(Press-News.org) ST. LOUIS -- Removing pressure from medical school while teaching students skills to manage stress and bounce back from adversity improves their mental health and boosts their academic achievement, Saint Louis University research finds.

Stuart Slavin, M.D., M.Ed., associate dean for curriculum at SLU School of Medicine, is the lead author of the paper, which is published the April edition of Academic Medicine. The problem of depression among medical school students is significant, Slavin said, affecting between 20 and 30 percent of medical students in the U.S., and potentially compromising their mental health for years to come.

The study looks at the well-being of first and second year students before and after changes to Saint Louis University's medical school curriculum that are designed to prevent depression, stress and anxiety. It compared the performance of five classes of 175 to 178 students – two before the changes and three after – measured at medical school orientation, the end of year one and the end of year two.

"We've seen dramatic improvement in the mental health of our students. Depression rates in first year medical students went from 27 percent to 11 percent and anxiety dropped from 55 percent to 31 percent. At the same time, our Step 1 board scores went up, meaning student performance improved," Slavin said. "Our students know more, and will be in a better situation, emotionally, to care for our patients."

The first of many licensing exams, the Step 1 boards are given to medical school students at the end of their second year to assess whether students can apply basic science concepts to medical questions. Scores help determine admission to residency programs.

For about 60 years, administrators have recognized the number of students who feel depressed or anxious increases during their time in medical school, Slavin said.

"For many years, nobody did anything about it," he said. "Then, the first approach to addressing the problem was to get students better access to psychiatric and mental health services. That was followed by schools adding activities that encourage wellness and teamwork, such as Olympics-style athletic competitions and optional wellness seminars. While those things are great, they're not enough."

SLU administrators decided to take stress reduction beyond offering resources and wellness activities. They started by asking student why they felt anxious and depressed.

"We decided to design and implement curricular changes that would directly address these stressors and would produce a less toxic educational environment," Slavin said.

Without sacrificing critical educational components, SLU changed its curriculum to remove unnecessary stressors, a dramatic paradigm shift from seeing stress as an inevitable part of the path to becoming a doctor, and added a required class that teaches strategies to de-stress, Slavin said.

"The approach is preventive and the model is very simple. We tried to reduce or eliminate unnecessary stressors in the learning environment itself. At the same time, we helped students develop skills in resilience and mindfulness to better manage stress and find some measure of well-being."

The curriculum was changed so students receive pass or fail grades for their pre-clinical courses in the first two years of medical school, which is a practice adopted at about 40 other medical schools, rather than letter grades or honors/ near honors grading systems. They spend fewer hours in the classroom, giving them more free time, choice and control over their schedules to explore expanded electives and engage in newly established learning communities. In addition, SLU modified the content of some classes and the order they were taught.

Students also take a short, focused course that helps them develop lifelong strategies to cope with stress.

The class teaches students to better manage energy by taking breaks, sleeping, eating properly and exercising; being mindful or paying close attention to what's happening in the present moment; reframing their perspective to be more realistic; recognizing negativity; controlling their reactions to situations; and cultivating a positive and optimistic outlook that ultimately leads to more happiness and personal satisfaction.

In addition to exhibiting lower rates of depression symptoms and less anxiety and stress, students who followed the new curriculum felt more connected to each other than the pre-change group.

It's important to our health care system to address depression and stress among medical school students, Slavin said.

"Physician depression and burnout are significant problems in the United States and may rightly be viewed as a substantial public health problem, particularly given the evidence of the negative impact that mental health can have on clinical care by reducing physician empathy and increasing rates of medical error," he said.

"Unfortunately strong evidence supports that the seeds of these mental health problems are planted in medical school."

The lessons learned from the curriculum changes can be applied in any high pressure environment – from high schools to the most competitive law firm, Slavin believes.

"Everybody is feeling so much stress these days. We need to try to find ways to prevent it when possible and better deal with stress when we can't."

INFORMATION:

Established in 1836, Saint Louis University School of Medicine has the distinction of awarding the first medical degree west of the Mississippi River. The school educates physicians and biomedical scientists, conducts medical research, and provides health care on a local, national and international level. Research at the school seeks new cures and treatments in five key areas: infectious disease, liver disease, cancer, heart/lung disease, and aging and brain disorders.

Kinder, gentler med school: Students less depressed, learn more

Curriculum changes, resilience training lowers anxiety, SLU research shows

2014-03-31

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Poor sleep quality linked to cognitive decline in older men

2014-03-31

DARIEN, IL – A new study of older men found a link between poor sleep quality and the development of cognitive decline over three to four years.

Results show that higher levels of fragmented sleep and lower sleep efficiency were associated with a 40 to 50 percent increase in the odds of clinically significant decline in executive function, which was similar in magnitude to the effect of a five-year increase in age. In contrast, sleep duration was not related to subsequent cognitive decline.

"It was the quality of sleep that predicted future cognitive decline in this ...

Psychological factors turn young adults away from HIV intervention counseling

2014-03-31

PHILADELPHIA (March 31, 2014) – Keeping young people in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) prevention programs is a major goal in reducing the incidence of HIV, and multi-session interventions are often more effective than single-sessions. But according to a new study from the Annenberg School for Communication, the way these programs are designed and implemented may turn off the very people they are trying to help.

The study, "Motivational barriers to retention of at-risk young adults in HIV-prevention interventions: perceived pressure and efficacy," is published in ...

Research shows link between states' personalities and their politics

2014-03-31

One state's citizens are collectively more agreeable and another's are more conscientious. Could that influence how each state is governed?

A recently published study suggests it could.

Jeffery Mondak and Damarys Canache, political science professors at the University of Illinois, analyzed personality data from more than 600,000 Americans, identified by state, who had responded to an online survey for another research study. They then matched that data with state-level measures of political culture, as identified by other, unrelated research.

The results were striking. ...

Warming climate may spread drying to a third of earth, says study

2014-03-31

Increasing heat is expected to extend dry conditions to far more farmland and cities by the end of the century than changes in rainfall alone, says a new study. Much of the concern about future drought under global warming has focused on rainfall projections, but higher evaporation rates may also play an important role as warmer temperatures wring more moisture from the soil, even in some places where rainfall is forecasted to increase, say the researchers.

The study is one of the first to use the latest climate simulations to model the effects of both changing rainfall ...

Black police officers good for entertainment only -- at least that's what movies tell us

2014-03-31

The presence of African-American police officers has been shown to increase the perceived legitimacy of police departments; however, their depiction in film may play a role in delegitimizing African-American officers in real life, both in the eyes of the general public and the African-American community.

In their recently released study, Sam Houston State University associate professor of criminal justice Howard Henderson and Indiana State University assistant professor of criminology and criminal justice Franklin T. Wilson found that African-American city police officers ...

Tropical Cyclone Hellen makes landfall in Madagascar

2014-03-31

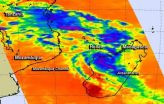

Tropical Cyclone Hellen made landfall in west central Madagascar as NASA's Aqua satellite passed overhead capturing temperature data on its towering thunderstorms.

When NASA's Aqua satellite passed over Madagascar on March 31 at 10:47 UTC/6:47 a.m. EDT and the Atmospheric Infrared Sounder or AIRS instrument aboard captured infrared data on Hellen. AIRS data showed powerful thunderstorms circling the center of circulation with cloud top temperatures in excess of -63F/-52C indicating they were high into the troposphere. Thunderstorms reaching those heights also have the ...

Urban gardeners may be unaware of how best to manage contaminants in soil

2014-03-31

Consuming foods grown in urban gardens may offer a variety of health benefits, but a lack of knowledge about the soil used for planting, could pose a health threat for both consumers and gardeners. In a new study from the Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future (CLF), researchers identified a range of factors and challenges related to the perceived risk of soil contamination among urban community gardeners and found a need for clear and concise information on how best to prevent and manage soil contamination. The results are featured online in PLOS ONE .

"While the ...

New functions for 'junk' DNA?

2014-03-31

DNA is the molecule that encodes the genetic instructions enabling a cell to produce the thousands of proteins it typically needs. The linear sequence of the A, T, C, and G bases in what is called coding DNA determines the particular protein that a short segment of DNA, known as a gene, will encode. But in many organisms, there is much more DNA in a cell than is needed to code for all the necessary proteins. This non-coding DNA was often referred to as "junk" DNA because it seemed unnecessary. But in retrospect, we did not yet understand the function of these seemingly ...

Hybrid vehicles more fuel efficient in India, China than in US

2014-03-31

What makes cities in India and China so frustrating to drive in—heavy traffic, aggressive driving style, few freeways—makes them ideal for saving fuel with hybrid vehicles, according to new research by scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy's Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab). In a pair of studies using real-world driving conditions, they found that hybrid cars are significantly more fuel-efficient in India and China than they are in the United States.

These findings could have an important impact in countries that are on the brink of experiencing ...

Behind the scenes of the IPCC report, with Stanford scientists

2014-03-31

In the summer of 2009, Stanford Professor Chris Field embarked on a task of urgent global importance.

Field had been tapped to assemble hundreds of climate scientists to dig through 12,000 scientific papers concerning the current impacts of climate change and its causes.

The team, Working Group II, would ultimately produce a 2,000-page report as part of a massive, three-part U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Fifth Assessment Report, which details a consensus view on the current state and fate of the world's climate.

The job would take nearly five ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Research alert: Long-read genome sequencing uncovers new autism gene variants

Genetic mapping of Baltic Sea herring important for sustainable fishing

In the ocean’s marine ‘snow,’ a scientist seeks clues to future climate

Understanding how “marine snow” acts as a carbon sink

In search of the room temperature superconductor: international team formulates research agenda

Index provides flu risk for each state

Altered brain networks in newborns with congenital heart disease

Can people distinguish between AI-generated and human speech?

New robotic microfluidic platform brings ai to lipid nanoparticle design

COSMOS trial results show daily multivitamin use may slow biological aging

Immune cells play key role in regulating eye pressure linked to glaucoma

National policy to remedy harms of race-based kidney function estimation associated with increased transplants for Black patients

Study finds teens spend nearly one-third of the school day on smartphones, with frequent checking linked to poorer attention

Team simulates a living cell that grows and divides

Study illuminates the experiences of people needing to seek abortion care out of state

Digital media use and child health and development

Seeking abortion care across state lines after the Dobbs decision

Smartphone use during school hours and association with cognitive control in youths ages 11 to 18

Maternal acetaminophen use and child neurodevelopment

Digital microsteps as scalable adjuncts for adults using GLP-1 receptor agonists

Researchers develop a biomimetic platform to enhance CAR T cell therapy against leukemia

Heart and metabolic risk factors more strongly linked to liver fibrosis in women than men, study finds

Governing with AI: a new AI implementation blueprint for policymakers

Recent pandemic viruses jumped to humans without prior adaptation, UC San Diego study finds

Exercise triggers memory-related brain 'ripples' in humans, researchers report

Increased risk of bullying in open-plan offices

Frequent scrolling affects perceptions of the work environment

Brain activity reveals how well we mentally size up others

Taiwanese and UK scientists identify FOXJ3 gene linked to drug-resistant focal epilepsy

Pregnancy complications impact women’s stress levels and cardiovascular risk long after delivery

[Press-News.org] Kinder, gentler med school: Students less depressed, learn moreCurriculum changes, resilience training lowers anxiety, SLU research shows