(Press-News.org) LA JOLLA—Scientists at the Salk Institute have discovered the developmental source for a key type of neuron that allows animals to walk, a finding that could help pave the way for new therapies for spinal cord injuries or other motor impairments related to disease.

The spinal cord contains a network of neurons that are able to operate largely in an autonomous manner, thus allowing animals to carry out simple rhythmic walking movements with minimal attention—giving us the ability, for example, to walk while talking on the phone. These circuits control properties such as stepping with each foot or pacing the tempo of walking or running.

The researchers, led by Salk professor Martyn Goulding, identified for the first time which neurons in the spinal cord were responsible for controlling a key output of this locomotion circuit, namely the ability to synchronously activate and deactivate opposing muscles to create a smooth bending motion (dubbed flexor-extensor alternation). The findings were published April 2 in Neuron.

Motor circuits in the spinal cord are assembled from six major types of interneurons—cells that interface between nerves descending from the brain and nerves that activate or inhibit muscles. Goulding and his team had previously implicated one class of interneuron, the V1 interneurons, as being a likely key component of the flexor-extensor circuitry. However when V1 interneurons were removed, the team saw that flexor-extensor activity was still intact, leading them to suspect another type of cell was also involved in coordinating this aspect of movement.

To determine what other interneurons were at play in the flexor-extensor circuit, the team looked for other cells in the spinal cord with properties that were similar to those of the V1 neurons. In doing this they began to focus on another class of neuron, whose function was not known, V2b interneurons. Using a specialized experimental setup that allows one to monitor locomotion in the spinal cord itself, the team saw a synchronous pattern of flexor and extensor activity when V2b interneurons were inactivated along with the V1 interneurons.

The team also showed that this synchronicity led to newborn mice displaying a tetanus-like reaction when the two types of interneurons were inactivated: the limbs froze in one position because they no longer had the push-pull balance of excitation and inhibition that is needed to move.

These findings further confirm the hypothesis put forward over 120 years ago by the Nobel Prize-winning neuroscientist, Charles Sherrington, that flexor-extensor alternation is essential for locomotion in all animals that have limbs. He proposed that specialized cells in the spinal cord called switching cells performed this function. After 120 years, Goulding and researchers have now uncovered the identity of these switching cells.

"Our whole motor system is built around flexor-extension; this is the cornerstone component of movement," says Goulding, holder of Salk's Frederick W. and Joanna J. Mitchell Chair. "If you really want to understand how animals move you need to understand the contribution of these switching cells."

With a more thorough understanding of the basic science around how this flexor-extensor circuit works, scientists will be in a better position to, for example, create a system that can reactivate the spinal cord or mimic signals sent from the brain to the spinal cord.

INFORMATION:

About the Salk Institute for Biological Studies:

The Salk Institute for Biological Studies is one of the world's preeminent basic research institutions, where internationally renowned faculty probe fundamental life science questions in a unique, collaborative, and creative environment. Focused both on discovery and on mentoring future generations of researchers, Salk scientists make groundbreaking contributions to our understanding of cancer, aging, Alzheimer's, diabetes and infectious diseases by studying neuroscience, genetics, cell and plant biology, and related disciplines.

Faculty achievements have been recognized with numerous honors, including Nobel Prizes and memberships in the National Academy of Sciences. Founded in 1960 by polio vaccine pioneer Jonas Salk, M.D., the Institute is an independent nonprofit organization and architectural landmark.

Salk scientists reveal circuitry of fundamental motor circuit

2014-05-02

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Which came first, bi- or tricellular pollen? New research updates a classic debate

2014-05-02

With the bursting of spring, pollen is in the air. Most of the pollen that is likely tickling your nose and making your eyes water is being dispersed in a sexually immature state consisting of only two cells (a body cell and a reproductive cell) and is not yet fertile. While the majority of angiosperm species disperse their pollen in this early, bicellular, stage of sexual maturity, about 30% of flowering plants disperse their pollen in a more mature fertile stage, consisting of three cells (a body and two sperm cells). And then there are plants that do both.

So which ...

Researchers find unique fore wing folding among Sub-Saharan African Ensign wasps

2014-05-02

Researchers discovered several possibly threatened new species of ensign wasps from Sub-Saharan Africa -- the first known insects to exhibit transverse folding of the fore wing. The scientists made this discovery, in part, using a technique they developed that provides broadly accessible anatomy descriptions.

"Ensign wasps are predators of cockroach eggs, and the transverse folding exhibited by these species may enable them to protect their wings while developing inside the cramped environment of cockroach egg cases," said Andy Deans, associate professor of entomology, ...

Probing dopant distribution

2014-05-02

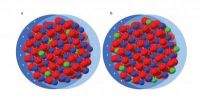

The icing on the cake for semiconductor nanocrystals that provide a non-damped optoelectronic effect may exist as a layer of tin that segregates near the surface.

One method of altering the electrical properties of a semiconductor is by introducing impurities called dopants. A team led by Delia Milliron, a chemist at Berkeley Lab's Molecular Foundry, a U.S Department of Energy (DOE) national nanoscience center, has demonstrated that equally important as the amount of dopant is how the dopant is distributed on the surface and throughout the material. This opens the door ...

Drinking poses greater risk for advanced liver disease in HIV/hep C patients

2014-05-02

PHILADELPHIA—Consumption of alcohol has long been associated with an increased risk of advanced liver fibrosis, but a new study published online in Clinical Infectious Diseases from researchers at Penn Medicine and other institutions shows that association is drastically heightened in people co-infected with both HIV and chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Even light ("nonhazardous") drinking—which typically poses a relatively low risk for uninfected persons—was linked to an increased risk of liver fibrosis in the co-infected group.

Reasons for this are not fully ...

Space Station research shows that hardy little space travelers could colonize Mars

2014-05-02

In the movies, humans often fear invaders from Mars. These days, scientists are more concerned about invaders to Mars, in the form of micro-organisms from Earth. Three recent scientific papers examined the risks of interplanetary exchange of organisms using research from the International Space Station. All three, Survival of Rock-Colonizing Organisms After 1.5 Years in Outer Space, Resistance of Bacterial Endospores to Outer Space for Planetary Protection Purposes and Survival of Bacillus pumilus Spores for a Prolonged Period of Time in Real Space Conditions, have appeared ...

Story tips from the Department of Energy's Oak Ridge National Laboratory, May 2014

2014-05-02

To arrange for an interview with a researcher, please contact the Communications staff member identified at the end of each tip. For more information on ORNL and its research and development activities, please refer to one of our media contacts. If you have a general media-related question or comment, you can send it to news@ornl.gov.

DIESELS – Reducing soot . . .

Nine U.S. diesel engine manufacturers and Oak Ridge National Laboratory are using their collective horsepower to tackle the perennial industry-wide problem of efficiency-robbing soot in engines. Over time, ...

Vanderbilt study explores genetics behind Alzheimer's resiliency

2014-05-02

Autopsies have revealed that some individuals develop the cellular changes indicative of Alzheimer's disease without ever showing clinical symptoms in their lifetime.

Vanderbilt University Medical Center memory researchers have discovered a potential genetic variant in these asymptomatic individuals that may make brains more resilient against Alzheimer's.

"Most Alzheimer's research is searching for genes that predict the disease, but we're taking a different approach. We're looking for genes that predict who among those with Alzheimer's pathology will actually show ...

Researchers find way to decrease chemoresistance in ovarian cancer

2014-05-02

ATLANTA--Inhibiting enzymes that cause changes in gene expression could decrease chemotherapy resistance in ovarian cancer patients, researchers at Georgia State University and the University of Georgia say.

Dr. Susanna Greer, associate professor of biology, and research partners at the University of Georgia have identified two enzymes that suppress proteins that are important for regulating cell survival and chemoresistance in ovarian cancer. Their findings are published in the journal, PLOS ONE.

Ovarian cancer is one of the deadliest gynecological cancers, with a ...

A transcription factor called SLUG helps determines type of breast cancer

2014-05-02

Findings and Significance: During breast-tissue development, a transcription factor called SLUG plays a role in regulating stem cell function and determines whether breast cells will mature into luminal or basal cells.

Studying factors, such as SLUG, that regulate stem-cell activity and breast-cell identity are important for understanding how breast tumors arise and develop into different subtypes. Ultimately, this knowledge may help the development of novel therapies targeted to specific breast-tumor subtypes.

Background: Stem cells are immature cells that can differentiate, ...

Key protein, FABP5, enhances memory and learning

2014-05-02

Case Western Reserve researchers have discovered that a protein previously implicated in disease plays such a positive role in learning and memory that it may someday contribute to cures of cognitive impairments. The findings regarding the potential virtues of fatty acid binding protein 5 (FABP5) — usually associated with cancer and psoriasis — appear in the May 2 edition of The Journal of Biological Chemistry.

"Overall, our data show that FABP5 enhances cognitive function and that FABP5 deficiency impairs learning and memory functions in the brain hippocampus region," ...