(Press-News.org) AUSTIN, Texas – A new method of measuring the interaction of surface water and groundwater along the length of the Mississippi River network adds fresh evidence that the network's natural ability to chemically filter out nitrates is being overwhelmed.

The research by hydrogeologists at The University of Texas at Austin, which appears in the May 11 edition of the journal Nature Geoscience, shows for the first time that virtually every drop of water coursing through 311,000 miles (500,000 kilometers) of waterways in the Mississippi River network goes through a natural filtering process as it flows to the Gulf of Mexico.

The analysis found that 99.6 percent of the water in the network passes through filtering sediment along the banks of creeks, streams and rivers.

Such a high level of chemical filtration might sound positive, but the unfortunate implication is that the river's natural filtration systems for nitrates appear to be operating at or very close to full capacity. While further research is needed, this would make it unlikely that natural systems can accommodate the high levels of nitrates that have made their way from farmland and other sources into the river network's waterways.

As a result of its filtration systems being overwhelmed, the river system operates less as a buffer and more as a conveyor belt, transporting nitrates to the Gulf of Mexico. The amount of nitrates flowing into the gulf from the Mississippi has already created the world's second biggest dead zone, an oxygen-depleted area where fish and other aquatic life can't survive.

The research, conducted by Bayani Cardenas, associate professor of hydrogeology, and Brian Kiel, a Ph.D. candidate in geology at the university's Jackson School of Geosciences, provides valuable information to those who manage water quality efforts, including the tracking of nitrogen fertilizers used to grow crops in the Midwest, in the Mississippi River network.

"There's been a lot of work to understand surface-groundwater exchange," said Aaron Packman, a professor in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering at Northwestern University. "This is the first work putting together a physics-based estimate on the scale of one of these big rivers, looking at the net effect of nitrate removal in big river systems."

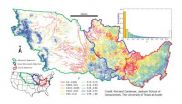

The Mississippi River network includes the Ohio River watershed on the east and the Missouri River watershed in the west as well as the Mississippi watershed in the middle.

Using detailed, ground-level data from the United States Geological Survey (USGS) and Environmental Protection Agency, Cardenas and Kiel analyzed the waterways for sinuosity (how much they bend and curve); the texture of the materials along the waterways; the time spent in the sediment (known as the hyporheic zone); and the rate at which the water flows through the sediment.

The sediment operates as a chemical filter in that microbes in the sand, gravel and mud gobble up compounds such as oxygen and nitrates from the water before the water discharges back into the stream. The more time the water spends in sediment, the more some of these compounds are transformed to potentially more environmentally benign forms.

One compound, nitrate, is a major component of inorganic fertilizers that has helped make the area encompassed by the Mississippi River network the biggest producer of corn, soybeans, wheat, cattle and hogs, in the United States.

But too much nitrogen robs water of oxygen, resulting in algal blooms and dead zones.

While the biggest source of nitrates in the Mississippi River network are industrial fertilizers, nitrates also come from animal manure, urban areas, wastewater treatment and other sources, according to USGS.

Cardenas and Kiel found that despite an image of water flowing freely downstream, nearly each drop gets caught up within the bank at one time or another. But not much of the water — only 24 percent — lingers long enough for nitrate to be chemically extracted.

The "residence times" when water entered the hyporheic zones ranged from less than an hour in the river system's headwaters to more than a month in larger, meandering channels. A previous, unrelated study of hyporheic zones found that a residence time of about seven hours is required to extract nitrogen from the water.

Cardenas said the research provides a large-scale, holistic view of the river network's natural buffering mechanism and how it is failing to operate effectively.

"Clearly for all this nitrate to make it downstream tells us that this system is very overwhelmed," Cardenas said.

The new model, he added, can be a first step to enable a wider analysis of the river system.

When a river system gets totally overwhelmed, "You lose the chemical functions, the chemical buffering," said Cardenas. "I don't know whether we're there already, but we are one big step closer to the answer now."

INFORMATION: END

Hydrologists find Mississippi River network's buffering system for nitrates is overwhelmed

New method -- the first physics-based look at the net effect of nitrate removal in the Mississippi network -- shows the filtering system operating at max capacity

2014-05-11

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Patient stem cells used to make 'heart disease-on-a-chip'

2014-05-11

Cambridge, MA—Harvard scientists have merged stem cell and 'organ-on-a-chip' technologies to grow, for the first time, functioning human heart tissue carrying an inherited cardiovascular disease. The research appears to be a big step forward for personalized medicine, as it is working proof that a chunk of tissue containing a patient's specific genetic disorder can be replicated in the laboratory.

The work, published in Nature Medicine, is the result of a collaborative effort bringing together scientists from the Harvard Stem Cell Institute, the Wyss Institute for Biologically ...

Ocean winds keep Antarctica cold, Australia dry

2014-05-11

VIDEO:

Dr. Nerlie Abram, from the Australian National University, explains why ocean winds have stopped Antarctica from warming as much as other continents. Her research also explains droughts in Southern Australia.

Click here for more information.

New Australian National University-led research has explained why Antarctica is not warming as much as other continents, and why southern Australia is recording more droughts.

Researchers have found rising levels of carbon dioxide ...

Hijacking bacteria's natural defences to trap and reveal pathogens

2014-05-11

The breakthrough, published in the journal Nature Materials, could offer an easier way of detecting pathogenic bacteria outside of a clinical setting and could be particularly important for the developing world, where access to more sophisticated laboratory techniques is often limited.

The research was led by Professor Cameron Alexander, Head of the Division of Drug Delivery and Tissue Engineering and EPSRC Leadership Fellow in the University's School of Pharmacy, building on work by PhD student Peter Magennis. Professor Alexander said: "Essentially, we have hijacked ...

UGA research examines fate of methane following the Deepwater Horizon spill

2014-05-11

Athens, Ga. – The 2010 Deepwater Horizon blowout discharged roughly five million gallons of oil and up to 500,000 tons of natural gas into Gulf of Mexico offshore waters over a period of 84 days. In the face of a seemingly insurmountable cleanup effort, many were relieved by reports following the disaster that naturally-occurring microbes had consumed much of the gas and oil.

Now, a team of researchers led by University of Georgia marine scientists have published a paper in the journal Nature Geoscience that questions this conclusion and provides evidence that microbes ...

Galectins direct immunity against bacteria that employ camouflage

2014-05-11

Our bodies produce a family of proteins that recognize and kill bacteria whose carbohydrate coatings resemble those of our own cells too closely, scientists have discovered.

Called galectins, these proteins recognize carbohydrates from a broad range of disease-causing bacteria, and could potentially be deployed as antibiotics to treat certain infections. The results are scheduled for publication in Nature Chemical Biology.

Researchers at Emory University School of Medicine made the discovery with the aid of glass slides coated with an array of over 300 different glycans ...

Study finds patients AFib at higher risk of dementia when meds out of range

2014-05-10

A new study by researchers at the Intermountain Medical Center Heart Institute in Salt Lake City has found that atrial fibrillation patients who are on blood thinning medications are at higher risk of developing dementia if their doses are not in the optimal recommended range.

The study of more than 2,600 AFib patients found they are significantly more likely to develop dementia when using medicines to prevent blood clots, such as warfarin, when their dosing is too high or too low for an extended period of time.

Findings from the study will be presented at the 2014 ...

Bee biodiversity boosts crop yields

2014-05-10

Research from North Carolina State University shows that blueberries produce more seeds and larger berries if they are visited by more diverse bee species, allowing farmers to harvest significantly more pounds of fruit per acre.

"We wanted to understand the functional role of diversity," says Dr. Hannah Burrack, an associate professor of entomology at NC State and co-author of a paper on the research. "And we found that there is a quantifiable benefit of having a lot of different types of bees pollinating a crop."

The researchers looked at blueberries in North Carolina ...

Scientists find gene behind a highly prevalent facial anomaly

2014-05-10

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. (May 9, 2014) – Whitehead Institute scientists have identified a genetic cause of a facial disorder known as hemifacial microsomia (HFM). The researchers find that duplication of the gene OTX2 induces HFM, the second-most common facial anomaly after cleft lip and palate.

HFM affects approximately one in 3,500 births. While some cases appear to run in families, no gene had been found to be causative. That is until Whitehead Fellow Yaniv Erlich and his lab set out to do just that. Their work is described in this week's issue of the journal PLOS ONE.

Patients ...

Cardiac screening test may help determine who should take aspirin to prevent heart attack

2014-05-09

MINNEAPOLIS, MN – May 6, 2014 – For over 30 years, aspirin has been known to prevent heart attacks and strokes, but who exactly should take a daily aspirin remains unclear. New research published today in Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes shows that your coronary artery calcium (CAC) score, a measurement of plaque in the arteries that feed the heart, may help determine whether or not you are a good candidate for aspirin.

"Many heart attacks and strokes occur in individuals who do not appear to be at high risk," states lead author, Michael D Miedema, MD, ...

NASA's TRMM Satellite see spring storms hit the US Great Plains

2014-05-09

VIDEO:

The TRMM satellite flew above tornado spawning thunderstorms in the southern United States on May 9, 2014 at 0115 UTC. This simulated 3-D TRMM animation shows the location of intense...

Click here for more information.

The Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission or TRMM satellite captured rainfall and cloud height information about the powerful thunderstorms and severe weather that affected the Great Plains over May 8 and 9.

Severe weather extended from Minnesota to southern ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Kidney cancer study finds belzutifan plus pembrolizumab post-surgery helps patients at high risk for relapse stay cancer-free longer

Alkali cation effects in electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction

Test platforms for charging wireless cars now fit on a bench

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

Yes! The role of YAP and CTGF as potential therapeutic targets for preventing severe liver disease

Pancreatic cancer may begin hiding from the immune system earlier than we thought

[Press-News.org] Hydrologists find Mississippi River network's buffering system for nitrates is overwhelmedNew method -- the first physics-based look at the net effect of nitrate removal in the Mississippi network -- shows the filtering system operating at max capacity