(Press-News.org) Wikipedia lists 65 adjectives that botanists use to describe the shapes of plant leaves. In English (rather than Latin) they mean the leaf is lance-shaped, spear-shaped, kidney-shaped, diamond shaped, arrow-head-shaped, egg-shaped, circular, spoon-shaped , heart-shaped, tear-drop-shaped or sickle-shaped — among other possibilities.

How does the plant "know" how to make these shapes? The answer is by controlling the distribution of a plant hormone called auxin, which determines the rate at which plant cells divide and lengthen.

But how can one molecule make so many different patterns? Because the hormone's effects are mediated by the interplay between large families of proteins that either step on the gas or put on the brake when auxin is around.

In recent years as more and more of these proteins were discovered, the auxin signaling machinery began to seem baroque to the point of being unintelligible.

Now the Strader and Jez labs at Washington University in St. Louis have made a discovery about one of the proteins in the auxin signaling network that may prove key to understanding the entire network.

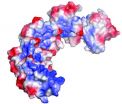

In the March 24 issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences they explain that they were able to crystallize a key protein called a transcription factor and work out its structure. The interaction domain of the protein, they learned, folds into a flat paddle with a positively charged face and a negatively charged face. These faces allow the proteins to snap together like magnets, forming long chains, or oligomers.

We have some evidence that proteins chain in plant cells as well as in solution, said senior author Lucia Strader, PhD, assistant professor of biology and an auxin expert. By varying the length of these chains, plants may fine-tune the response of individual cells to auxin to produce detailed patterns such as the toothed lobes of the cilantro leaf.

Combinatorial explosion

Sculpting leaves is just one of many roles auxin plays in plants. Among other things the hormone helps make plants bend toward the light, roots grow down and shoots grow up, fruits develop and fruits fall off.

"The most potent form of the hormone is indole-3-acetic acid, abbreviated IAA, and my lab members joke that IAA really stands for Involved in Almost Everything," Strader said.

The backstory here is that whole families of proteins intervene between auxin and genes that respond to auxin by making proteins. In the model plant Aribidopsis thaliana these include 5 transcription factors that activate genes when auxin is present (called ARFs) and 29 repressor proteins that block the transcription factors by binding to them (Aux/IAA proteins). A third family marks repressors for destruction.

"Different combinations of these proteins are present in each cell," said Strader. "On top of that, some combinations interact more strongly than others and some of the transcription factors also interact with one another."

In an idle moment David Korasick, a graduate fellow in the Strader and Jez labs and first author on the PNAS article, did a back-of-the-envelope calculation to put a number on the complexity of the system they were trying to understand. From a strictly mathematical point of view there are 3,828 possible combinations of the auxin-related Arabidopsis proteins. That is assuming interactions involve only one of each type of protein; if multiples are possible, the number, of course, explodes.

To make any headway, Strader said, we had a better understanding of how these proteins interact. The rule in protein chemistry is the opposite of the one in design: instead of form following function, function follows form.

So to figure out a protein's form — the way it folds in space — they turned to the Jez lab, which specializes in protein crystallography, essentially a form of high-resolution microscopy that allows protein structures to be visualized at the atomic level.

Korasick had the job of crystallizing ARF7, a transcription factor that helps, Arabidopsis bend toward the light. With the help of Joseph Jez, PhD, associate professor of biology, Corey Westfall, and Soon Goo Lee), Korasick cut "floppy bits" off the protein that might have made it hard to crystallize, leaving just the part of the protein where it interacts with repressor molecules.

After he had that construct, crystallization was remarkably fast. He set up his first drops in solution wells on the 4th of July. The protein crystallized with a fuss, and he ran the crystals up to the Advanced Photon Source at the Argonne National Laboratory outside Chicago. By August 1 he had the diffraction data he needed to solve the protein's structure.

Surprise, surprise

The previous model for the interaction between a repressor and a transcription factor – a model that had stood for 15 years, Strader said– was that the repressor lay flat on the transcription factor, two domains on the repressor matching up with the corresponding two domains on the transcription factor.

The structural model Korasick developed showed that the two domains fold together to form a single domain, called a PB1 domain. A PB1 domain is a protein interaction module that can be found in animals and fungi as well as plants.

Strader, Jez et al.

The transcription factor ARF7 turned out to have a magnet-like interaction region, called a PB1 domain ,with positively (blue) and negatively (red) charged faces.

The repressor proteins, which are predicted to have PB1 domains identical to that of the ARF transcription factor, then stick to one or the other side of the transcription factor's PB1 domain, preventing it from doing its job. Experiments showed that there had to be a repressor protein stuck to both faces of the transcription factor's PB1 domain to repress the activity of auxin.

This means the model, which pairs a single repressor protein with a single transcription factor, is wrong, Strader said.

"Nor can we limit the interactions to just two," she said. "It could be hundreds for all we know."

In Korasick's crystal five of the ARF7 PB1 domains stuck to one another, forming a pentamer.

"I like to think of the PB1 domains as magnets, " Strader said. "Like magnets, they can stick together, back-to-front, to form long chains."

"But we have to put an asterisk next to that," Korasick said, "because it's possible it's an artifact of crystallography and doesn't work that way in living plants."

But both Strader and Korasick suspect that it does. Strader points out that the complexity of the auxin signaling system has increased over evolutionary time as plants became fancier. A simple plant like the moss Physcomitrella patens has fewer signaling proteins than a complicated plant like soybean.

"Probably what that's saying is that it's really, really important for a plant to be able to modulate auxin signaling, to have the right amount in each cell, to balance positive and negative growth," Korasick said.

"The difference between plants and animals," said Strader, "is that plants have rigid cell walls. So when a plant cell decides to divide itself or length itself, that's a permanent decision, which is why it's so tightly controlled."

INFORMATION: END

Scientists find a molecular clue to the complex mystery of auxin signaling in plants

Interaction domain on proteins that modulate this potent hormone allows them to stack back-to-front like button magnets

2014-03-25

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Innovative technique provides inexpensive, rapid and detailed analysis of proteins

2014-03-25

Proteins are vital participants in virtually all life processes, including growth, repair and signaling in cells; catalysis of chemical reactions and defense against infection. For these reasons, proteins can provide critical signposts of health and disease, provided they can be identified and assessed in a clinical setting.

Accurately characterizing proteins for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes has been an enormous challenge for the medical community. At the Biodesign Institute's Molecular Biomarkers Laboratory at Arizona State University, research focuses on the ...

Researchers take mathematical route to fighting viruses

2014-03-25

Mathematicians at the University of York have joined forces with experimentalists at the University of Leeds to take an important step in discovering how viruses make new copies of themselves during an infection.

The researchers have constructed a mathematical model that provides important new insights about the molecular mechanisms behind virus assembly which helps to explain the efficiency of their operation.

The discovery opens up new possibilities for the development of anti-viral therapies and could help in the treatment of a range of diseases from HIV and Hepatitis ...

A new concept for manufacturing wrinkling patterns on hard nano-film/soft-matter substrate

2014-03-25

Wrinkling is a common phenomenon for thin stiff film adhered on soft substrate. Various wrinkling phenomenon has been reported previously. Wu Dan, Yin Yajun, Xie Huimin,et al from Tsinghua University proposed a new method to control wrinkling and buckling of thin stiff film on soft substrate. It is found that the curve pattern on the soft substrate has obvious influence on the wrinkling distribution of the thin film/soft substrate. Their work, entitled "Controlling the surface buckling wrinkles by patterning the material system of hard-nano-film/soft-matter-substrate", ...

Psychiatric complications in women with PCOS often linked to menstrual irregularity

2014-03-25

(NEW YORK, NY, March 24, 2014) – Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), a hormone imbalance that causes infertility, obesity, and excessive facial hair in women, can also lead to severe mental health issues including anxiety, depression, and eating disorders. A study supervised by Columbia University School of Nursing professor Nancy Reame, MSN, PhD, FAAN, and published in the Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, identifies the PCOS complications that may be most responsible for psychiatric problems. While weight gain and unwanted body hair can be distressing, irregular ...

Shorter sleepers are over-eaters

2014-03-25

Young children who sleep less eat more, which can lead to obesity and related health problems later in life, reports a new study by UCL researchers.

The study found that 16 month-old children who slept for less than 10 hours each day consumed on average 105kcal more per day than children who slept for more than 13 hours. This is an increase of around 10% from 982kcal to 1087kcal.

Associations between eating, weight and sleep have been reported previously in older children and adults, but the study, published in the International Journal of Obesity, is the first to directly ...

Instant immune booster dramatically improves outcome of bacterial meningitis and pneumonia

2014-03-25

AUDIO:

This is a podcast interview with Professor Schwaeble.

Click here for more information.

"I am really excited about this landmark discovery. We demonstrate that boosting the innate immune system can have a significant impact on the body's ability to defend itself against life-threatening infections" - Professor Wilhelm Schwaeble from the University of Leicester's Department of Infection, Immunity and Inflammation

IMAGES AND A PODCAST INTERVIEW WITH PROFESSOR SCHWAEBLE ...

Protein plays key role in infection by oral pathogen

2014-03-25

CAMBRIDGE, Mass., March 24 — Scientists at Forsyth, along with a colleague from Northwestern University, have discovered that the protein, Transgultaminase 2 (TG2), is a key component in the process of gum disease. TG2 is widely distributed inside and outside of human cells. The scientists found that blocking some associations of TG2 prevents the bacteria Porphyromonas gingivalis (PG) from adhering to cells. This insight may one day help lead to novel therapies to prevent gum disease caused by PG.

Periodontal, or gum, disease is one of the most common infectious diseases. ...

Studying crops, from outer space

2014-03-25

Washington, D.C.— Plants convert energy from sunlight into chemical energy during a process called photosynthesis. This energy is passed on to humans and animals that eat the plants, and thus photosynthesis is the primary source of energy for all life on Earth. But the photosynthetic activity of various regions is changing due to human interaction with the environment, including climate change, which makes large-scale studies of photosynthetic activity of interest. New research from a team including Carnegie's Joe Berry reveals a fundamentally new approach for measuring ...

Violent video games associated with increased aggression in children

2014-03-25

Bottom Line: Habitually playing violent video games appears to increase aggression in children, regardless of parental involvement and other factors.

Author: Douglas A. Gentile, Ph.D., of Iowa State University, Ames, and colleagues.

Background: More than 90 percent of American youths play video games, and many of these games depict violence, which is often portrayed as fun, justified and without negative consequences.

How the Study Was Conducted: The authors tracked children and adolescents in Singapore over three years on self-reported measures of gaming habits, ...

E-cigarettes not associated with more smokers quitting, reduced consumption

2014-03-25

Bottom Line: The use of electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) by smokers is not associated with greater rates of quitting cigarettes or reduced cigarette consumption after one year.

Author: Rachel A. Grana, Ph.D., M.P.H., and colleagues from the University California, San Francisco.

Background: E-cigarettes are promoted as smoking cessation tools, but studies of their effectiveness have been unconvincing.

How the Study Was Conducted: The authors analyzed self-reported data from 949 smokers (88 of the smokers used e-cigarettes at baseline) to determine if e-cigarettes ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

How rice plants tell head from toe during early growth

Scientists design solar-responsive biochar that accelerates environmental cleanup

Construction of a localized immune niche via supramolecular hydrogel vaccine to elicit durable and enhanced immunity against infectious diseases

Deep learning-based discovery of tetrahydrocarbazoles as broad-spectrum antitumor agents and click-activated strategy for targeted cancer therapy

DHL-11, a novel prieurianin-type limonoid isolated from Munronia henryi, targeting IMPDH2 to inhibit triple-negative breast cancer

Discovery of SARS-CoV-2 PLpro inhibitors and RIPK1 inhibitors with synergistic antiviral efficacy in a mouse COVID-19 model

Neg-entropy is the true drug target for chronic diseases

Oxygen-boosted dual-section microneedle patch for enhanced drug penetration and improved photodynamic and anti-inflammatory therapy in psoriasis

Early TB treatment reduced deaths from sepsis among people with HIV

Palmitoylation of Tfr1 enhances platelet ferroptosis and liver injury in heat stroke

Structure-guided design of picomolar-level macrocyclic TRPC5 channel inhibitors with antidepressant activity

Therapeutic drug monitoring of biologics in inflammatory bowel disease: An evidence-based multidisciplinary guidelines

New global review reveals integrating finance, technology, and governance is key to equitable climate action

New study reveals cyanobacteria may help spread antibiotic resistance in estuarine ecosystems

Around the world, children’s cooperative behaviors and norms converge toward community-specific norms in middle childhood, Boston College researchers report

How cultural norms shape childhood development

University of Phoenix research finds AI-integrated coursework strengthens student learning and career skills

Next generation genetics technology developed to counter the rise of antibiotic resistance

Ochsner Health hospitals named Best-in-State 2026

A new window into hemodialysis: How optical sensors could make treatment safer

High-dose therapy had lasting benefits for infants with stroke before or soon after birth

‘Energy efficiency’ key to mountain birds adapting to changing environmental conditions

Scientists now know why ovarian cancer spreads so rapidly in the abdomen

USF Health launches nation’s first fully integrated institute for voice, hearing and swallowing care and research

Why rethinking wellness could help students and teachers thrive

Seabirds ingest large quantities of pollutants, some of which have been banned for decades

When Earth’s magnetic field took its time flipping

Americans prefer to screen for cervical cancer in-clinic vs. at home

Rice lab to help develop bioprinted kidneys as part of ARPA-H PRINT program award

Researchers discover ABCA1 protein’s role in releasing molecular brakes on solid tumor immunotherapy

[Press-News.org] Scientists find a molecular clue to the complex mystery of auxin signaling in plantsInteraction domain on proteins that modulate this potent hormone allows them to stack back-to-front like button magnets