(Press-News.org) Nanoparticles have been heralded as a potential "disruptive technology" in biomedicine, a versatile platform that could supplant conventional technologies, both as drug delivery vehicles and diagnostic tools.

First, however, researchers must demonstrate the properly timed disintegration of these extremely small structures, a process essential for their performance and their ability to be safely cleared out of a patient's body after their job is done. A new study presents a unique method to directly measure nanoparticle degradation in real time within biological environments.

"Nanoparticles are made with very diverse designs and properties, but all of them need to be eventually eliminated from the body after they complete their task," said cardiology researcher Michael Chorny, Ph.D., of The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP). "We offer a new method to analyze and characterize nanoparticle disassembly, as a necessary step in translating nanoparticles into clinical use."

Chorny and colleagues described this novel methodology in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, published online March 3, 2014, and in the journal's March 18 print issue.

The CHOP team has long investigated biodegradable nanoparticles for medical applications. With diameters ranging from a few tens to a few hundreds of nanometers, these particles are 10 to 1000 times smaller than red blood cells (a nanometer is one millionth of a millimeter). One major challenge is to continuously monitor the fate of nanoparticles in model biological settings and in living cells without disrupting cell functions.

"Accurately measuring nanoparticle disassembly in real time directly in media of interest, such as the interior of a living cell or other types of complex biological milieu, is challenging. Our goal here was to develop such a noninvasive method providing unbiased results," said Chorny. "These results will help researchers to customize nanoparticle formulations for specific therapeutic and diagnostic applications."

The study team used a physical phenomenon called Förster resonance energy transfer, or FRET, as a sort of molecular ruler to measure the distance between the components of their particles.

For this, the researchers labelled their formulations with fluorescent probes exhibiting the radiationless transfer of energy, i.e., FRET, when located within the same particle. This process results in a special pattern of fluorescence, a "fingerprint" of physically intact particles, which gradually disappears as particle disassembly proceeds. This change in the nanoparticle fluorescent properties can be monitored directly without separating the particles from their environment, allowing for undistorted, continuous measurements of their integrity.

"The molecules must be very close together, just several nanometers apart, for the energy transfer to take place," said Chorny. "The changes in the fluorescence patterns sensitively reflect the kinetics of nanoparticle disassembly. Based on these results, we can improve the particle design in order to make them safer and more effective."

The rate of disassembly is highly relevant to specific potential applications. For instance, some nanoparticles might carry a drug intended for quick action, while others should keep the drug protected and released in a controlled fashion over time. Tailoring formulation properties for these tasks may require carefully adjusting the time frame of the nanoparticle disassembly. This is where this technique can become a valuable tool, greatly facilitating the optimization process

In the current study, the scientists analyzed how nanoparticles disintegrated both in liquid and semi-liquid media, and in vascular cells simulating the fate of particles used to deliver therapy to injured blood vessels. "We found that disassembly is likely to occur more rapidly early in the vessel healing process and slow down later. This may have implications for the design of nanoparticles intended for targeted drug, gene or cell therapy of vascular disease," said Chorny.

Chorny and colleagues have long studied using nanoparticles formulated as carriers delivering antiproliferative drugs and biotherapeutics to blood vessels subject to dangerous restenosis (re-blockage). Many of these studies, in the Cardiology Research laboratory of CHOP co-author Robert J. Levy, M.D., use external magnetic fields to guide iron oxide-impregnated nanoparticles to metallic arterial stents, narrow scaffolds implanted within blood vessels.

The current research, said Chorny, while immediately relevant to restenosis therapy and magnetically guided delivery, has much broader potential applications. "Nanoparticles could be formulated with contrast agents for diagnostic imaging, or could deliver anticancer drugs to a tumor," he said. "Our measuring tool can help researchers to develop and optimize their nanomedicine formulations for a range of medical uses."

INFORMATION:

This research received support from the National Institutes of Health (grants HL007915 and HL111118), the American Heart Association, the Foerderer Fund, Erin's Fund, the Kibel Foundation, and the William J. Rashkind Endowment of The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. Chorny's co-authors, all from CHOP, were Jillian E. Tengood, Ph.D., Ivan S. Alferiev, Ph.D., Kehan Zhang, Ilia Fishbein, M.D., Ph.D., and Robert J. Levy, M.D.

"Real-time analysis of composite magnetic nanoparticle disassembly in vascular cells and biomimetic media," Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, published ahead of print, March 3, 2014, in March 18, 2014 print issue. 27, 2014. http://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1324104111

About The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia: The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia was founded in 1855 as the nation's first pediatric hospital. Through its long-standing commitment to providing exceptional patient care, training new generations of pediatric healthcare professionals and pioneering major research initiatives, Children's Hospital has fostered many discoveries that have benefited children worldwide. Its pediatric research program receives the highest amount of National Institutes of Health funding among all U.S. children's hospitals. In addition, its unique family-centered care and public service programs have brought the 535-bed hospital recognition as a leading advocate for children and adolescents. For more information, visit http://www.chop.edu.

Fluorescent-based tool reveals how medical nanoparticles biodegrade in real time

May inform development of versatile drug carriers for therapeutic uses in patients

2014-04-28

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

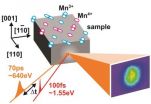

A glassy look for manganites

2014-04-28

Manganites – compounds of manganese oxides - show great promise as "go-to" materials for future electronic devices because of their ability to instantly switch from an electrical insulator to a conductor under a wide variety of external stimuli, including magnetic fields, photo-excitations and vibrational excitations. This ultrafast switching arises from the many different ways in which the electrons and electron-spins in a manganite may organize or re-organize in response to such external stimuli. Understanding the physics behind these responses is crucial for the future ...

Ozone levels drop 20 percent with switch from ethanol to gasoline

2014-04-28

A Northwestern University study by an economist and a chemist reports that when fuel prices drove residents of São Paulo, Brazil, to mostly switch from ethanol to gasoline in their flexible-fuel vehicles, local ozone levels dropped 20 percent. At the same time, nitric oxide and carbon monoxide concentrations tended to go up.

The four-year study is the first real-world trial looking at the effects of human behavior at the pump on urban air pollution. This empirical analysis of atmospheric pollutants, traffic congestion, consumer choice of fuel and meteorological conditions ...

Risk of cesarean delivery 12 percent lower with labor induction

2014-04-28

The risk of a cesarean delivery was 12% lower in women whose labour was induced compared with women who were managed with a "wait-and-see" approach (expectant management), according to a research paper published in CMAJ (Canadian Medical Association Journal).

Labour is induced in about 20% of all births for a variety of reasons such as preeclampsia, diabetes, preterm rupture of the membranes, overdue pregnancy and fetal distress. Induction is often thought to be associated with increased risk of cesarean deliveries despite evidence indicating a lower risk. However, much ...

Catastrophic thoughts about the future linked to suicidal patients

2014-04-28

Suicide has been on the increase recently in the United States, currently accounting for almost 40,000 deaths a year. A new study shows that one successful effort to avoid suicide attempts would be to focus on correcting the distorted, catastrophic thoughts about the future that are held by many who try to kill themselves. Such thoughts are unique and characteristic to those who attempt suicide, says Shari Jager-Hyman of the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine in the US. Jager-Hyman led a study, published in Springer's journal Cognitive Therapy and ...

Identification of genetic mutations involved in human blood diseases

2014-04-28

A study published today in Nature Genetics has revealed mutations that could have a major impact on the future diagnosis and treatment of many human diseases. Through an international collaboration, researchers at the Montreal Heart Institute (MHI) were able to identify a dozen mutations in the human genome that are involved in significant changes in complete blood counts and that explain the onset of sometimes severe biological disorders.

The number of red and white blood cells and platelets in the blood is an important clinical marker, as it helps doctors detect many ...

Stanford scientists create circuit board modeled on the human brain

2014-04-28

The Neurogrid circuit board can simulate orders of magnitude more neurons and synapses than other brain mimics on the power it takes to run a tablet computer.

Stanford scientists have developed a new circuit board modeled on the human brain, possibly opening up new frontiers in robotics and computing.

For all their sophistication, computers pale in comparison to the brain. The modest cortex of the mouse, for instance, operates 9,000 times faster than a personal computer simulation of its functions.

Not only is the PC slower, it takes 40,000 times more power to run, ...

Using a foreign language changes moral decisions

2014-04-28

Would you sacrifice one person to save five? Such moral choices could depend on whether you are using a foreign language or your native tongue.

A new study from psychologists at the University of Chicago and Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona finds that people using a foreign language take a relatively utilitarian approach to moral dilemmas, making decisions based on assessments of what's best for the common good. That pattern holds even when the utilitarian choice would produce an emotionally difficult outcome, such as sacrificing one life so others could live.

"This ...

UEA research shows bacteria combat dangerous gas leaks

2014-04-28

Bacteria could mop up naturally-occurring and man-made leaks of natural gases before they are released into the atmosphere and cause global warming - according to new research from the University of East Anglia.

Findings published today in the journal Nature shows how a single bacterial strain (Methylocella silvestris) found in soil and other environments around the world can grow on both the methane and propane found in natural gas.

It was originally thought that the ability to metabolize methane and other gaseous alkanes such as propane was carried out by different ...

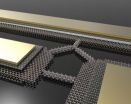

How to create nanowires only 3 atoms wide with an electron beam

2014-04-28

Junhao Lin, a Vanderbilt University Ph.D. student and visiting scientist at Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL), has found a way to use a finely focused beam of electrons to create some of the smallest wires ever made. The flexible metallic wires are only three atoms wide: One thousandth the width of the microscopic wires used to connect the transistors in today's integrated circuits.

Lin's achievement is described in an article published online on April 28 by the journal Nature Nanotechnology. According to his advisor Sokrates Pantelides, University Distinguished Professor ...

First disease-specific human embryonic stem cell line by nuclear transfer

2014-04-28

NEW YORK, NY (April 28, 2014) – Using somatic cell nuclear transfer, a team of scientists led by Dr. Dieter Egli at the New York Stem Cell Foundation (NYSCF) Research Institute and Dr. Mark Sauer at Columbia University Medical Center has created the first disease-specific embryonic stem cell line with two sets of chromosomes.

As reported today in Nature, the scientists derived embryonic stem cells by adding the nuclei of adult skin cells to unfertilized donor oocytes using a process called somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT). Embryonic stem cells were created from one ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

A biological material that becomes stronger when wet could replace plastics

Glacial feast: Seals caught closer to glaciers had fuller stomachs

Get the picture? High-tech, low-cost lens focuses on global consumer markets

Antimicrobial resistance in foodborne bacteria remains a public health concern in Europe

Safer batteries for storing energy at massive scale

How can you rescue a “kidnapped” robot? A new AI system helps the robot regain its sense of location in dynamic, ever-changing environments

Brainwaves of mothers and children synchronize when playing together – even in an acquired language

A holiday to better recovery

Cal Poly’s fifth Climate Solutions Now conference to take place Feb. 23-27

Mask-wearing during COVID-19 linked to reduced air pollution–triggered heart attack risk in Japan

Achieving cross-coupling reactions of fatty amide reduction radicals via iridium-photorelay catalysis and other strategies

Shorter may be sweeter: Study finds 15-second health ads can curb junk food cravings

Family relationships identified in Stone Age graves on Gotland

Effectiveness of exercise to ease osteoarthritis symptoms likely minimal and transient

Cost of copper must rise double to meet basic copper needs

A gel for wounds that won’t heal

Iron, carbon, and the art of toxic cleanup

Organic soil amendments work together to help sandy soils hold water longer, study finds

Hidden carbon in mangrove soils may play a larger role in climate regulation than previously thought

Weight-loss wonder pills prompt scrutiny of key ingredient

Nonprofit leader Diane Dodge to receive 2026 Penn Nursing Renfield Foundation Award for Global Women’s Health

Maternal smoking during pregnancy may be linked to higher blood pressure in children, NIH study finds

New Lund model aims to shorten the path to life-saving cell and gene therapies

Researchers create ultra-stretchable, liquid-repellent materials via laser ablation

Combining AI with OCT shows potential for detecting lipid-rich plaques in coronary arteries

SeaCast revolutionizes Mediterranean Sea forecasting with AI-powered speed and accuracy

JMIR Publications’ JMIR Bioinformatics and Biotechnology invites submissions on Bridging Data, AI, and Innovation to Transform Health

Honey bees navigate more precisely than previously thought

Air pollution may directly contribute to Alzheimer’s disease

Study finds early imaging after pediatric UTIs may do more harm than good

[Press-News.org] Fluorescent-based tool reveals how medical nanoparticles biodegrade in real timeMay inform development of versatile drug carriers for therapeutic uses in patients