequent complications of severe illness that involve sensorimotor axons and skeletal muscles, respectively. Differentiating critical illness polyneuropathy from Guillain-Barré syndrome, especially the axonal variants, may be difficult on purely clinical grounds, as Guillain-Barré syndrome is known for its variable atypical manifestations. Prof. Hongliang Zhang and team from the First Bethune Hospital, Jilin University in China provide the latest knowledge concerning the pathophysiology of critical illness ...

Lessons offered by emerging carbon trading markets

2014-03-21

DURHAM, N.C. -- Although markets for trading carbon emission credits to reduce greenhouse gas emissions have stalled in United States federal policy-making, carbon markets are emerging at the state level within the U.S. and around the world, teaching us more about what does and doesn't work.

In a Policy Forum article in the March 21 edition of Science magazine, Duke University's Richard Newell, William Pizer and Daniel Raimi discuss the key lessons from a decade of experience with carbon markets. They also discuss what it might take for these markets to develop and possibly ...

Who reprograms rat astrocytes into neurons?

2014-03-21

To date, it remains poorly understood whether astrocytes can be easily reprogrammed into neurons. Mash1 and Brn2 have been previously shown to cooperate to reprogram fibroblasts into neurons. Dr. Yongjun Wang and team from Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine in China found that and found that Brn2 was expressed in astrocytes from 2-month-old Sprague-Dawley rats, but Mash1 was not detectable. Thus, the researchers hypothesized that Mash1 alone could be used to reprogram astrocytes into neurons. Murine stem cell virus (MSCV)-Mash1 recombinant plasmid was constructed ...

Unique chromosomes preserved in Swedish fossil

2014-03-21

Researchers from Lund University and the Swedish Museum of Natural History have made a unique discovery in a well-preserved fern that lived 180 million years ago. Both undestroyed cell nuclei and individual chromosomes have been found in the plant fossil, thanks to its sudden burial in a volcanic eruption.

The well-preserved fossil of a fern from the southern Swedish county of Skåne is now attracting attention in the research community. The plant lived around 180 million years ago, during the Jurassic period, when Skåne was a tropical region where the fauna was dominated ...

A study using Drosophila flies reveals new regulatory mechanisms of cell migration

2014-03-21

Cell migration is highly coordinated and occurs in processes such as embryonic development, wound healing, the formation of new blood vessels, and tumour cell invasion. For the successful control of cell movement, this process has to be determined and maintained with great precision. In this study, the scientists used tracheal cells of the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster to unravel the signalling mechanism involved in the regulation of cell movements.

The research describes a new molecular component that controls the expression of a molecule named Fibroblast Growth ...

Switching an antibiotic on and off with light

2014-03-21

This news release is available in German. Scientists of the KIT and the University of Kiev have produced an antibiotic, whose biological activity can be controlled with light. Thanks to the robust diarylethene photoswitch, the antimicrobial effect of the peptide mimetic can be applied in a spatially and temporally specific manner. This might open up new options for the treatment of local infections, as side effects are reduced. The researchers present their photoactivable antibiotic with the new photomodule in a "Very Important Paper" of the journal "Angewandte Chemie". ...

cfaed presents the new microchip 'Tomahawk 2' at the DATE'14 in Dresden

2014-03-21

The Center for Advancing Electronics Dresden (cfaed) presents its new microchip 'Tomahawk 2' at the DATE'14 Conference in the International Congress Center Dresden from March 24 to 28, 2014. The new Tomahawk is extremely fast, energy-efficient and resilient. It is a heterogeneous multi-processor which can easily integrate very different kinds of devices. The researchers of the Cluster of Excellence for microelectronics of Technische Universität Dresden use the new prototype to prepare the so-called 'tactile internet'. With this, very big data volumes shall be transmitted ...

New study shows we work harder when we are happy

2014-03-21

Happiness makes people more productive at work, according to the latest research from the University of Warwick.

Economists carried out a number of experiments to test the idea that happy employees work harder. In the laboratory, they found happiness made people around 12% more productive.

Professor Andrew Oswald, Dr Eugenio Proto and Dr Daniel Sgroi from the Department of Economics at the University of Warwick led the research.

This is the first causal evidence using randomized trials and piece-rate working. The study, to be published in the Journal of Labor Economics, ...

Surprising new way to kill cancer cells

2014-03-21

Northwestern Medicine scientists have demonstrated that cancer cells – and not normal cells – can be killed by eliminating either the FAS receptor, also known as CD95, or its binding component, CD95 ligand.

"The discovery seems counterintuitive because CD95 has previously been defined as a tumor suppressor," said lead investigator Marcus Peter, professor in medicine-hematology/Oncology at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. "But when we removed it from cancer cells, rather than proliferate, they died."

The findings were published March 20 in Cell Reports. ...

Stem cell study finds source of earliest blood cells during development

2014-03-21

Irvine, Calif., March 20, 2014 — Hematopoietic stem cells are now routinely used to treat patients with cancers and other disorders of the blood and immune systems, but researchers knew little about the progenitor cells that give rise to them during embryonic development.

In a study published April 8 in Stem Cell Reports, Matthew Inlay of the Sue & Bill Gross Stem Cell Research Center and Stanford University colleagues created novel cell assays that identified the earliest arising HSC precursors based on their ability to generate all major blood cell types (red blood ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

Yes! The role of YAP and CTGF as potential therapeutic targets for preventing severe liver disease

Pancreatic cancer may begin hiding from the immune system earlier than we thought

Robotic wing inspired by nature delivers leap in underwater stability

A clinical reveals that aniridia causes a progressive loss of corneal sensitivity

Fossil amber reveals the secret lives of Cretaceous ants

Predicting extreme rainfall through novel spatial modeling

The Lancet: First-ever in-utero stem cell therapy for fetal spina bifida repair is safe, study finds

Nanoplastics can interact with Salmonella to affect food safety, study shows

Eric Moore, M.D., elected to Mayo Clinic Board of Trustees

NYU named “research powerhouse” in new analysis

New polymer materials may offer breakthrough solution for hard-to-remove PFAS in water

Biochar can either curb or boost greenhouse gas emissions depending on soil conditions, new study finds

Nanobiochar emerges as a next generation solution for cleaner water, healthier soils, and resilient ecosystems

Study finds more parents saying ‘No’ to vitamin K, putting babies’ brains at risk

Scientists develop new gut health measure that tracks disease

Rice gene discovery could cut fertiliser use while protecting yields

Jumping ‘DNA parasites’ linked to early stages of tumour formation

Ultra-sensitive CAR T cells provide potential strategy to treat solid tumors

Early Neanderthal-Human interbreeding was strongly sex biased

North American bird declines are widespread and accelerating in agricultural hotspots

Researchers recommend strategies for improved genetic privacy legislation

How birds achieve sweet success

More sensitive cell therapy may be a HIT against solid cancers

Scientists map how aging reshapes cells across the entire mammalian body

Hotspots of accelerated bird decline linked to agricultural activity

How ancient attraction shaped the human genome

NJIT faculty named Senior Members of the National Academy of Inventors

[Press-News.org] Researchers at LSTM unlock the secret of multiple insecticide resistance in mosquitoesPaper shows mechanisms by which multiple and cross resistance are achieved