(Press-News.org) WASHINGTON D.C., April 8, 2014 -- Some 90 years ago, British polymath J.B.S. Haldane proposed that for every animal there is an optimal size -- one which allows it to make best use of its environment and the physical laws that govern its activities, whether hiding, hunting, hoofing or hibernating. Today, three researchers are asking whether there is a "right" size for another type of huge beast: the U.S. power grid.

David Newman, a physicist at the University of Alaska, believes that smaller grids would reduce the likelihood of severe outages, such as the 2003 Northeast blackout that cut power to 50 million people in the United States and Canada for up to two days.

Newman and co-authors Benjamin Carreras, of BACV Solutions in Oak Ridge, Tenn., and Ian Dobson of Iowa State University make their case in the journal Chaos, which is produced by AIP Publishing.

Their investigation began 20 years ago, when Newman and Carreras were studying why stable fusion plasmas turned unstable so quickly. They modeled the problem by comparing the plasma to a sandpile.

"Sandpiles are stable until you get to a certain height. Then you add one more grain and the whole thing starts to avalanche. This is because the pile's grains are already close to the critical angle where they will start rolling down the pile. All it takes is one grain to trigger a cascade," he explained.

While discussing a blackout, Newman and Carreras realized that their sandpile model might help explain grid behavior.

The Structure of the U.S. Power Grid

North America has three power grids, interconnected systems that transmit electricity from hundreds of power plants to millions of consumers. Each grid is huge, because the more power plants and power lines in a grid, the better it can even out local variations in the supply and demand or respond if some part of the grid goes down.

On the other hand, large grids are vulnerable to the rare but significant possibility of a grid-wide blackout like the one in 2003.

"The problem is that grids run close to the edge of their capacity because of economic pressures. Electric companies want to maximize profits, so they don't invest in more equipment than they need," Newman said.

On a hot days, when everyone's air conditioners are on, the grid runs near capacity. If a tree branch knocks down a power line, the grid is usually resilient enough to distribute extra power and make up the difference. But if the grid is already near its critical point and has no extra capacity, there is a small but significant chance that it can collapse like a sandpile.

This is vulnerable to cascading events comes from the fact that the grid's complexity evolved over time. It reflects the tension between economic pressures and government regulations to ensure reliability.

"Over time, the grid evolved in ways that are not pre-engineered," Newman said.

Backup Power Versus Blackout Risk

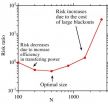

In their new paper, the researchers ask whether the grid has an optimal size, one large enough to share power efficiently but small enough to prevent enormous blackouts.

The team based its analysis on the Western United States grid, which has more than 16,000 nodes. Nodes include generators, substations, and transformers (which convert high-voltage electricity into low-voltage power for homes and business).

The model started by comparing one 1,000-bus grid with ten 100-bus networks. It then assessed how well the grids shared electricity in response to virtual outages.

"We found that for the best tradeoff between providing backup power and blackout risk, the optimal size was 500 to 700 nodes," Newman said.

Though grid wide blackouts are highly unlikely, they can dominate costs. They are very expensive and take longer to get things back under control. They also require more crews and resources, so utilities can help one another as they do in smaller blackouts.

In smaller grids, the blackouts are smaller and easier to fix because utilities can call for help from surrounding regions. Overall, small grid blackouts have a lower cost to society," Newman said.

The researchers believe their insights into sizing might apply to other complex, evolved networks like the Internet and financial markets.

"If we reduce the number of connected pieces, maybe we can reduce the societal cost of failures," Newman added.

INFORMATION:

The article, "Does size matter?" by B. A. Carreras, D. E. Newman, Ian Dobson appears in Chaos: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science (DOI: 10.1063/1.4868393). It will be published online on April 8, 2014. After that date, it may be accessed at: http://scitation.aip.org/content/aip/journal/chaos/24/2/10.1063/1.4868393

ABOUT THE JOURNAL

Chaos: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science is devoted to increasing the understanding of nonlinear phenomena and describing the manifestations in a manner comprehensible to researchers from a broad spectrum of disciplines. See: http://chaos.aip.org/

Is the power grid too big?

Right-sizing the grid could reduce blackout risk, according to new analysis in the journal 'Chaos'

2014-04-08

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Rice U. study: Creativity and innovation need to talk more

2014-04-08

HOUSTON – (April 8, 2014) – Creativity and innovation are not sufficiently integrated in either the business world or academic research, according to a new study by Rice University, the University of Edinburgh and Brunel University.

The findings are the result of the authors' review of the rapidly growing body of research into creativity and innovation in the workplace, with particular attention to the period from 2002 to 2013.

"There are many of us who study employee creativity and many of us who study innovation and idea implementation, but we don't talk to each ...

The surprising truth about obsessive-compulsive thinking

2014-04-08

Montreal, April 8, 2014 — People who check whether their hands are clean or imagine their house might be on fire are not alone. New research from Concordia University and 15 other universities worldwide shows that 94 per cent of people experience unwanted, intrusive thoughts, images and/or impulses.

The international study, which was co-authored by Concordia psychology professor Adam Radomsky and published in the Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders, examined people on six continents.

Radomsky and his colleagues found that the thoughts, images and ...

Where credit is due: How acknowledging expertise can help conservation efforts

2014-04-08

Scientists know that tapping into local expertise is key to conservation efforts aimed at protecting biodiversity – but researchers rarely give credit to these local experts. Now some scientists are saying that's a problem, both for the local experts and for the science itself.

To address the problem, a group of scientists is calling for conservation researchers to do a better job of publicly acknowledging the role of local experts and other non-scientists in conservation biology.

"For example, in the rainforests of the Yucatán, scientists couldn't even begin to do ...

Blocking DNA repair mechanisms could improve radiation therapy for deadly brain cancer

2014-04-08

DALLAS – April 8, 2014 – UT Southwestern Medical Center researchers have demonstrated in both cancer cell lines and in mice that blocking critical DNA repair mechanisms could improve the effectiveness of radiation therapy for highly fatal brain tumors called glioblastomas.

Radiation therapy causes double-strand breaks in DNA that must be repaired for tumors to keep growing. Scientists have long theorized that if they could find a way to block repairs from being made, they could prevent tumors from growing or at least slow down the growth, thereby extending patients' survival. ...

What songbirds tell us about how we learn

2014-04-08

This news release is available in French. When you throw a wild pitch or sing a flat note, it could be that your basal ganglia made you do it. This area in the middle of the brain is involved in motor control and learning. And one reason for that errant toss or off-key note may be that your brain prompted you to vary your behavior to help you learn, from trial-and-error, to perform better.

But how does the brain do this, how does it cause you to vary your behavior?

Along with researchers from the University of California, San Francisco, Indian Institute of Science ...

NASA satellite sees Tropical Depression Peipah approaching Philippines

2014-04-08

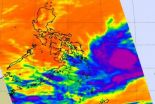

As Tropical Depression Peipah continues moving toward the central Philippines, NASA's Aqua satellite passed overhead and took an infrared look at the cloud top temperatures for clues about its strength.

On April 8 at 05:11 UTC/1:11 a.m. EDT/11 p.m. Manila local time, the Atmospheric Infrared Sounder instrument known as AIRS gathered infrared data on Tropical Depression Peipah. AIRS is one of the instruments that flies aboard NASA's Aqua satellite. The AIRS data showed thunderstorms with very cold cloud-top temperatures surrounded the center of the low-level circulation ...

Intranasal ketamine confers rapid antidepressant effect in depression

2014-04-08

A research team from the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai published the first controlled evidence showing that an intranasal ketamine spray conferred an unusually rapid antidepressant effect –within 24 hours—and was well tolerated in patients with treatment-resistant major depressive disorder. This is the first study to show benefits with an intranasal formulation of ketamine. Results from the study were published online in the peer-reviewed journal Biological Psychiatry on April 2, 2014.

Of 18 patients completing two treatment days with ketamine or saline, eight ...

DNA modifications measured in blood signal related changes in the brain

2014-04-08

Johns Hopkins researchers say they have confirmed suspicions that DNA modifications found in the blood of mice exposed to high levels of stress hormone — and showing signs of anxiety — are directly related to changes found in their brain tissues.

The proof-of-concept study, reported online ahead of print in the June issue of Psychoneuroendocrinology, offers what the research team calls the first evidence that epigenetic changes that alter the way genes function without changing their underlying DNA sequence — and are detectable in blood — mirror alterations in brain tissue ...

New methodology to find out about yeast changes during wine fermentation

2014-04-08

This knowledge is of particular interest for producers, since changes in the grape directly affect the chemical composition of the must.

The thesis entitled "Estudios avanzados de la fisiología de levadura en condiciones de vinificación. Bases para el desarrollo de un modelo predictivo" [Advanced studies into yeast physiology in vinification conditions. Bases for developing a forecasting model] is part of the Demeter project. This project seeks to study and find out the effects of climate change on viticultural and oenological activities, and to come up with new strategies ...

From learning in infancy to planning ahead in adulthood: Sleep's vital role for memory

2014-04-08

Boston - April 8, 2014 - Babies and young children make giant developmental leaps all of the time. Sometimes, it seems, even overnight they figure out how to recognize certain shapes or what the word "no" means no matter who says it. It turns out that making those leaps could be a nap away: New research finds that infants who nap are better able to apply lessons learned to new skills, while preschoolers are better able to retain learned knowledge after napping.

"Sleep plays a crucial role in learning from early in development," says Rebecca Gómez of the University of ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Do prostate cancer drugs interact with certain anticoagulants to increase bleeding and clotting risks?

Many patients want to talk about their faith. Neurologists often don't know how.

AI disclosure labels may do more harm than good

The ultra-high-energy neutrino may have begun its journey in blazars

Doubling of new prescriptions for ADHD medications among adults since start of COVID-19 pandemic

“Peculiar” ancient ancestor of the crocodile started life on four legs in adolescence before it began walking on two

AI can predict risk of serious heart disease from mammograms

New ultra-low-cost technique could slash the price of soft robotics

Increased connectivity in early Alzheimer’s is lowered by cancer drug in the lab

Study highlights stroke risk linked to recreational drugs, including among young users

Modeling brain aging and resilience over the lifespan reveals new individual factors

ESC launches guidelines for patients to empower women with cardiovascular disease to make informed pregnancy health decisions

Towards tailor-made heat expansion-free materials for precision technology

New research delves into the potential for AI to improve radiology workflows and healthcare delivery

Rice selected to lead US Space Force Strategic Technology Institute 4

A new clue to how the body detects physical force

Climate projections warn 20% of Colombia’s cocoa-growing areas could be lost by 2050, but adaptation options remain

New poll: American Heart Association most trusted public health source after personal physician

New ethanol-assisted catalyst design dramatically improves low-temperature nitrogen oxide removal

New review highlights overlooked role of soil erosion in the global nitrogen cycle

Biochar type shapes how water moves through phosphorus rich vegetable soils

Why does the body deem some foods safe and others unsafe?

Report examines cancer care access for Native patients

New book examines how COVID-19 crisis entrenched inequality for women around the world

Evolved robots are born to run and refuse to die

Study finds shared genetic roots of MS across diverse ancestries

Endocrine Society elects Wu as 2027-2028 President

Broad pay ranges in job postings linked to fewer female applicants

How to make magnets act like graphene

The hidden cost of ‘bullshit’ corporate speak

[Press-News.org] Is the power grid too big?Right-sizing the grid could reduce blackout risk, according to new analysis in the journal 'Chaos'