(Press-News.org) Nanostructures half the breadth of a DNA strand could improve the efficiency of light emitting diodes (LEDs), especially in the "green gap," a portion of the spectrum where LED efficiency plunges, simulations at the U.S. Department of Energy's National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC) have shown.

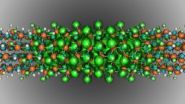

Using NERSC's Cray XC30 supercomputer "Edison," University of Michigan researchers Dylan Bayerl and Emmanouil Kioupakis found that the semiconductor indium nitride (InN), which typically emits infrared light, will emit green light if reduced to 1 nanometer-wide wires. Moreover, just by varying their sizes, these nanostructures could be tailored to emit different colors of light, which could lead to more natural-looking white lighting while avoiding some of the efficiency loss today's LEDs experience at high power.

"Our work suggests that indium nitride at the few-nanometer size range offers a promising approach to engineering efficient, visible light emission at tailored wavelengths," said Kioupakis.

Their results, published online in February as "Visible-Wavelength Polarized Light Emission with Small-Diameter InN Nanowires," and will be featured on the cover of the July issue of Nano Letters.

LEDs are semiconductor devices that emit light when an electrical current is applied. Today's LEDs are created as multilayered microchips. The outer layers are doped with elements that create an abundance of electrons on one layer and too few on the other. The missing electrons are called holes. When the chip is energized, the electrons and holes are pushed together, confined to the intermediate quantum-well layer where they are attracted to combine, shedding their excess energy (ideally) by emitting a photon of light.

At low power, nitride-based LEDs (most commonly used in white lighting) are very efficient, converting most of their energy into light. But turn the power up to levels that could light up a room and efficiency plummets, meaning a smaller fraction of electricity gets converted to light. This effect is especially pronounced in green LEDs, giving rise to the term "green gap."

Nanomaterials offer the tantalizing prospect of LEDs that can be "grown" in arrays of nanowires, dots or crystals. The resulting LEDs could not only be thin, flexible and high-resolution, but very efficient, as well.

"If you reduce the dimensions of a material to be about as wide as the atoms that make it up, then you get quantum confinement. The electrons are squeezed into a small region of space, increasing the bandgap energy," Kioupakis said. That means the photons emitted when electrons and holes combine are more energetic, producing shorter wavelengths of light.

The energy difference between an LED's electrons and holes, called the bandgap, determines the wavelength of the emitted light. The wider the bandgap, the shorter the wavelength of light. The bandgap for bulk InN is quite narrow, only 0.6 electron volts (eV), so it produces infrared light. In Bayerl and Kioupakis' simulated InN nanostructures, the calculated bandgap increased, leading to the prediction that green light would be produced with an energy of 2.3eV.

"If we can get green light by squeezing the electrons in this wire down to a nanometer, then we can get other colors by tailoring the width of the wire," said Kioupakis. A wider wire should yield yellow, orange or red. A narrower wire, indigo or violet.

That bodes well for creating more natural-looking light from LEDs. By mixing red, green and blue LEDs engineers can fine tune white light to warmer, more pleasing hues. This "direct" method isn't practical today because green LEDs are not as efficient as their blue and red counterparts. Instead, most white lighting today comes from blue LED light passed through a phosphor, a solution similar to fluorescent lighting and not a lot more efficient. Direct LED lights would not only be more efficient, but the color of light they produce could be dynamically tuned to suit the time of day or the task at hand.

Using pure InN, rather than layers of alloy nitride materials, would eliminate one factor that contributes to the inefficiency of green LEDs: nanoscale composition fluctuations in the alloys. These have been shown to significantly impact LED efficiency.

Also, using nanowires to make LEDs eliminates the "lattice mismatch" problem of layered devices. "When the two materials don't have the same spacing between their atoms and you grow one over the other, it strains the structure, which moves the holes and electrons further apart, making them less likely to recombine and emit light," said Kioupakis, who discovered this effect in previous research that also drew on NERSC resources. "In a nanowire made of a single material, you don't have this mismatch and so you can get better efficiency," he explained.

The researchers also suspect the nanowire's strong quantum confinement contributes to efficiency by squeezing the holes and electrons closer together, a subject for future research. "Bringing the electrons and holes closer together in the nanostructure increases their mutual attraction and increases the probability that they will recombine and emit light." Kioupakis said.

While this result points the way towards a promising avenue of exploration, the researchers emphasize that such small nanowires are difficult to synthesize. However, they suspect their findings can be generalized to other types of nanostructures, such as embedded InN nanocrystals, which have already been successfully synthesized in the few-nanometers range.

NERSC's newest flagship supercomputer (named "Edison" in honor of American inventor Thomas Edison) was instrumental in their research, said Bayerl. The system's thousands of compute cores and high memory-per-node allowed Bayerl to perform massively parallel calculations with many terabytes of data stored in RAM, which made the InN nanowire simulation feasible. "We also benefited greatly from the expert support of NERSC staff," said Bayerl. Burlen Loring of NERSC's Analytics Group created visualizations for the study, including the journal's cover image. The researchers also used the open-source BerkeleyGW code, developed by NERSC's Jack Deslippe.

INFORMATION:

This work was supported as part of the Center for Solar and Thermal Energy Conversion, an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science.

DOE's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

The National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC) is the primary high-performance computing facility for scientific research sponsored by the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science. Located at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, the NERSC Center serves more than 6,000 scientists at national laboratories and universities researching a wide range of problems in combustion, climate modeling, fusion energy, materials science, physics, chemistry, computational biology, and other disciplines. For more information, please visit http://www.nersc.gov

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory addresses the world's most urgent scientific challenges by advancing sustainable energy, protecting human health, creating new materials, and revealing the origin and fate of the universe. Founded in 1931, Berkeley Lab's scientific expertise has been recognized with 13 Nobel prizes. The University of California manages Berkeley Lab for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science. For more, visit http://www.lbl.gov.

To bridge LEDs' green gap, scientists think small... really small

Nanostructures half a DNA strand-wide show promise for efficient LEDs

2014-04-04

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Disease-free survival estimates for ovarian cancer improve over time

2014-04-04

SAN DIEGO, April 4, 2014 – The probability of staying disease-free improves dramatically for ovarian cancer patients who already have been disease-free for a period of time, and time elapsed since remission should be taken into account when making follow-up care decisions, according to a study led by researchers at the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute (UPCI), a partner with UPMC CancerCenter. The findings will be presented Wednesday at the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) Annual Meeting 2014.

A patient's prognosis traditionally is determined when ...

A new species of horseshoe worm discovered in Japan after a 62 year gap

2014-04-04

The horseshoe worm is a worm-like marine invertebrate inhabiting both hard and soft substrates such as rock, bivalve shells, and sandy bottom. The name "horseshoe" refers to the U-shaped crown of tentacles which is called "lophophore." Horseshoe worms comprise a small phylum Phoronida, which contains only ten species decorating the bottom of the oceans.

The new species Phoronis emigi, the eleventh member of the group described in the open access journal ZooKeys, comes after a long 62 year gap of new discoveries in the phylum. It is unique in the number and arrangement ...

Recurrent head and neck tumors have gene mutations that could be vulnerable to cancer drug

2014-04-04

SAN DIEGO, April 4, 2014 – An examination of the genetic landscape of head and neck cancers indicates that while metastatic and primary tumor cells share similar mutations, recurrent disease is associated with gene alterations that could be exquisitely sensitive to an existing cancer drug. Researchers from the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute (UPCI) and Yale University School of Medicine will share their findings during a mini-symposium Sunday at the American Association for Cancer Research Annual Meeting 2014.

About 50 percent of patients diagnosed with head ...

Common breast cancer subtype may benefit from personalized treatment approach

2014-04-04

SAN DIEGO, April 4, 2014 – The second-most common type of breast cancer is a very different disease than the most common and appears to be a good candidate for a personalized approach to treatment, according to a multidisciplinary team led by scientists at the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute (UPCI), a partner with UPMC CancerCenter.

Invasive lobular carcinoma, characterized by a unique growth pattern in breast tissue that fails to form a lump, has distinct genetic markers which indicate drug therapies may provide benefits beyond those typically prescribed for ...

Plant-derived anti-cancer compounds explained at national conference

2014-04-04

SAN DIEGO, April 4, 2014 – Compounds derived from plant-based sources — including garlic, broccoli and medicine plants — confer protective effects against breast cancer, explain researchers at the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute (UPCI), partner with the UPMC CancerCenter.

In multiple presentations Sunday at the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) Annual Meeting 2014, UPCI scientists will update the cancer research community on their National Cancer Institute (NCI)-funded findings, including new discoveries about the mechanisms by which the plant-derived ...

Genetic testing beneficial in melanoma treatment

2014-04-04

SAN DIEGO, April 4, 2014 – Genetic screening of cancer can help doctors customize treatments so that patients with melanoma have the best chance of beating it, according to the results of a clinical trial by researchers at the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute (UPCI), a partner with UPMC CancerCenter.

The trial, funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), will be presented Monday at the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) Annual Meeting 2014. It showed that the cancer immune therapy drug ipilimumab appears most likely to prevent recurrence ...

Combining cell replication blocker with common cancer drug kills resistant tumor cells

2014-04-04

SAN DIEGO, April 4, 2014 – Researchers from the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute (UPCI), a partner with UPMC CancerCenter, have found that an agent that inhibits mitochondrial division can overcome tumor cell resistance to a commonly used cancer drug, and that the combination of the two induces rapid and synergistic cell death. Separately, neither had an effect. These findings will be presented Monday at the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research Annual Meeting 2014.

"In our earlier work, we found that blocking production of a protein called ...

International consortium discovers 2 genes that modulate risk of breast and ovarian cancer

2014-04-04

Today we know that women carrying BCRA1 and BCRA2 gene mutations have a 43% to 88% risk of developing from breast cancer before the age of 70. Taking critical decisions such as opting for preventive surgery when the risk bracket is so wide is not easy. Spanish National Cancer Research Centre (CNIO) researchers are conducting a study that will contribute towards giving every woman far more precise data about her personal risk of suffering from cancer.

The paper has been authored by 200 researchers from 55 research groups from around the world and describes two new genes ...

Screening reveals additional link between endometriosis and ovarian cancer

2014-04-04

SAN DIEGO, April 4, 2014 – Some women with endometriosis, a chronic inflammatory disease, are predisposed to ovarian cancer, and a genetic screening might someday help reveal which women are most at risk, according to a University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute (UPCI) study, in partnership with Magee-Womens Research Institute (MWRI).

Monday at the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) Annual Meeting 2014, UPCI and MWRI researchers will present the preliminary results of the first comprehensive immune gene profile exploring endometriosis and cancer.

"A small ...

Grandparents may worsen some moms' baby blues

2014-04-04

Does living with grandparents ease or worsen a mothers' baby blues? The answer may depend on the mother's marital status, a new study from Duke University suggests.

Married and single mothers suffer higher rates of depression when they live in multi-generational households in their baby's first year of life, the study found. But for moms who live with their romantic partners but aren't married, having one or more grandparents in the house is linked to lower rates of depression.

The pattern held true for rich, poor and middle class women. The findings varied by race, ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Billion-DKK grant for research in green transformation of the built environment

For solar power to truly provide affordable energy access, we need to deploy it better

Middle-aged men are most vulnerable to faster aging due to ‘forever chemicals’

Starving cancer: Nutrient deprivation effects on synovial sarcoma

Speaking from the heart: Study identifies key concerns of parenting with an early-onset cardiovascular condition

From the Late Bronze Age to today - Old Irish Goat carries 3,000 years of Irish history

Emerging class of antibiotics to tackle global tuberculosis crisis

Researchers create distortion-resistant energy materials to improve lithium-ion batteries

Scientists create the most detailed molecular map to date of the developing Down syndrome brain

Nutrient uptake gets to the root of roots

Aspirin not a quick fix for preventing bowel cancer

HPV vaccination provides “sustained protection” against cervical cancer

Many post-authorization studies fail to comply with public disclosure rules

GLP-1 drugs combined with healthy lifestyle habits linked with reduced cardiovascular risk among diabetes patients

Solved: New analysis of Apollo Moon samples finally settles debate about lunar magnetic field

University of Birmingham to host national computing center

Play nicely: Children who are not friends connect better through play when given a goal

Surviving the extreme temperatures of the climate crisis calls for a revolution in home and building design

The wild can be ‘death trap’ for rescued animals

New research: Nighttime road traffic noise stresses the heart and blood vessels

Meningococcal B vaccination does not reduce gonorrhoea, trial results show

AAO-HNSF awarded grant to advance age-friendly care in otolaryngology through national initiative

Eight years running: Newsweek names Mayo Clinic ‘World’s Best Hospital’

Coffee waste turned into clean air solution: researchers develop sustainable catalyst to remove toxic hydrogen sulfide

Scientists uncover how engineered biochar and microbes work together to boost plant-based cleanup of cadmium-polluted soils

Engineered biochar could unlock more effective and scalable solutions for soil and water pollution

Differing immune responses in infants may explain increased severity of RSV over SARS-CoV-2

The invisible hand of climate change: How extreme heat dictates who is born

Surprising culprit leads to chronic rejection of transplanted lungs, hearts

Study explains how ketogenic diets prevent seizures

[Press-News.org] To bridge LEDs' green gap, scientists think small... really smallNanostructures half a DNA strand-wide show promise for efficient LEDs