(Press-News.org) A scientific team led by the Gladstone Institutes and UC San Francisco has discovered that a common form of a gene already associated with long life also improves learning and memory, a finding that could have implications for treating age-related diseases like Alzheimer's.

The researchers found that people who carry a single copy of the KL-VS variant of the KLOTHO gene perform better on a wide variety of cognitive tests. When the researchers modeled the effects in mice, they found it strengthened the connections between neurons that make learning possible – what is known as synaptic plasticity – by increasing the action of a cell receptor critical to forming memories.

The discovery is a major step toward understanding how genes improve cognitive ability and could open a new route to treating diseases like Alzheimer's. Researchers have long suspected that some people may be protected from the disease because of their greater cognitive capacity, or reserve. Since elevated levels of the klotho protein appear to improve cognition throughout the lifespan, raising klotho levels could build cognitive reserve as a bulwark against the disease.

"As the world's population ages, cognitive frailty is our biggest biomedical challenge," said Dena Dubal, MD, PhD, assistant professor of neurology, the David A. Coulter Endowed Chair in Aging and Neurodegeneration at UCSF and lead author of the study, published May 8 in Cell Reports. "If we can understand how to enhance brain function, it would have a huge impact on people's lives."

Klotho was discovered in 1997 and named after the Fate from Greek mythology who spins the thread of life. The investigators found that people who carry a single copy of the KL-VS variant of the KLOTHO gene, roughly 20 percent of the population, have more klotho protein in their blood than non-carriers. Besides increasing the secretion of klotho, the KL-VS variant may also change the action of the protein and is known to lessen age-related cardiovascular disease and promote longevity.

The team's report is the first to link the KL-VS variant, or allele, to better cognition in humans, and buttresses these findings with genetic, electrophysiological, biochemical and behavioral experiments in mice. The researchers tested the associations between the allele and age-related human cognition in three separate studies involving more than 700 people without dementia between the ages of 52 and 85. Altogether, it took about three years to conduct the work.

"These surprising results pave a promising new avenue of research," said Roderick Corriveau, Ph.D., program director at NIH's National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). "Although preliminary, they suggest klotho could be used to bump up cognition for people suffering from dementia."

Having the KL-VS allele did not seem to protect people from age-related cognitive decline. But overall the effect was to boost cognition, so that the middle-aged study participants began their decline from a higher point.

"Based on what was known about klotho, we expected it to affect the brain by changing the aging process," said senior author Lennart Mucke, MD, who directs neurological research at the Gladstone Institutes and is a professor of neurology and the Joseph B. Martin Distinguished Professor of Neuroscience at UCSF. "But this is not what we found, which suggested to us that we were on to something new and different."

To get a closer look at how the gene variant operates, the researchers used mice that were engineered to produce more of the mouse version of klotho and found that these mice learned better at all stages of life. Put through mazes, these transgenic mice were more likely to try different routes, an indication that they had superior working memory. In a test of spatial learning and memory, the mice with extra klotho performed twice as well.

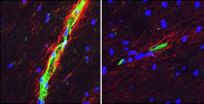

Researchers then analyzed the mouse brain tissue and found that the mice with elevated klotho had twice as many GluN2B subunits within synaptic connections. GluN2B is part of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor, or NMDAR, a key receptor involved in synaptic plasticity.

The researchers found more GluN2B-containing receptors in the hippocampus and frontal cortex, brain regions that support cognitive functions. When the researchers gave the mice a drug that blocks the action of these receptors, the klotho-enhanced mice lost their cognitive advantage.

INFORMATION:

An international team of scientists contributed to this research, including Jennifer Yokoyama, of UCSF; Lei Zhu, of UCSF and Gladstone; Lauren Broestl, of UCSF; Kurtresha Worden of Gladstone and UCSF; Dan Wang, of UCSF; Virginia Sturm, of UCSF; Daniel Kim of Gladstone; Eric Klein of UCLA; Gui-Qiu Yu, of Gladstone; Kaitlyn Ho of Gladstone; Kirsten Eilertson of Gladstone; Lei Yu, of Rush University Medical Center; Makoto Kuro-o of UT Southwestern Medical Center and Jichi Medical University; Philip De Jager, of Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School and the Broad Institute; Giovanni Coppola, of UCLA; Gary Small, of UCLA; David Bennett, of Rush; Joel Kramer, of UCSF; Carmela Abraham, of Boston University; and Bruce Miller, of UCSF.

The study was funded by the Coulter-Weeks Foundation, the SD Bechtel, Jr., Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the MetLife Foundation, the American Federation for Aging Research and the Hillblom Aging Network.

Gladstone is an independent nonprofit biomedical research organization dedicated to accelerating the pace of scientific discovery and innovation to prevent, treat and cure cardiovascular, viral and neurological diseases. It is affiliated with the University of California, San Francisco.

UCSF is a leading university dedicated to promoting health worldwide through advanced biomedical research, graduate-level education in the life sciences and health professions, and excellence in patient care. It includes top-ranked graduate schools of dentistry, medicine, nursing and pharmacy, a graduate division with nationally renowned programs in basic, biomedical, translational and population sciences, as well as a preeminent biomedical research enterprise and two top-ranked hospitals, UCSF Medical Center and UCSF Benioff Children's Hospital San Francisco.

Better cognition seen with gene variant carried by 1 in 5

2014-05-08

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Penn yeast study identifies novel longevity pathway

2014-05-08

PHILADELPHIA - Ancient philosophers looked to alchemy for clues to life everlasting. Today, researchers look to their yeast. These single-celled microbes have long served as model systems for the puzzle that is the aging process, and in this week's issue of Cell Metabolism, they fill in yet another piece.

The study, led by researchers at the University of Pennsylvania, identifies a new molecular circuit that controls longevity in yeast and more complex organisms and suggests a therapeutic intervention that could mimic the lifespan-enhancing effect of caloric restriction, ...

Study helps explain why MS is more common in women

2014-05-08

A newly identified difference between the brains of women and men with multiple sclerosis (MS) may help explain why so many more women than men get the disease, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis report.

In recent years, the diagnosis of MS has increased more rapidly among women, who get the disorder nearly four times more than men. The reasons are unclear, but the new study is the first to associate a sex difference in the brain with MS.

The findings appear May 8 in The Journal of Clinical Investigation.

Studying mice and people, ...

Immune cells found to fuel colon cancer stem cells

2014-05-08

ANN ARBOR, Mich. — A subset of immune cells directly target colon cancers, rather than the immune system, giving the cells the aggressive properties of cancer stem cells.

So finds a new study that is an international collaboration among researchers from the United States, China and Poland.

"If you want to control cancer stem cells through new therapies, then you need to understand what controls the cancer stem cells," says senior study author Weiping Zou, M.D., Ph.D., Charles B. de Nancrede Professor of surgery, immunology and biology at the University of Michigan Medical ...

What doesn't kill you may make you live longer

2014-05-08

What is the secret to aging more slowly and living longer? Not antioxidants, apparently.

Many people believe that free radicals, the sometimes-toxic molecules produced by our bodies as we process oxygen, are the culprit behind aging. Yet a number of studies in recent years have produced evidence that the opposite may be true.

Now, researchers at McGill University have taken this finding a step further by showing how free radicals promote longevity in an experimental model organism, the roundworm C. elegans. Surprisingly, the team discovered that free radicals – also ...

Population genomics study provides insights into how polar bears adapt to the Arctic

2014-05-08

May 8, 2014, Shenzhen, China – In a paper published in the May 8 issue of the journal Cell as the cover story, researches from BGI, University of California, University of Copenhagen and other institutes presented the first polar bear genome and their new findings about how polar bear successfully adapted to life in the high Arctic environment, and its demographic history throughout the history of its adaptation.

Polar bears are at the top of the food chain, and spend most of their lifetimes on the sea ice largely within the Arctic Circle. They were well known to the ...

How immune cells use steroids

2014-05-08

Hinxton, 8 May 2014 – Researchers at the European Bioinformatics Institute (EMBL-EBI) and the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute have discovered that some immune cells turn themselves off by producing a steroid. The findings, published in Cell Reports, have implications for the study of cancers, autoimmune diseases and parasitic infections.

If you've ever used a steroid, for example cortisone cream on eczema, you'll have seen first-hand how efficient steroids are at suppressing the immune response. Normally, when your body senses that immune cells have finished their job, ...

Just keep your promises: Going above and beyond does not pay off

2014-05-08

May 8, 2014 - If you are sending Mother's Day flowers to your mom this weekend, chances are you opted for guaranteed delivery: the promise that they will arrive by a certain time. Should the flowers not arrive in time, you will likely feel betrayed by the sender for breaking their promise. But if they arrive earlier, you likely will be no happier than if they arrive on time, according to new research. The new work suggests that we place such a high premium on keeping a promise that exceeding it confers little or no additional benefit.

Whether we make them with a person ...

Universal neuromuscular training an inexpensive, effective way to reduce

2014-05-08

ROSEMENT, Ill.─As participation in high-demand sports such as basketball and soccer has increased over the past decade, so has the number of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries in teens and young adults. In a study appearing today in the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (JBJS) (a research summary was presented at the 2014 Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons in March), researchers found that universal neuromuscular training for high school and college-age athletes—which focuses on the optimal way to bend, jump, land and pivot the knee—is ...

Collaboration between psychologists and physicians important to improving primary health care

2014-05-08

WASHINGTON - Primary care teams that include both psychologists and physicians would help address known barriers to improved primary health care, including missed diagnoses, a lack of attention to behavioral factors and limited patient access to needed care, according to health care experts writing in a special issue of American Psychologist, the flagship journal of the American Psychological Association.

"At the heart of the new primary care team is a partnership between a primary care clinician and a psychologist or other mental health professional. The team works together ...

Small mutation changes brain freeze to hot foot

2014-05-08

DURHAM, N.C. -- Ice cream lovers and hot tea drinkers with sensitive teeth could one day have a reason to celebrate a new finding from Duke University researchers. The scientists have found a very small change in a single protein that turns a cold-sensitive receptor into one that senses heat.

Understanding sensation and pain at this level could lead to more specific pain relievers that wouldn't affect the central nervous system, likely producing less severe side effects than existing medications, said Jörg Grandl, Ph.D., an assistant professor of neurobiology in Duke's ...