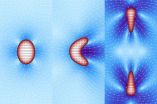

(Press-News.org) Droplets of filamentous material enclosed in a lipid membrane: these are the models of a "simplified" cell used by the SISSA physicists Luca Giomi and Antonio DeSimone, who simulated the spontaneous emergence of cell motility and division - that is, features of living material - in inanimate "objects". The research is one of the cover stories of the April 10th online issue of the journal Physical Review Letters.

Giomi and DeSimone's artificial cells are in fact computer models that mimic some of the physical properties of the materials making up the inner content and outer membrane of cells.

The two researchers varied some of the parameters of the materials, recording what happened: "our 'cells' are a 'bare bones' representation of a biological cell, which normally contains microtubules, elongated proteins enclosed in an essentially lipid cell membrane", explains Giomi, first author of the study. "The filaments contained in the 'cytoplasm' of our cells slide over one another exerting a force that we can control".

The force exerted by the filaments is the variable that competes with another force, the surface tension that keeps the membrane surrounding the droplet from collapsing. The generates a flow in the fluid surrounding the droplet, which in turn is propelled by such self-generated flow. When the flow becomes very strong, the droplet deforms to the point of dividing. "When the force of the flow prevails over the force that keeps the membrane together we have cellular division", explains DeSimone, director of the SISSA mathLab, SISSA's mathematical modelling and scientific computing laboratory.

"We showed that by acting on a single physical parameter in a very simple model we can reproduce similar effects to those obtained with experimental observations" continues DeSimone. Empirical observations on microtubule specimens have shown that these also move outside the cell environment, in a manner proportional to the energy they have (derived from ATP, the cell "fuel"). "Similarly, our droplets, fuelled by their 'inner' energy alone – without forces acting from the outside – are able to move and even divide".

More in detail ...

"Acquiring motility and the ability to divide is a fundamental step for life and, according to our simulations, the laws governing these phenomena could be very simple. Observations like ours can prepare the way for the creation of functioning artificial cells, and not only", comments Giomi. "Our work is also useful for understanding the transition from non-living to living matter on our planet. The development of the early forms of life, in other words."

Chemists and biologists who study the origin of life don't have access to cells that are sufficiently simple to be observed directly. "Even the simplest organism existing today has undergone billions of years of evolution", explains Giomi, "and will always contain fairly complex structures. Starting from schematic organisms as we do is like turning the clock back to when the first rudimentary living beings made their first appearance. We are currently starting studies to understand how cell metabolism emerged".

INFORMATION:

VIDEO: Artificial cell simulation (courtesy of Physical Review Letters) - http://goo.gl/vLDcbB

At the origin of cell division

The features of living matter emerge from inanimate matter

2014-04-16

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

EU must take urgent action on invasive species

2014-04-16

The EU must take urgent action to halt the spread of invasive species that are threatening native plants and animals across Europe, according to a scientist from Queen's University Belfast.

The threats posed by these species cost an estimated €12 billion each year across Europe. Professor Jaimie Dick, from the Institute for Global Food Security at Queen's School of Biological Sciences, is calling on the EU to commit long-term investment in a European-wide strategy to manage the problem.

Invasive species are considered to be among the major threats to native biodiversity ...

Expect changes in appetite, taste of food after weight loss surgery

2014-04-16

Changes in appetite, taste and smell are par for the course for people who have undergone Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery during which one's stomach is made smaller and small intestines shortened. These sensory changes are not all negative, and could lead to more weight loss among patients, says Lisa Graham, lead author of a study by researchers from Leicester Royal Infirmary in the UK. Their findings, published in Springer's journal Obesity Surgery showed that after gastric bypass surgery, patients frequently report sensory changes.

Graham and her colleagues say their ...

Fish exposed to antidepressants exhibit altered behavioral changes

2014-04-16

Amsterdam, April 16, 2014 - Fish exposed to the antidepressant Fluoxetine, an active ingredient in prescription drugs such as Prozac, exhibited a range of altered mating behaviours, repetitive behaviour and aggression towards female fish, according to new research published on in the latest special issue of Aquatic Toxicology: Antidepressants in the Aquatic Environment.

The authors of the study set up a series of experiments exposing a freshwater fish (Fathead Minnow) to a range of Prozac concentrations. Following exposure for 4 weeks the authors observed and recorded ...

Study: The trials of the Cherokee were reflected in their skulls

2014-04-16

Researchers from North Carolina State University and the University of Tennessee have found that environmental stressors – from the Trail of Tears to the Civil War – led to significant changes in the shape of skulls in the eastern and western bands of the Cherokee people. The findings highlight the role of environmental factors in shaping our physical characteristics.

"We wanted to look at these historically important events and further our understanding of the tangible human impacts they had on the Cherokee people," says Dr. Ann Ross, a professor of anthropology at NC ...

Progress in understanding immune response in severe schistosomiasis

2014-04-16

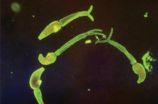

BOSTON (April 16, 2014) —Researchers at the Sackler School of Graduate Biomedical Sciences at Tufts and Tufts University School of Medicine (TUSM) have uncovered a mechanism that may help explain the severe forms of schistosomiasis, or snail fever, which is caused by schistosome worms and is one of the most prevalent parasitic diseases in the world. The study in mice, published online in The Journal of Immunology, may also offer targets for intervention and amelioration of the disease.

Schistosomiasis makes some people very sick whereas others tolerate it relatively well, ...

Floating nuclear plants could ride out tsunamis

2014-04-16

CAMBRIDGE, Mass-- When an earthquake and tsunami struck the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant complex in 2011, neither the quake nor the inundation caused the ensuing contamination. Rather, it was the aftereffects — specifically, the lack of cooling for the reactor cores, due to a shutdown of all power at the station — that caused most of the harm.

A new design for nuclear plants built on floating platforms, modeled after those used for offshore oil drilling, could help avoid such consequences in the future. Such floating plants would be designed to be automatically cooled ...

Bristol academics invited to speak at major 5G summit

2014-04-16

For more than 20 years academics from the University of Bristol have played a key role in the development of wireless communications. In particular, they have contributed to the development of today's Wi-Fi and cellular standards. Two Bristol engineers, who are leaders in this field, have been invited to a meeting of technology leaders to discuss the future of wireless communications. The first "Brooklyn 5G Summit" will be held next week [April 23-25] in New York, USA.

Andrew Nix, Professor of Wireless Communication Systems and Mark Beach, Professor of Radio Systems ...

Researchers question emergency water treatment guidelines

2014-04-16

The Environmental Protection Agency's (EPA's) recommendations for treating water after a natural disaster or other emergencies call for more chlorine bleach than is necessary to kill disease-causing pathogens and are often impractical to carry out, a new study has found. The authors of the report, which appears in the ACS journal Environmental Science & Technology, suggest that the agency review and revise its guidelines.

Daniele Lantagne, who was at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) at the time of the study and is now at Tufts University, and colleagues ...

Relieving electric vehicle range anxiety with improved batteries

2014-04-16

RICHLAND, Wash. – Electric vehicles could travel farther and more renewable energy could be stored with lithium-sulfur batteries that use a unique powdery nanomaterial.

Researchers added the powder, a kind of nanomaterial called a metal organic framework, to the battery's cathode to capture problematic polysulfides that usually cause lithium-sulfur batteries to fail after a few charges. A paper describing the material and its performance was published online April 4 in the American Chemical Society journal Nano Letters.

"Lithium-sulfur batteries have the potential to ...

Breakthrough points to new drugs from nature

2014-04-16

Researchers at Griffith University's Eskitis Institute have developed a new technique for discovering natural compounds which could form the basis of novel therapeutic drugs.

The corresponding author, Professor Ronald Quinn AM said testing the new process on a marine sponge had delivered not only confirmation that the system is effective, but also a potential lead in the fight against Parkinson's disease.

"We have found a new screening method which allows us to identify novel molecules drawn from nature to test for biological activity," Professor Quinn said.

"As it ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Kidney cancer study finds belzutifan plus pembrolizumab post-surgery helps patients at high risk for relapse stay cancer-free longer

Alkali cation effects in electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction

Test platforms for charging wireless cars now fit on a bench

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

Yes! The role of YAP and CTGF as potential therapeutic targets for preventing severe liver disease

Pancreatic cancer may begin hiding from the immune system earlier than we thought

[Press-News.org] At the origin of cell divisionThe features of living matter emerge from inanimate matter