(Press-News.org) WASHINGTON D.C. May 6, 2013 -- A team of U.K. researchers has developed a way to dramatically reduce the complexity of modeling "bistable" systems which involve the interaction of two evolving species where one changes faster than the other ("slow-fast systems"). Described in The Journal of Chemical Physics, the work paves the way for easier computational simulations and predictions involving such systems, which are found in fields as diverse as chemistry, biology and ecology.

Imagine, for instance, trying to predict how a population of whales would fare based on the impact of fluctuating ocean levels of plankton, if that was their primary food source. It might seem easy enough to estimate how many happy whales you will have given a relatively constant supply of plankton, but it's much harder to reckon what will happen to the population when their food source fluctuates dramatically.

That's much closer to reality: over their lifetimes, your average whale could endure multiple feasts and famines according to plankton's fickle blooms, and accurately predicting the impacts these will have on the whale population are made possible only by accounting for both the slow whale population dynamics and the much faster and widely fluctuating plankton population dynamics. This situation can be represented as a classic "bistable" problem: conceptually challenging, mathematically complicated, computationally intensive and, until now, nearly impossible to solve.

But hitting upon a solution that was in itself somewhat bistable, Maria Bruna and colleagues at the University of Oxford's Mathematical Institute and at Microsoft Research's Computational Science Laboratory in Cambridge, England developed a new method for deriving simpler models of bistable systems.

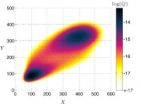

Their solution involved combining two existing mathematical techniques called "slow manifold theory," which is applied to slow-fast systems; and "perturbation theory," which is used for the study of metastable transitions. They tested this approach against the more standard, computationally expensive model that exhaustively treated the fast processes to predict the slow. What their results showed was that their simpler method worked just as well at predicting the slow process. Then they applied this to a predator-prey model and showed that it could accurately calculate the time to extinction of the predator (the slow species, like the whale) when the abundance of its prey (the fast species, like the plankton) fluctuates around two alternative states.

A key advantage of the new approach is that it allowed the researchers to obtain the accurate time-dependent behavior of the slow variable, in contrast to earlier methods that are only useful to compute equilibrium quantities.

"Using this method one can obtain accurate simulations of the process of interest that take into account the effect of the fast bistable processes, but much more cheaply," Bruna said.

"Since the reduction method is systematic, it can be easily applied to other systems and extended to higher dimensions," she added. For instance, the method could be extended to help understand why some ecosystems, consisting of multiple fast-slow interaction processes, fail to return to their original state after being perturbed by harvesting.

INFORMATION:

The article, "Model reduction for slow-fast stochastic systems with metastable behaviour," is authored by Maria Bruna, S. Jonathan Chapman and Matthew J. Smith. It will be published in The Journal of Chemical Physics on Tuesday May 6, 2014 (DOI: 10.1063/1.4873343). After that date it will be available at: http://scitation.aip.org/content/aip/journal/jcp/140/17/10.1063/1.4873343

ABOUT THE JOURNAL

The Journal of Chemical Physics publishes concise and definitive reports of significant research in the methods and applications of chemical physics. See: http://jcp.aip.org

Predator-prey made simple

New method described in 'The Journal of Chemical Physics' simplifies studies of predator-prey interactions and other 'bistable' systems

2014-05-06

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

A cup of coffee a day may keep retinal damage away

2014-05-06

ITHACA, N.Y. – Coffee drinkers, rejoice! Aside from java's energy jolt, food scientists say you may reap another health benefit from a daily cup of joe: prevention of deteriorating eyesight and possible blindness from retinal degeneration due to glaucoma, aging and diabetes.

Raw coffee is, on average, just 1 percent caffeine, but it contains 7 to 9 percent chlorogenic acid, a strong antioxidant that prevents retinal degeneration in mice, according to a Cornell study published in the Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry.

The retina is a thin tissue layer on the ...

Expert guidance strengthens strategies to prevent most common and costly infection

2014-05-06

CHICAGO (May 6, 2014) – Surgical site infections (SSIs) are the most common and costly healthcare-associated infection (HAI) in the United States. New evidence-based recommendations provide a framework for healthcare institutions to prioritize and implement strategies to reduce the number of infections.

The guidelines are published in the June issue of Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology and were produced in a collaborative effort led by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the American Hospital Association, ...

New expert guidelines aim to focus hospitals' infectious diarrhea prevention efforts

2014-05-06

CHICAGO (May 6, 2014) – With rates of Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) now rivaling drug-resistant Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) as the most common bacteria to cause healthcare-associated infections, new expert guidance encourages healthcare institutions to implement and prioritize prevention efforts for this infectious diarrhea. The guidelines are published in the June issue of Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology.

The new practice recommendations are a part of Compendium of Strategies to Prevent Healthcare-Associated Infections in Acute ...

As kids age, snacking quality appears to decline

2014-05-06

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — The average U.S. child snacks three times a day. Concerned about the role of snacking in obesity, a team of researchers set out to explore how eating frequency relates to energy intake and diet quality in a sample of low-income, urban schoolchildren in the Boston area. They expected that snacking would substantially contribute to kids' overall energy intake, and the new data confirm that. But they were surprised that the nutritional value of snacks and meals differed by age.

The findings, led by first author E. Whitney Evans, a ...

Planck reveals magnetic fingerprint of our galaxy

2014-05-06

The team—which includes researchers from the University of British Columbia and the Canadian Institute for Theoretical Astrophysics (CITA) at the University of Toronto—created the map using data from the Planck Space Telescope. Since 2009, Planck has charted the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB), the light from the Universe a mere 380,000 years after the Big Bang.

But Planck also observes light from much closer than the farthest reaches of time and space. With an instrument called the High Frequency Instrument (HFI), Planck detects the light from microscopic dust particles ...

GW researcher discovers the mechanisms that link brain alertness and increased heart rate

2014-05-06

WASHINGTON (May 6, 2014) — George Washington University (GW) researcher David Mendelowitz, Ph.D., was recently published in the Journal of Neuroscience for his research on how heart rate increases in response to alertness in the brain. Specifically, Mendelowitz looked at the interactions between neurons that fire upon increased attention and anxiety and neurons that control heart rate to discover the "why," "how," and "where to next" behind this phenomenon.

"This study examines how changes in alertness and focus increase your heart rate," said Mendelowitz, vice chair ...

Scientists identify new protein in the neurological disorder dystonia

2014-05-06

MANHATTAN, Kan. — A collaborative discovery involving Kansas State University researchers may lead to the first universal treatment for dystonia, a neurological disorder that affects nearly half a million Americans.

Michal Zolkiewski, associate professor of biochemistry and molecular biophysics at Kansas State University, and Jeffrey Brodsky at the University at Pittsburgh co-led a study that focused on a mutated protein associated with early onset torsion dystonia, or EOTD, the most severe type of dystonia that typically affects adolescents before the age of 20. Dystonia ...

International team maps nearly 200,000 global glaciers in quest for sea rise answers

2014-05-06

An international team led by glaciologists from the University of Colorado Boulder and Trent University in Ontario, Canada has completed the first mapping of virtually all of the world's glaciers -- including their locations and sizes -- allowing for calculations of their volumes and ongoing contributions to global sea rise as the world warms.

The team mapped and catalogued some 198,000 glaciers around the world as part of the massive Randolph Glacier Inventory, or RGI, to better understand rising seas over the coming decades as anthropogenic greenhouse gases heat the ...

GW researcher looks 'inside the box' for a sustainable solution for intestinal parasites

2014-05-06

WASHINGTON (May 6, 2014) — According to the World Health Organization, more than 450 million people worldwide, primarily children and pregnant women, suffer illness from soil-transmitted helminths (STH), intestinal parasites that live in humans and other animals. Considerable effort and resources have been, and continue to be, spent on top-down, medical-based programs focused on administering drugs to control STH infections, with little success. John Hawdon, Ph.D., associate professor of microbiology, immunology, and tropical medicine at the George Washington University ...

Substantial improvements made in EPA's IRIS Program, report says

2014-05-06

WASHINGTON – A new congressionally mandated report from the National Research Council says that changes EPA has proposed and implemented into its Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS) process are "substantial improvements." While acknowledging the progress made to date, the report offers further guidance and recommendations to improve the overall scientific and technical performance of the program, which is used to assess the hazards posed by environmental contaminants.

In 2011, a Research Council committee reviewed EPA's IRIS assessment for formaldehyde and found ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Trapping light on thermal photodetectors shatters speed records

New review highlights the future of tubular solid oxide fuel cells for clean energy systems

Pig farm ammonia pollution may indirectly accelerate climate warming, new study finds

Modified biochar helps compost retain nitrogen and build richer soil organic matter

First gene regulation clinical trials for epilepsy show promising results

Life-changing drug identified for children with rare epilepsy

Husker researchers collaborate to explore fear of spiders

Mayo Clinic researchers discover hidden brain map that may improve epilepsy care

NYCST announces Round 2 Awards for space technology projects

How the Dobbs decision and abortion restrictions changed where medical students apply to residency programs

Microwave frying can help lower oil content for healthier French fries

In MS, wearable sensors may help identify people at risk of worsening disability

Study: Football associated with nearly one in five brain injuries in youth sports

Machine-learning immune-system analysis study may hold clues to personalized medicine

A promising potential therapeutic strategy for Rett syndrome

How time changes impact public sentiment in the U.S.

Analysis of charred food in pot reveals that prehistoric Europeans had surprisingly complex cuisines

As a whole, LGB+ workers in the NHS do not experience pay gaps compared to their heterosexual colleagues

How cocaine rewires the brain to drive relapse

Mosquito monitoring through sound - implications for AI species recognition

UCLA researchers engineer CAR-T cells to target hard-to-treat solid tumors

New study reveals asynchronous land–ocean responses to ancient ocean anoxia

Ctenophore research points to earlier origins of brain-like structures

Tibet ASγ experiment sheds new light on cosmic rays acceleration and propagation in Milky Way

AI-based liquid biopsy may detect liver fibrosis, cirrhosis and chronic disease signals

Hope for Rett syndrome: New research may unlock treatment pathway for rare disorder with no cure

How some skills become second nature

SFU study sheds light on clotting risks for female astronauts

UC Irvine chemists shed light on how age-related cataracts may begin

Machine learning reveals Raman signatures of liquid-like ion conduction in solid electrolytes

[Press-News.org] Predator-prey made simpleNew method described in 'The Journal of Chemical Physics' simplifies studies of predator-prey interactions and other 'bistable' systems