(Press-News.org) SALT LAKE CITY, May 5, 2014 – When University of Utah biologists set out cotton balls treated with a mild pesticide, wild finches in the Galapagos Islands used the cotton to help build their nests, killing parasitic fly maggots to protect baby birds. The researchers say the self-fumigation method may help endangered birds and even some mammals.

"We are trying to help birds help themselves," says biology professor Dale Clayton, senior author of a study outlining the new technique. The findings were published online May 5, 2014, in the journal Current Biology.

"Self-fumigation is important because there currently are no other methods to control this parasite," blood-sucking maggots of the nest fly Philornis downsi, says University of Utah biology doctoral student Sarah Knutie, the study's first author.

Clayton says the parasitic nest fly may have invaded Ecuador's Galapagos Islands via ships and boats from the mainland at an unknown time and "showed up in large numbers in the 1990s. So the birds have no history with these flies, which is why they are sitting ducks. From the perspective of the birds, these things are from Mars."

Knutie says the flies now infest all land birds there, including most of the 14 species of Darwin's finches, two of which are endangered: fewer than 100 mangrove finches remain on Isabela Island, and only about 1,620 medium tree finches exist, all on Floreana Island. Nest flies have been implicated in population declines of Darwin's finches, including the two endangered species.

Clayton says the pesticide – permethrin – is safe for the birds: "It might kill a few other insects in the nest. This is the same stuff in head-lice shampoo you put on your kid. Permethrin is safe. No toxicologist is going to argue with that. The more interesting question is whether the flies will evolve resistance, as human head lice have done."

Clayton believes that will not happen if treated cotton is placed only in the habitats of endangered finches, not others.

Knutie and Clayton conducted the study with University of Utah doctoral students Sabrina McNew and Andrew Bartlow, and with Daniela Vargas, now of the Autonomous University of Barcelona in Spain. The study was funded by the National Science Foundation, the University of Utah and a crowd-funding campaign.

Can Other Species Fumigate Themselves?

Knutie and Clayton say their method might help the endangered mangrove finches, with only 60 cotton dispensers needed to cover the less than half a square mile inhabited by the birds on Isabela Island. So scientists there recently started a preliminary experiment to determine if mangrove finches will collect cotton balls from dispensers.

"There are other species of birds that are hurt by parasites, and so if the birds can be encouraged to incorporate fumigated cotton into their nests, then they may be able to lessen the effects of the parasites," Knutie says.

Examples: Hawaiian honeycreepers infested with feather lice, birds in Puerto Rico afflicted by Philornis flies and the endangered Florida scrub jay parasitized by fleas.

The same method might be used for the black-tailed prairie dog – removed from the endangered species list but still declining on the Great Plains and often infected by fleas with plague bacteria, Knutie says. Permethrin has been sprayed in burrows, but that is labor-intensive, so it might be used on vegetation the animals drag into their burrows.

Knutie says permethrin-treated cotton has been used in the Northeast to get mice to incorporate it in their nests to kill Lyme disease-carrying ticks. Results weren't clear.

Finches Nipping at a Clothesline

The new study was done in the Galapagos Islands, where the diversity of finches helped inspire Charles Darwin's theory of evolution after he visited in the 1830s.

Knutie got the idea for the new study four years ago at her dorm in the Galapagos when she noticed Darwin's finches "were coming to my laundry line, grabbing frayed fibers from the line and taking it away, presumably back to their nests," she recalls. The birds also collect toilet paper, string and fibers from towels.

Parasitic nest flies lay their eggs in finch nests, which have dome-shaped roofs of woven plant fibers. When the eggs hatch, they become larva or maggots, which feed on the blood of nestlings and on mother finches brooding their eggs and nestlings.

Past studies found that in some years, maggots kill all the nestlings in nests they parasitize, but spraying nests with 1 percent permethrin solution eradicates the maggots.

So Knutie wondered if finches could be encouraged to pick up treated cotton to fumigate their own nests, located in tree cacti and acacia trees. She ran her study during January-April 2013 at a site named El Garrapatero on the Galapagos' Santa Cruz Island.

The biologists built wire-mesh dispensers for the cotton. They tried processed cotton balls treated with 1 percent permethrin solution and, as a control, unprocessed cotton balls treated with water. Processed and unprocessed cotton balls appear slightly different, so researchers could distinguish treated or untreated cotton in nests.

In a preliminary experiment, Knutie showed the birds had no preference for collecting treated versus untreated cotton, or for processed or unprocessed cotton. In another preliminary test, the researchers showed that the finches, which are territorial, travel no more than 55 feet from their nests to collect nest-building material.

Collecting Cotton Balls and Killing Maggots

During the key experiment, Knutie and colleagues set up two lines of 15 cotton dispensers – one line on each side of a road in arid scrub woodland. In each line, dispensers alternated between treated and untreated cotton, and dispensers were 130 feet apart – more than twice 55 feet, making it likely each nesting finch had a favorite dispenser. That was confirmed: none of the nests were found to have both types of cotton.

The researchers searched for active finch nests weekly within 65 feet of each dispenser, using a camera on a pole to check each nest and confirm breeding activity.

They found cotton balls were collected by at least four species of Darwin's finches: the medium ground finch (Geospiza fortis), small ground finch (Geospiza fuliginosa), small tree finch (Camarhynchus parvulus) and vegetarian finch (Platyspiza crassirostris). In some cases, researchers were unsure which species occupied a nest.

After birds in a given nest finished breeding (within three weeks) and left the nest, the scientists collected the nest, dissected it, counted the number of parasitic fly maggots and then weighed and separated all the nest materials, including cotton.

The Utah biologists found 26 active nests, of which 22 (85 percent) contained cotton: 13 nests had permethrin-treated cotton, nine had untreated cotton and four had no cotton. Regardless of treatment, the amount of cotton in nests and the percent of the nest made of cotton didn't vary significantly.

The researchers write that their study found "self-fumigation had a significant negative effect on parasites," killing at least half the fly maggots. The 13 nests with treated cotton averaged 15 maggots, give or take 10. Nests with untreated cotton averaged 30 maggots, give or take eight.

The amount of untreated cotton in a nest was unrelated to the number of maggots; but the more treated cotton, the fewer the parasites. Of eight nests with at least 1 gram of cotton (one 28th of an ounce), seven had no maggots and one nest had four.

"If the birds insert a gram or more of treated cotton – about a thimbleful – it kills 100 percent of the fly larvae," Clayton says.

A separate follow-up experiment – and earlier studies by others – showed killing the parasites with sprayed permethrin increases baby bird survival. The researchers did not study survival of offspring in nests with cotton balls because that requires repeatedly climbing to nests so birds can be weighed and banded, which might disrupt the birds from self-fumigating their nests with cotton balls.

INFORMATION:

University of Utah Communications

75 Fort Douglas BoulevardSalt Lake City, UT 84113

801-581-6773fax: 801-585-3350

http://www.unews.utah.edu

Is self-fumigation for the birds?

Save threatened species by giving them treated cotton for nests

2014-05-05

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

With 'self-fumigation,' Darwin's finches combat deadly parasitic flies

2014-05-05

Researchers have found a way to protect threatened Darwin's finches on the Galápagos Islands from deadly parasitic nest flies in a manner that's as simple as it is ingenious: by offering the birds insecticide-treated cotton for incorporation into their nests. The study, reported in the Cell Press journal Current Biology on May 5, shows that the birds will readily weave the protective fibers in. What's more, the researchers find that just one gram of treated cotton is enough to keep a nest essentially parasite-free.

The findings come as welcome news for the future of Darwin's ...

Tracking turtles through time, Dartmouth-led study may resolve evolutionary debate

2014-05-05

Turtles are more closely related to birds and crocodilians than to lizards and snakes, according to a study from Dartmouth, Yale and other institutions that examines one of the most contentious questions in evolutionary biology.

The findings appear in the journal Evolution & Development. A PDF of the study is available on request.

The research team looked at how the major groups of living reptiles, which number more than 20,000 species, are interrelated. The relationships of some reptile groups are well understood -- birds are most closely related to crocodilians among ...

Climate change threatens to worsen US ozone pollution

2014-05-05

BOULDER -- Ozone pollution across the continental United States will become far more difficult to keep in check as temperatures rise, according to new research led by the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR). The detailed study shows that Americans face the risk of a 70 percent increase in unhealthy summertime ozone levels by 2050.

This is because warmer temperatures and other changes in the atmosphere related to a changing climate, including higher atmospheric levels of methane, spur chemical reactions that lead to ozone.

Unless emissions of specific pollutants ...

Genetic, environmental influences equally important risk for autism spectrum disorder

2014-05-05

In the largest family study on autism spectrum disorder (ASD) to date, researchers from the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, along with a research team from the Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm Sweden and King's College in London found that individual risk of ASD and autistic disorder increased with greater genetic relatedness in families – that is, persons with a sibling, half-sibling or cousin diagnosed with autism have an increased likelihood of developing ASD themselves. Furthermore, the research findings showed that "environmental" factors unique to the ...

Energy-subsidy reform can be achieved with proper preparation, outside pressure

2014-05-05

HOUSTON – (May 5, 2014) – Reform of energy subsidies in oil-exporting countries can reduce carbon emissions and add years to oil exports, according to a new paper from Rice University's Baker Institute for Public Policy.

"Navigating the Perils of Energy-Subsidy Reform in Exporting Countries" was authored by Jim Krane, the Wallace S. Wilson Fellow for Energy Studies at the Baker Institute, who specializes in energy geopolitics. The paper reviews the record of energy-subsidy reforms and argues that big exporters should reduce energy demand by raising prices, and that this ...

Liver cancer screening highly beneficial for people with cirrhosis

2014-05-05

DALLAS – May 5, 2014 – Liver cancer survival rates could be improved if more people with cirrhosis are screened for tumors using inexpensive ultrasound scans and blood tests, according to a review by doctors at UT Southwestern Medical Center.

The meta-analysis of 47 studies involving more than 15,000 patients found that the three-year survival rate was much higher among patients who received liver cancer screening— 51 percent for patients who were screened compared to 28 percent of unscreened patients. The review also found that cirrhosis patients who were screened for ...

Study finds family-based exposure therapy effective treatment for young children with OCD

2014-05-05

PROVIDENCE, R.I. – A new study from the Bradley Hasbro Children's Research Center has found that family-based cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is beneficial to young children between the ages of five and eight with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD). The study, now published online in JAMA Psychiatry, found developmentally sensitive family-based CBT that included exposure/response prevention (EX/RP) was more effective in reducing OCD symptoms and functional impairment in this age group than a similarly structured relaxation program.

Jennifer Freeman, Ph.D., a staff ...

Tomato turf wars: Benign bug bests salmonella; tomato eaters win

2014-05-05

Scientists from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have identified a benign bacterium that shows promise in blocking Salmonella from colonizing raw tomatoes. Their research is published ahead of print in the journal Applied and Environmental Microbiology.

When applied to Salmonella-contaminated tomato plants in a field study, the bacterium, known as Paenibacillus alvei, significantly reduced the concentration of the pathogen compared to controls.

Outbreaks of Salmonella traced to raw tomatoes have sickened nearly 2,000 people in the US from 2000-2010, killing ...

Physician practice facilitation ensures key medical care reaches children

2014-05-05

Leona Cuttler, MD, knew in her core that the simple act of adding an outside eye could dramatically improve pediatric care.

Today, a study of more than 16,000 patient visits published online in the journal Pediatrics proves Cuttler's thesis correct. The lead investigator on the research project, Cuttler succumbed to cancer late last year. But her colleagues are committed to seeing its lessons disseminated across the country.

"It was an honor to work on this project with Dr. Cuttler," said study first author Sharon B. Meropol, MD, PhD, Assistant Professor, Departments ...

ORNL paper examines clues for superconductivity in an iron-based material

2014-05-05

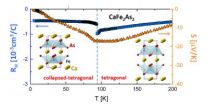

OAK RIDGE, Tenn., May 5, 2014 – For the first time, scientists have a clearer understanding of how to control the appearance of a superconducting phase in a material, adding crucial fundamental knowledge and perhaps setting the stage for advances in the field of superconductivity.

The paper, published in Physical Review Letters, focuses on a calcium-iron-arsenide single crystal, which has structural, thermodynamic and transport properties that can be varied through carefully controlled synthesis, similar to the application of pressure. To make this discovery, researchers ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Kidney cancer study finds belzutifan plus pembrolizumab post-surgery helps patients at high risk for relapse stay cancer-free longer

Alkali cation effects in electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction

Test platforms for charging wireless cars now fit on a bench

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

Yes! The role of YAP and CTGF as potential therapeutic targets for preventing severe liver disease

Pancreatic cancer may begin hiding from the immune system earlier than we thought

[Press-News.org] Is self-fumigation for the birds?Save threatened species by giving them treated cotton for nests