(Press-News.org) VIDEO:

Patterns of activation induced by listening to human speech move across brain hemispheres over a period of 300 milliseconds in these images, produced by combining data from EEG, MEG and...

Click here for more information.

How does the brain decide whether or not something is correct? When it comes to the processing of spoken language – particularly whether or not certain sound combinations are allowed in a language – the common theory has been that the brain applies a set of rules to determine whether combinations are permissible. Now the work of a Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) investigator and his team supports a different explanation – that the brain decides whether or not a combination is allowable based on words that are already known. The findings may lead to better understanding of how brain processes are disrupted in stroke patients with aphasia and also address theories about the overall operation of the brain.

"Our findings have implications for the idea that the brain acts as a computer, which would mean that it uses rules – the equivalent of software commands – to manipulate information. Instead it looks like at least some of the processes that cognitive psychologists and linguists have historically attributed to the application of rules may instead emerge from the association of speech sounds with words we already know," says David Gow, PhD, of the MGH Department of Neurology.

"Recognizing words is tricky – we have different accents and different, individual vocal tracts; so the way individuals pronounce particular words always sounds a little different," he explains. "The fact that listeners almost always get those words right is really bizarre, and figuring out why that happens is an engineering problem. To address that, we borrowed a lot of ideas from other fields and people to create powerful new tools to investigate, not which parts of the brain are activated when we interpret spoken sounds, but how those areas interact."

Human beings speak more than 6,000 distinct language, and each language allows some ways to combine speech sounds into sequences but prohibits others. Although individuals are not usually conscious of these restrictions, native speakers have a strong sense of whether or not a combination is acceptable.

"Most English speakers could accept "doke" as a reasonable English word, but not "lgef," Gow explains. "When we hear a word that does not sound reasonable, we often mishear or repeat it in a way that makes it sound more acceptable. For example, the English language does not permit words that begin with the sounds "sr-," but that combination is allowed in several languages including Russian. As a result, most English speakers pronounce the Sanskrit word 'sri' – as in the name of the island nation Sri Lanka – as 'shri,' a combination of sounds found in English words like shriek and shred."

VIDEO:

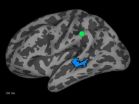

When recognizing combinations of speech sounds, a brain region that processes speech sounds (in blue), receives signals from areas involved in the representation of known words (green circles).

Click here for more information.

Gow's method of investigating how the human brain perceives and distinguishes among elements of spoken language combines electroencephalography (EEG), which records electrical brain activity; magnetoencephalograohy (MEG), which the measures subtle magnetic fields produced by brain activity, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which reveals brain structure. Data gathered with those technologies are then analyzed using Granger causality, a method developed to determine cause-and-effect relationships among economic events, along with a Kalman filter, a procedure used to navigate missiles and spacecraft by predicting where something will be in the future. The results are "movies" of brain activity showing not only where and when activity occurs but also how signals move across the brain on a millisecond-by-millisecond level, information no other research team has produced.

In a paper published earlier this year in the online journal PLOS One, Gow and his co-author Conrad Nied, now a PhD candidate at the University of Washington, described their investigation of how the neural processes involved in the interpretation of sound combinations differ depending on whether or not a combination would be permitted in the English language. Their goal was determining which of three potential mechanisms are actually involved in the way humans "repair" nonpermissible sound combinations – the application of rules regarding sound combinations, the frequency with which particular combinations have been encountered, or whether sound combinations occur in known words.

The study enrolled 10 adult American English speakers who listened to a series of recordings of spoken nonsense syllables that began with sounds ranging between "s" to "shl" – a combination not found at the beginning of English words – and indicated by means of a button push whether they heard an initial "s" or "sh." EEG and MEG readings were taken during the task, and the results were projected onto MR images taken separately. Analysis focused on 22 regions of interest where brain activation increased during the task, with particular attention to those regions' interactions with an area previously shown to play a role in identifying speech sounds.

While the results revealed complex patterns of interaction between the measured regions, the areas that had the greatest effect on regions that identify speech sounds were regions involved in the representation of words, not those responsible for rules. "We found that it's the areas of the brain involved in representing the sound of words, not sounds in isolation or abstract rules, that send back the important information. And the interesting thing is that the words you know give you the rules to follow. You want to put sounds together in a way that's easy for you to hear and to figure out what the other person is saying," explains Gow, who is a clinical instructor in Neurology at Harvard Medical School and a professor of Psychology at Salem State University.

Gow and his team are planning to investigate the same mechanisms in stroke patients who have trouble producing words, with the goal of understanding how language processing breaks down and perhaps may be restored, as well as to look at whether learning words with previously nonpermissible combinations changes activation in the brains of healthy volunteers. The study reported in the PLOS One paper was supported by National Institute of Deafness and Communicative Disorders grant R01 DC003108.

INFORMATION:

Massachusetts General Hospital, founded in 1811, is the original and largest teaching hospital of Harvard Medical School. The MGH conducts the largest hospital-based research program in the United States, with an annual research budget of more than $775 million and major research centers in AIDS, cardiovascular research, cancer, computational and integrative biology, cutaneous biology, human genetics, medical imaging, neurodegenerative disorders, regenerative medicine, reproductive biology, systems biology, transplantation biology and photomedicine.

In recognizing speech sounds, the brain does not work the way a computer does

Acceptable combinations determined by reference to known words, not application of abstract rules

2014-04-30

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Social media users need help to adjust to interface changes

2014-04-30

Social media companies that give users a greater sense of control can ease them into interface changes, as well as curb defections to competitors, according to researchers.

"Several studies have looked into how social media companies have failed," said Pamela Wisniewski, a post-doctoral scholar in information sciences and technology, Penn State. "What we need to think about is how social media companies can be more adaptive and how they can improve the longevity of their sites.

In a study of the reaction to the introduction of Facebook's Timeline interface between 2011 ...

Parents just as likely to use cell phones while driving, putting child passengers at risk

2014-04-30

Ann Arbor, Mich. — Despite their precious cargo, parents are no less likely to engage in driving distractions like cell phone use than drivers from the general population, according to a new University of Michigan study published in

Academic Pediatrics.

The study found that 90 percent of parent drivers said they engaged in at least one of the 10 distractions examined in the study while their child was a passenger and the vehicle was moving, says lead author Michelle L. Macy, M.D., M.S., an emergency medicine physician at the University of Michigan's C.S. Mott Children's ...

Study questions Neandertal inferiority to early modern humans

2014-04-30

The embargo has been lifted for the article, 'Neandertal Demise: An Archaeological Analysis of the Modern Human Superiority Complex.'

An analysis of the archaeological records of Neandertals and their modern human contemporaries has found that complex interbreeding and assimilation may have been responsible for Neandertal disappearance 40,000 years ago, in contrast to many current theories, according to results published April 30, 2014, in the open access journal PLOS ONE by Paola Villa from the University of Colorado Museum and Wil Roebroeks from Leiden University ...

Lymph node ultrasounds more accurate in obese breast cancer patients

2014-04-30

ROCHESTER, Minn. — Mayo Clinic research into whether ultrasounds to detect breast cancer in underarm lymph nodes are less effective in obese women has produced a surprising finding. Fat didn't obscure the images — and ultrasounds showing no suspicious lymph nodes actually proved more accurate in overweight and obese patients than in women with a normal body mass index, the study found. The research is among several Mayo studies presented at the American Society of Breast Surgeons annual meeting April 30-May 4 in Las Vegas.

Researchers studied 1,331 breast cancer patients ...

Surgeons and health care settings influence type of breast cancer surgery women undergo

2014-04-30

TORONTO, April 30, 2014 – Breast cancer is one of the few major illnesses for which physicians may not recommend a specific treatment option. North American women are more likely to opt for precautionary breast surgery when physicians don't specifically counsel against it, according to a new study.

The research, presented today at the American Society of Breast Surgeons Annual Meeting in Las Vegas, also demonstrates how clarity during consultations and the capability of clinical facilities also play important roles influencing a woman's breast cancer treatment choices.

There ...

Study: Women leaders perceived as effective as male counterparts

2014-04-30

WASHINGTON -- When it comes to being perceived as effective leaders, women are rated as highly as men, and sometimes higher - a finding that speaks to society's changing gender roles and the need for a different management style in today's globalized workplace, according to a meta-analysis published by the American Psychological Association.

"When all leadership contexts are considered, men and women do not differ in perceived leadership effectiveness," said lead researcher Samantha C. Paustian-Underdahl, PhD, of Florida International University. "As more women have ...

Flexible pressure-sensor film shows how much force a surface 'feels' -- in color

2014-04-30

A newly developed pressure sensor could help car manufacturers design safer automobiles and even help Little League players hold their bats with a better grip, scientists report. The study describing their high-resolution sensor, which can be painted onto surfaces or built into gloves, appears in the ACS journal Nano Letters.

Yadong Yin and colleagues explain that pressure is a part of our daily lives. We and the objects around us constantly exert pressure on surfaces, from a simple, light touch of a finger on a smartphone screen to the impact of a head-on car collision. ...

Sustainable barnacle-repelling paint could help the shipping industry and the environment

2014-04-30

Barnacles might seem like a given part of a seasoned ship's hull, but they're literally quite a drag and cause a ship to burn more fuel. To prevent these and other hangers-on from slowing ships down, scientists are developing a sustainable paint ingredient from plants that can repel clingy sea critters without killing them. The report appears in the ACS journal Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research.

Guillermo Blustein and colleagues explain that barnacles and other ocean creatures that stick to hulls create a cascade of problems. By increasing water resistance, ...

Capturing carbon to produce more oil: Climate solution or folly?

2014-04-30

Any method that leads to the production of more oil seems counter to the prevailing wisdom on climate change that says use of more greenhouse-gas-emitting fuel is detrimental. But there's one oil-recovery process that some say could be part of the climate change solution and now unites unlikely allies in industry, government and environmental groups, according to an article in Chemical & Engineering News (C&EN), the weekly news magazine of the American Chemical Society.

Jeff Johnson, a senior correspondent at C&EN, explains that a process called enhanced oil recovery ...

Faster dental treatment with new photoactive molecule

2014-04-30

In modern dentistry, amalgam fillings have become unpopular. Instead, white composite materials are more commonly used, which at first glance can hardly be distinguished from the tooth. The majority of these composites are based on photoactive materials that harden when they are exposed to light. But as the light does not penetrate very deeply into the material, the patients often have to endure a cumbersome procedure in which the fillings are applied and hardened in several steps. The Vienna University of Technology in collaboration with the company Ivoclar Vivadent have ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

Yes! The role of YAP and CTGF as potential therapeutic targets for preventing severe liver disease

Pancreatic cancer may begin hiding from the immune system earlier than we thought

Robotic wing inspired by nature delivers leap in underwater stability

A clinical reveals that aniridia causes a progressive loss of corneal sensitivity

Fossil amber reveals the secret lives of Cretaceous ants

Predicting extreme rainfall through novel spatial modeling

The Lancet: First-ever in-utero stem cell therapy for fetal spina bifida repair is safe, study finds

Nanoplastics can interact with Salmonella to affect food safety, study shows

Eric Moore, M.D., elected to Mayo Clinic Board of Trustees

NYU named “research powerhouse” in new analysis

New polymer materials may offer breakthrough solution for hard-to-remove PFAS in water

Biochar can either curb or boost greenhouse gas emissions depending on soil conditions, new study finds

Nanobiochar emerges as a next generation solution for cleaner water, healthier soils, and resilient ecosystems

Study finds more parents saying ‘No’ to vitamin K, putting babies’ brains at risk

Scientists develop new gut health measure that tracks disease

Rice gene discovery could cut fertiliser use while protecting yields

Jumping ‘DNA parasites’ linked to early stages of tumour formation

Ultra-sensitive CAR T cells provide potential strategy to treat solid tumors

Early Neanderthal-Human interbreeding was strongly sex biased

North American bird declines are widespread and accelerating in agricultural hotspots

Researchers recommend strategies for improved genetic privacy legislation

How birds achieve sweet success

More sensitive cell therapy may be a HIT against solid cancers

Scientists map how aging reshapes cells across the entire mammalian body

Hotspots of accelerated bird decline linked to agricultural activity

How ancient attraction shaped the human genome

[Press-News.org] In recognizing speech sounds, the brain does not work the way a computer doesAcceptable combinations determined by reference to known words, not application of abstract rules