(Press-News.org) A study led by Michael Worobey at the University of Arizona in Tucson provides the most conclusive answers yet to two of the world's foremost biomedical mysteries of the past century: the origin of the 1918 pandemic flu virus and its unusual severity, which resulted in a death toll of approximately 50 million people.

Worobey's paper on the flu, to be published in the early edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) on April 28, not only sheds light on the devastating 1918 pandemic, but also suggests that the types of flu viruses to which people were exposed during childhood may predict how susceptible they are to future strains, which could inform vaccination strategies and pandemic prevention and preparedness.

"Ever since the great flu pandemic of 1918, it has been a mystery where that virus came from and why it was so severe, and in particular, why it killed young adults in the prime of life," said Worobey, a professor in the UA Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. "It has been a huge question what the ingredients for that calamity were, and whether we should expect the same thing to happen tomorrow, or whether there was something special about that situation."

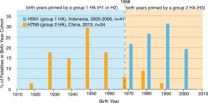

Worobey and his colleagues developed an unprecedentedly accurate molecular clock approach and used it to reconstruct the origins of the 1918 pandemic H1N1 influenza A virus (IAV), the classical swine H1N1 influenza virus and the post-pandemic seasonal H1N1 lineage that circulated from 1918 until 1957. Surprisingly, they found no evidence for either of the prevailing hypotheses for the origin of the 1918 virus – that it jumped directly from birds or involved the swapping of genes between existing human and swine influenza strains. Instead, the researchers inferred that the pandemic virus arose shortly before 1918 upon the acquisition of genetic material from a bird flu virus by an already circulating human H1 virus – one that had likely entered the human population 10-15 years prior to 1918.

"It sounds like a modest little detail, but it may be the missing piece of the puzzle," Worobey said. "Once you have that clue, many other lines of evidence that have been around since 1918 fall into place."

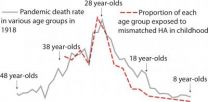

If these individuals had been already been exposed to an H1 virus, it could explain why they experienced much lower rates of death in 1918 than those who died in greatest numbers, a cohort centered on those about 29 years of age in 1918.

IAV typically kills primarily infants and the elderly, but the pandemic virus caused extensive mortality in those ages 20 to 40, primarily from secondary bacterial infections, especially pneumonia. The authors suggest that this is likely to be because many young adults born from about 1880 to 1900 were exposed during childhood to a putative H3N8 virus circulating in the population, which featured surface proteins distinct to both the major antigenic proteins of the H1N1 virus.

The authors compared the virus' genetic history with the types of antibodies present in people from different generations alive in 1918 and with death-by-birth-year patterns not only in 1918 but also in later years. The combined lines of evidence suggest that this small wedge of the population may have been uniquely susceptible to severe disease in 1918, whereas most individuals born earlier or later than between 1880 and 1900 would have had better protection against the 1918 H1N1 virus due to childhood exposure to N1 and/or H1-related antigens.

The authors speculate that long-term protection, for example the perplexingly low mortality in very elderly people in 1918 who may have been exposed in youth to an H1N1-like virus, might be mediated by immune responses to relatively slowly evolving regions of the viral HA protein.

"Imagine a soccer ball studded with lollipops," Worobey explained. "The candy part of the lollipop is the globular part of the HA protein, and that is by far the most potent part of the flu virus against which our immune system can make antibodies. If antibodies cover all the lollipop heads, the virus can't even infect you."

The part of the protein that represents the stem of the lollipop in this analogy is less exposed to the immune system's responses.

"Antibodies binding the HA stalk might not prevent infection altogether, but they can get in the way enough to prevent the virus from multiplying as much as it otherwise would, which protects you from severe disease and death," Worobey said.

"But a person with an antibody arsenal directed against the H3 protein would not have fared well when faced with flu viruses studded with H1 protein," Worobey said, "And we believe that that mismatch may have resulted in the heightened mortality in the age group that happened to be in their late 20s during the 1918 pandemic."

The authors note that childhood exposure to mismatched viral proteins may nevertheless have been better than nothing: isolated populations on islands where many individuals might have had no prior exposure to IAV before 1918 suffered mortality rates many times higher than the "H3N8" cohort of young adults worldwide.

The authors suggest that immunization strategies that mimic the often impressive protection provided by initial childhood exposure to influenza virus variants encountered later in life might dramatically reduce mortality due to both seasonal and novel IAV strains.

Worobey said the new perspective does not just apply to the pandemic of 1918, but might also explain patterns of seasonal flu mortality and the mysterious patterns of mortality from highly pathogenic avian origin H5N1. H5N1causes higher mortality rates in young people and H7N9 causes higher mortality in the elderly. In both cases, the more susceptible age groups were exposed initially, as children, to viruses with a mismatched HA, and may suffer severe consequences similar to young adults faced with a mismatched virus in 1918.

"What seems to be the decisive factor is prior immunity," Worobey said. "Our study takes a variety of observations that have been difficult to explain and reconciles and places them into a logical chain able to explain many patterns of influenza mortality over the last 200 years. What we need to do now is to attempt to validate these hypotheses and determine the exact mechanisms involved, then apply that knowledge directly to better prevent people from dying from seasonal flu and future pandemic strains."

INFORMATION:

The study, "The genesis and pathogenesis of the 1918 pandemic influenza A virus," was co-authored by Guan-Zhu Han at the UA Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and Andrew Rambaut at the Centre for Infection, Immunity and Evolution at the University of Edinburgh and the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Md.

Mystery of the pandemic flu virus of 1918 solved by University of Arizona researchers

University of Arizona researcher Michael Worobey and his team have discovered the key to understanding influenza pandemics may lie in previous flu exposure during childhood

2014-04-28

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Success really does breed success, unique online experiments find

2014-04-28

Success really does breed success – up to a point - found researchers from UCL and Stony Brook University, following a series of unique on-line experiments.

For decades, it has been observed that similar people experience divergent success trajectories, with some repeatedly succeeding and others repeatedly failing. Some suggest initial success can catalyse further achievements, creating a positive feedback loop, while others attribute a string of successes to inherent talent. To test these views the researchers conducted four experiments that measured the impact of experimental ...

How Brazilian cattle ranching policies can reduce deforestation

2014-04-28

Berkeley — There is a higher cost to steaks and hamburgers than what is reflected on the price tags at grocery stores and restaurants. Producing food – and beef, in particular – is a significant source of greenhouse gas emissions, which are projected to grow as rising incomes in emerging economies lead to greater demands for meat.

But an encouraging new study by researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, and international collaborators finds that policies to support sustainable cattle ranching practices in Brazil could put a big dent in the beef and food ...

Brazilian agricultural policy could cut global greenhouse gas emissions

2014-04-28

Brazil may be able to curb up to 26% of global greenhouse gas emissions from deforestation by encouraging the intensification of its cattle production, according to a new study from researchers at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) and international collaborators.

The study, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, showed that by subsidizing semi-intensive pasture-based cattle production or taxing conventional pastures Brazil may be able to deliver a substantial cut in global greenhouse gas emissions, even ...

Oxytocin promotes social behavior in infant rhesus monkeys

2014-04-28

The hormone oxytocin appears to increase social behaviors in newborn rhesus monkeys, according to a study by researchers at the National Institutes of Health, the University of Parma in Italy, and the University of Massachusetts Amherst. The findings indicate that oxytocin is a promising candidate for new treatments for developmental disorders affecting social skills and bonding.

Oxytocin, a hormone produced by the pituitary gland, is involved in labor and birth and in the production of breast milk. Studies have shown that oxytocin also plays a role in parental bonding, ...

Scientists identify antibodies against deadly emerging disease

2014-04-28

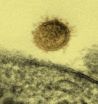

Scientists at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute have identified natural human antibodies against the virus that causes Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), a step toward developing treatments for the newly emerging and often-fatal disease.

Currently there is no vaccine or antiviral treatment for MERS, a severe respiratory disease with a mortality rate of more than 40 percent that was first reported in Saudi Arabia in 2012.

In laboratory studies reported in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), the researchers found that these "neutralizing" antibodies ...

Study: Tart cherry juice increases sleep time in adults with insomnia

2014-04-28

SAN DIEGO, Calif. April 28, 2014 – A morning and evening ritual of tart cherry juice may help you sleep better at night, suggests a new study presented today at the Experimental Biology 2014 meeting. Researchers from Louisiana State University found that drinking Montmorency tart cherry juice twice a day for two weeks helped increase sleep time by nearly 90 minutes among older adults with insomnia.

These findings were presented Monday, April 28, at the "Dietary Bioactive Components: Antioxidant and Anti-inflammatory Effects of Dietary Bioactive Components" section of ...

Decrease in large wildlife drives an increase in rodent-borne disease and risk to humans

2014-04-28

Populations of large wildlife are declining around the world, while zoonotic diseases (those transmitted from animals to humans) are on the rise. A team of Smithsonian scientists and colleagues have discovered a possible link between the two. They found that in East Africa, the loss of large wildlife directly correlated with a significant increase in rodents, which often carry disease-causing bacteria dangerous to humans. The team's research is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, April 28.

"Our study shows us that ecosystem health, wildlife ...

Smart home programming: Easy as 'if this, then that'

2014-04-28

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — The idea of a smart home sounds promising enough. Who doesn't want a house full of automated gadgets — from light switches to appliances to heating systems — that know exactly when to turn on, turn off, heat up or power down?

But in order for all those devices to do what they're supposed to do, they'll need to be programed — a task the average homeowner might not have the interest or the tech-savvy to perform. And nobody wants to call tech support just to turn on a light.

A group of computer science researchers from Brown and Carnegie ...

Satellite movie shows US tornado outbreak from space

2014-04-28

VIDEO:

This animation of NOAA's GOES-East satellite data shows the development and movement of the weather system that spawned tornadoes affecting seven central and southern US states on Apr. 27-28, 2014....

Click here for more information.

NASA has just released an animation of visible and infrared satellite data from NOAA's GOES-East satellite that shows the development and movement of the weather system that spawned tornadoes affecting seven central and southern U.S. states ...

NIH scientists establish monkey model of hantavirus disease

2014-04-28

WHAT: National Institutes of Health (NIH) researchers have developed an animal model of human hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (HPS) in rhesus macaques, an advance that may lead to treatments, vaccines and improved methods of diagnosing the disease. The study, conducted by researchers at NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

People become infected with hantaviruses by inhaling virus from the urine, droppings or saliva of infected rodents. This infection can progress to HPS, ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Scientists show how to predict world’s deadly scorpion hotspots

ASU researchers to lead AAAS panel on water insecurity in the United States

ASU professor Anne Stone to present at AAAS Conference in Phoenix on ancient origins of modern disease

Proposals for exploring viruses and skin as the next experimental quantum frontiers share US$30,000 science award

ASU researchers showcase scalable tech solutions for older adults living alone with cognitive decline at AAAS 2026

Scientists identify smooth regional trends in fruit fly survival strategies

Antipathy toward snakes? Your parents likely talked you into that at an early age

Sylvester Cancer Tip Sheet for Feb. 2026

Online exposure to medical misinformation concentrated among older adults

Telehealth improves access to genetic services for adult survivors of childhood cancers

Outdated mortality benchmarks risk missing early signs of famine and delay recognizing mass starvation

Newly discovered bacterium converts carbon dioxide into chemicals using electricity

Flipping and reversing mini-proteins could improve disease treatment

Scientists reveal major hidden source of atmospheric nitrogen pollution in fragile lake basin

Biochar emerges as a powerful tool for soil carbon neutrality and climate mitigation

Tiny cell messengers show big promise for safer protein and gene delivery

AMS releases statement regarding the decision to rescind EPA’s 2009 Endangerment Finding

Parents’ alcohol and drug use influences their children’s consumption, research shows

Modular assembly of chiral nitrogen-bridged rings achieved by palladium-catalyzed diastereoselective and enantioselective cascade cyclization reactions

Promoting civic engagement

AMS Science Preview: Hurricane slowdown, school snow days

Deforestation in the Amazon raises the surface temperature by 3 °C during the dry season

Model more accurately maps the impact of frost on corn crops

How did humans develop sharp vision? Lab-grown retinas show likely answer

Sour grapes? Taste, experience of sour foods depends on individual consumer

At AAAS, professor Krystal Tsosie argues the future of science must be Indigenous-led

From the lab to the living room: Decoding Parkinson’s patients movements in the real world

Research advances in porous materials, as highlighted in the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

Sally C. Morton, executive vice president of ASU Knowledge Enterprise, presents a bold and practical framework for moving research from discovery to real-world impact

Biochemical parameters in patients with diabetic nephropathy versus individuals with diabetes alone, non-diabetic nephropathy, and healthy controls

[Press-News.org] Mystery of the pandemic flu virus of 1918 solved by University of Arizona researchersUniversity of Arizona researcher Michael Worobey and his team have discovered the key to understanding influenza pandemics may lie in previous flu exposure during childhood