(Press-News.org) Researchers at King's College London and Imperial College London have discovered that people with fewer copies of a gene coding for a carb-digesting enzyme may be at higher risk of obesity. The findings, published in Nature Genetics, suggest that dietary advice may need to be more tailored to an individual's digestive system, based on whether they have the genetic predisposition and necessary enzymes to digest different foods.

Salivary amylase plays a significant role in breaking down carbohydrates in the mouth at the start of the digestion process. The new study suggests that people with fewer copies of the AMY1 gene have lower levels of this enzyme and therefore will have more difficulty breaking down carbohydrates than those with more copies.

Previous research has found a genetic link between obesity and food behaviours and appetite, but the new discovery highlights a novel genetic link between metabolism and obesity. It suggests that people's bodies may react differently to the same type and amount of food, leading to weight gain in some and not in others. The effect of the genetic difference found in the latest study appears much stronger link than any of those found before.

Researchers first measured gene expression patterns in 149 Swedish families with differences in the levels of obesity and found unusual patterns around two amylase genes (AMY1 and AMY2), which code for salivary and pancreatic amylase. This was suggestive of a variation in copy numbers relating directly to obesity.

The finding was replicated strongly in 972 twins from TwinsUK, the biggest UK adult twin registry, which found a similar pattern of expression. The researchers then estimated the precise copy numbers of the amylase gene in the DNA of a further 481 Swedish subjects, 1,479 subjects from TwinsUK and 2,137 subjects from the DESIR project.

The collaborative team found that the number of copies of the AMY1 gene (salivary amylase) was consistently linked to obesity. Further replication in French and Chinese patients with and without obesity showed the same patterns.

A lower estimated AMY1 copy-number showed a significantly increased risk of obesity in all samples and this translated to an approximate eight-fold difference in the risk of obesity between those subjects with the highest number of copies of the gene and those with the lowest.

Standard Genome wide mapping methods (GWAS) had missed this strong association as the area is technically hard to map. This variation in copy numbers, also known as 'copy number variants' (CNV) has been underestimated as a genetic cause of disease, but the link between CNV in the amylase gene and obesity provides an indication that other major diseases may be influenced by similar mechanisms.

Professor Tim Spector, Head of the Department of Twin Research and Genetic Epidemiology at King's College London and joint lead investigator said: "These findings are very exciting. While studies to date have mainly found small effect genes that alter eating behaviour, we discovered how the digestive 'tools' in your metabolism vary between people – and the genes coding for these – can have a large influence on your weight.

"The next step is to find out more about the activity of this digestive enzyme, and whether this might prove a useful biomarker or target for the treatment of obesity.

"In the future, a simple blood or saliva test might be used to measure levels of key enzymes such as amylase in the body and therefore shape dietary advice for both overweight and underweight people. Treatments are a long way away but this is an important step in realising that all of us digest and metabolise food differently – and we can move away from 'one-size fits all diets' to more personalised approaches."

INFORMATION: END

New study finds strong link between obesity and 'carb breakdown' gene

2014-03-30

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Earth's dynamic interior

2014-03-30

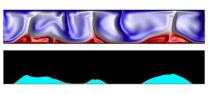

VIDEO:

This video shows a numerical simulation of Earth's deep mantle. The top panel is temperature and the bottom panel is composition which includes three components: the more-primitive reservoir at the...

Click here for more information.

TEMPE, Ariz. – Seeking to better understand the composition of the lowermost part of Earth's mantle, located nearly 2,900 kilometers (1,800 miles) below the surface, a team of Arizona State University researchers has developed new simulations ...

Heat-conducting polymer cools hot electronic devices at 200 degrees C

2014-03-30

Polymer materials are usually thermal insulators. But by harnessing an electropolymerization process to produce aligned arrays of polymer nanofibers, researchers have developed a thermal interface material able to conduct heat 20 times better than the original polymer. The modified material can reliably operate at temperatures of up to 200 degrees Celsius.

The new thermal interface material could be used to draw heat away from electronic devices in servers, automobiles, high-brightness LEDs and certain mobile devices. The material is fabricated on heat sinks and heat ...

Scientists pinpoint why we miss subtle visual changes, and why it keeps us sane

2014-03-30

Ever notice how Harry Potter's T-shirt abruptly changes from a crewneck to a henley shirt in "The Order of the Phoenix," or how in "Pretty Woman," Julia Roberts' croissant inexplicably morphs into a pancake? Don't worry if you missed those continuity bloopers. Vision scientists at the University of California, Berkeley, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have discovered an upside to the brain mechanism that can blind us to subtle changes in movies and in the real world.

They've discovered a "continuity field" in which the brain visually merges similar objects ...

A new approach to Huntington's disease?

2014-03-30

Tweaking a specific cell type's ability to absorb potassium in the brain improved walking and prolonged survival in a mouse model of Huntington's disease, reports a UCLA study published March 30 in the online edition of Nature Neuroscience. The discovery could point to new drug targets for treating the devastating disease, which strikes one in every 20,000 Americans.

Huntington's disease is passed from parent to child through a mutation in the huntingtin gene. By killing brain cells called neurons, the progressive disorder gradually deprives patients of their ability ...

Erasing a genetic mutation

2014-03-30

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Using a new gene-editing system based on bacterial proteins, MIT researchers have cured mice of a rare liver disorder caused by a single genetic mutation.

The findings, described in the March 30 issue of Nature Biotechnology, offer the first evidence that this gene-editing technique, known as CRISPR, can reverse disease symptoms in living animals. CRISPR, which offers an easy way to snip out mutated DNA and replace it with the correct sequence, holds potential for treating many genetic disorders, according to the research team.

"What's exciting about ...

Effect of important air pollutants may be absent from key precipitation observations

2014-03-30

Pioneering new research from the University of Exeter could have a major impact on climate and environmental science by drastically transforming the perceived reliability of key observations of precipitation, which includes rain, sleet and snow.

The ground breaking study examines the effect that increased aerosol concentrations in the atmosphere, emitted as a result of burning fossil fuels, had on regional temperature and precipitation levels.

Scientists from Exeter's Mathematics department compared observed regional temperature and precipitation changes throughout ...

Genetic mutations warn of skin cancer risk

2014-03-30

Researchers have discovered that mutations in a specific gene are responsible for a hereditary form of melanoma.

Every year in the UK, almost 12,000 people are diagnosed with melanoma, a form of skin cancer. About 1 in 20 people with melanoma have a strong family history of the disease. In these patients, pinpointing the genetic mutations that drive disease development allows dermatologists to identify people who should be part of melanoma surveillance programmes.

The team found that people with specific mutations in the POT1 gene were extremely likely to develop melanoma. ...

Scripps Florida scientists offer 'best practices' nutrition measurement for researchers

2014-03-30

JUPITER, FL, March 30, 2014 – At first glance, measuring what the common fruit fly eats might seem like a trivial matter, but it is absolutely critical when it comes to conducting studies of aging, health, metabolism and disease. How researchers measure consumption can make all the difference in the accuracy of a study's conclusions.

Scientists from the Florida campus of The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) have developed what amounts to a best practices guide to the most accurate way of measuring fruit fly food consumption that could lead to more informed research and ...

Researchers identify new protein markers that may improve understanding of heart disease

2014-03-30

Researchers at the Intermountain Medical Center Heart Institute in Murray, Utah, have discovered that elevated levels of two recently identified proteins in the body are inflammatory markers and indicators of the presence of cardiovascular disease.

These newly identified markers of inflammation, GlycA and GlycB, have the potential to contribute to better understanding of the inflammatory origins of heart disease and may be used in the future to identify a heart patient's future risk of suffering a heart attack, stroke, or even death.

Inflammation occurs in the body ...

Study compares heart valve systems

2014-03-30

Among patients undergoing aortic valve replacement using a catheter tube, a comparison of two types of heart valve technologies, balloon-expandable or self-expandable valve systems, found a greater rate of device success with the balloon-expandable valve, according to a JAMA study released online to coincide with presentation at the 2014 American College of Cardiology Scientific Sessions.

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) has emerged as a new option for patients with severe narrowing of the aortic valve and as an effective alternative treatment method to ...