(Press-News.org) Johns Hopkins researchers say they have successfully used stem cells derived from human body fat to deliver biological treatments directly to the brains of mice with the most common and aggressive form of brain tumor, significantly extending their lives.

The experiments advance the possibility, the researchers say, that the technique could work in people after surgical removal of brain cancers called glioblastomas to find and destroy any remaining cancer cells in difficult-to-reach areas of the brain. Glioblastoma cells are particularly nimble; they are able to migrate across the entire brain, hide out and establish new tumors. Cure rates for the tumor are notoriously low as a result.

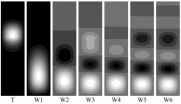

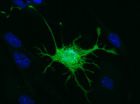

In the mouse experiments, the Johns Hopkins investigators used mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) — which have an unexplained ability to seek out cancer and other damaged cells — that they harvested from human fat tissue. They modified the MSCs to secrete bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4), a small protein involved in regulating embryonic development and known to have some tumor suppression function. The researchers, who had already given a group of mice glioblastoma cells several weeks earlier, injected stem cells armed with BMP4 into their brains.

In a report published in the May 1 issue of Clinical Cancer Research, the investigators say the mice treated this way had less tumor growth and spread, and their cancers were overall less aggressive and had fewer migratory cancer cells compared to mice that didn't get the treatment. Meanwhile, the mice that received stem cells with BMP4 survived significantly longer, living an average of 76 days, as compared to 52 days in the untreated mice.

"These modified mesenchymal stem cells are like a Trojan horse, in that they successfully make it to the tumor without being detected and then release their therapeutic contents to attack the cancer cells," says study leader Alfredo Quinones-Hinojosa, M.D., a professor of neurosurgery, oncology and neuroscience at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Standard treatments for glioblastoma include chemotherapy, radiation and surgery, but even a combination of all three rarely leads to more than 18 months of survival after diagnosis. Finding a way to get biologic therapy to mop up what other treatments can't get is a long-sought goal, says Quinones-Hinojosa, who cautions that years of additional studies are needed before human trials of fat-derived MSC therapies could begin.

Quinones-Hinojosa, who treats brain cancer patients at Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center, says his team was heartened by the fact that the stem cells let loose into the brain in his experiments did not transform themselves into new tumors.

The latest findings build on research published in March 2013 by Quinones-Hinojosa and his team in the journal PLOS ONE, which showed that harvesting MSCs from fat was much less invasive and less expensive than getting them from bone marrow, a more commonly studied method.

Ideally, he says, if MSCs work, a patient with a glioblastoma would have some adipose tissue (fat) removed from any number of locations in the body a short time before surgery. The MSCs in the fat would be drawn out and manipulated in the lab to secrete BMP4. Then, after surgeons removed the brain tumor, they could deposit these treatment-armed cells into the brain in the hopes that they would seek out and destroy the cancer cells.

INFORMATION:

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health's National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (RO1NS070024) and the Maryland Stem Cell Research Fund.

Other Johns Hopkins researchers involved in the study include Qian Li, Ph.D.; Olindi Wijesekera; Joanna Y. Wang; Mingxin Zhu, M.D.; Colette ap Rhys, Ph.D.; Kaisorn L. Chaichana, M.D.; David A. Chesler, M.D., Ph.D.; Hao Zhang, M.D.; Christopher L. Smith, Ph.D.; and Hugo Guerrero-Cazares, M.D., Ph.D. Researchers from Yale University also contributed to this work.

For more information:

http://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/news/media/releases/using_fat_to_fight_brain_cancer

Johns Hopkins Medicine (JHM), headquartered in Baltimore, Maryland, is a $6.7 billion integrated global health enterprise and one of the leading health care systems in the United States. JHM unites physicians and scientists of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine with the organizations, health professionals and facilities of The Johns Hopkins Hospital and Health System. JHM's vision, "Together, we will deliver the promise of medicine," is supported by its mission to improve the health of the community and the world by setting the standard of excellence in medical education, research and clinical care. Diverse and inclusive, JHM educates medical students, scientists, health care professionals and the public; conducts biomedical research; and provides patient-centered medicine to prevent, diagnose and treat human illness. JHM operates six academic and community hospitals, four suburban health care and surgery centers, and more than 30 primary health care outpatient sites. The Johns Hopkins Hospital, opened in 1889, was ranked number one in the nation for 21 years in a row by U.S. News & World Report.

Human fat: A trojan horse to fight brain cancer?

Johns Hopkins researchers use stem cells derived from human body fat to deliver treatment for deadly glioblastoma in mice

2014-05-01

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Crocodile tears please thirsty butterflies and bees

2014-05-01

The butterfly (Dryas iulia) and the bee (Centris sp.) were most likely seeking scarce minerals and an extra boost of protein. On a beautiful December day in 2013, they found the precious nutrients in the tears of a spectacled caiman (Caiman crocodilus), relaxing on the banks of the Río Puerto Viejo in northeastern Costa Rica.

A boat carrying students, photographers, and aquatic ecologist Carlos de la Rosa was passing slowing and quietly by, and caught the moment on film. They watched [and photographed] in barely suppressed excitement for a quarter of an hour while the ...

Competition of the multiple Gortler modes in hypersonic boundary layer flows

2014-05-01

The present study illustrates, for the hypersonic flows, through the local and marching analysis, the crossover of the mode W and the mode T at O(1) wavenumber and large Görtler number regime. In fact, it is at this wavenumber regime that the instability is most likely to occur. The two approaches are expected to deliver similar results and the marching analysis helps to express the details of the crossover and confirm the result of the local analysis.

In fact the study of Görtler instability goes back to the date of the 1940s. Since Görtler's pioneering investigation ...

Vitamin D deficiency linked to aggressive prostate cancer

2014-05-01

CHICAGO --- African-American and European-American men at high risk of prostate cancer have greater odds of being diagnosed with an aggressive form of the disease if they have a vitamin D deficiency, according to a new study from Northwestern Medicine® and the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC).

Results of the study will be published May 1 in Clinical Cancer Research, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research.

"Vitamin D deficiency could be a biomarker of advanced prostate tumor progression in large segments of the general population," said Adam ...

Extreme sleep durations may affect brain health in later life

2014-05-01

BOSTON, MA – A new research study led by Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH) published in The Journal of the American Geriatrics Society in May, shows an association between midlife and later life sleeping habits with memory; and links extreme sleep durations to worse memory in later life. The study suggests that extreme changes in sleep duration from middle age to older age may also worsen memory function.

"Sleep Duration In Midlife and Later Life In Relation to Cognition: The Nurses' Health Study," led by Elizabeth Devore, ScD, instructor in medicine in the Channing ...

New UT Arlington research could improve pharmaceuticals testing

2014-05-01

A UT Arlington chemistry professor, renowned for his work in the area of chemical separations, is leading an effort to find a more accurate way to measure water content in pharmaceuticals – a major quality issue for drug manufacturers.

Daniel W. Armstrong, UT Arlington's Robert A. Welch Chair in Chemistry, says the new technique could be 100 times more sensitive than one of the most popular current methods.

"The analysis for water in many consumer products, including drugs, is one of the most required tests done in the world," said Armstrong. "Current methods have many ...

Playing pool with carbon atoms

2014-04-30

A University of Arizona-led team of physicists has discovered how to change the crystal structure of graphene, more commonly known as pencil lead, with an electric field, an important step toward the possible use of graphene in microprocessors that would be smaller and faster than current, silicon-based technology.

Graphene consists of extremely thin sheets of graphite: when writing with a pencil, graphene sheets slough off the pencil's graphite core and stick to the page. If placed under a high-powered electron microscope, graphene reveals its sheet-like structure ...

Ground breaking technique offers DNA 'Sat Nav' direct to your ancestor's home 1,000 years ago

2014-04-30

Tracing where your DNA was formed over 1,000 years ago is now possible due to a revolutionary technique developed by a team of international scientists led by experts from the University of Sheffield.

The ground breaking Geographic Population Structure (GPS) tool, created by Dr Eran Elhaik from the University of Sheffield's Department of Animal and Plant Sciences and Dr Tatiana Tatarinova from the University of Southern California, works similarly to a satellite navigation system as it helps you to find your way home, but not the one you currently live in – but rather ...

Cutting cancer to pieces: New research on bleomycin

2014-04-30

A variety of cancers are treated with the anti-tumor agent bleomycin, though its disease-fighting properties remain poorly understood.

In a new study, lead author Basab Roy—a researcher at Arizona State University's Biodesign Institute—describes bleomycin's ability to cut through double-stranded DNA in cancerous cells, like a pair of scissors. Such DNA cleavage often leads to cell death in particular types of cancer cells.

The paper is co-authored by professor Sidney Hecht, director of Biodesign's Center for BioEnergetics. The study presents, for the first time, alternative ...

Infertile women want more support

2014-04-30

VIDEO:

University of Iowa Communication Studies researchers Keli Steuber and Andrew High talk about infertility.

Click here for more information.

Many women coping with infertility count on relatives or close friends for encouragement and assistance. But according to research at the University of Iowa, when it comes to support, women may not be receiving enough—or even the right kind.

"Infertility is a more prevalent issue than people realize. It affects one in six couples, ...

Stem cells from teeth can make brain-like cells

2014-04-30

University of Adelaide researchers have discovered that stem cells taken from teeth can grow to resemble brain cells, suggesting they could one day be used in the brain as a therapy for stroke.

In the University's Centre for Stem Cell Research, laboratory studies have shown that stem cells from teeth can develop and form complex networks of brain-like cells. Although these cells haven't developed into fully fledged neurons, researchers believe it's just a matter of time and the right conditions for it to happen.

"Stem cells from teeth have great potential to grow into ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Study reveals ancient needles and awls served many purposes

Key protein SYFO2 enables 'self-fertilization’ of leguminous plants

AI tool streamlines drug synthesis

Turning orchard waste into climate solutions: A simple method boosts biochar carbon storage

New ACP papers say health care must be more accessible and inclusive for patients and physicians with disabilities

Moisture powered materials could make cleaning CO₂ from air more efficient

Scientists identify the gatekeeper of retinal progenitor cell identity

American Indian and Alaska native peoples experience higher rates of fatal police violence in and around reservations

Research alert: Long-read genome sequencing uncovers new autism gene variants

Genetic mapping of Baltic Sea herring important for sustainable fishing

In the ocean’s marine ‘snow,’ a scientist seeks clues to future climate

Understanding how “marine snow” acts as a carbon sink

In search of the room temperature superconductor: international team formulates research agenda

Index provides flu risk for each state

Altered brain networks in newborns with congenital heart disease

Can people distinguish between AI-generated and human speech?

New robotic microfluidic platform brings ai to lipid nanoparticle design

COSMOS trial results show daily multivitamin use may slow biological aging

Immune cells play key role in regulating eye pressure linked to glaucoma

National policy to remedy harms of race-based kidney function estimation associated with increased transplants for Black patients

Study finds teens spend nearly one-third of the school day on smartphones, with frequent checking linked to poorer attention

Team simulates a living cell that grows and divides

Study illuminates the experiences of people needing to seek abortion care out of state

Digital media use and child health and development

Seeking abortion care across state lines after the Dobbs decision

Smartphone use during school hours and association with cognitive control in youths ages 11 to 18

Maternal acetaminophen use and child neurodevelopment

Digital microsteps as scalable adjuncts for adults using GLP-1 receptor agonists

Researchers develop a biomimetic platform to enhance CAR T cell therapy against leukemia

Heart and metabolic risk factors more strongly linked to liver fibrosis in women than men, study finds

[Press-News.org] Human fat: A trojan horse to fight brain cancer?Johns Hopkins researchers use stem cells derived from human body fat to deliver treatment for deadly glioblastoma in mice