(Press-News.org) COLLEGE STATION – Sometimes we think we know everything about something only to find out we really don't, said a Texas A&M University scientist.

Dr. Kevin Conway, assistant professor and curator of fishes with Texas A&M's department of wildlife and fisheries sciences at College Station, has published a paper documenting a new species of clingfish and a startling new discovery in a second well-documented clingfish.

Smithsonian Institution

The paper, entitled "Cryptic Diversity and Venom Glands in Western Atlantic Clingfishes of the Genus Acyrtus (Teleostei: Gobiesocidae)," was published May 13 in the PLOS ONE online journal. PLOS ONE is the Public Library of Science's peer reviewed, open-access scientific journal. The full study can be viewed at http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0097664.

The scientific paper documents the study Conway and his team, including Dr. Carole Baldwin, his collaborator at the Smithsonian Institution, and Macaulay White, former Texas A&M undergraduate, have been working on for several years.

"We are excited about the study, because it resulted in not only the discovery of an undescribed species, but also the discovery of a unique venom gland in a group of fishes nobody knew were venomous," Conway said. "New groups of venomous fishes are not discovered very often, in fact the last such discovery happened back in the 1960s. The shocking thing is that the fishes that possess the venom gland have been known to science for a long time, some for over 260 years, and have been pretty well studied."

Conway said he has not been involved in a discovery of this magnitude since he joined the Texas A&M faculty.

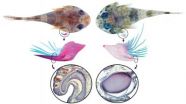

Conway said clingfishes are globally distributed at temperate and tropical latitudes, and get their name from their ability to anchor themselves using their large belly sucker. The species Conway and his team discovered is a tiny marine fish less than an inch long that lives between pieces of coral rubble in very shallow water along the coast of Belize and islands in the Caribbean and Bahamas.

"Our work shows that even in relatively well-studied areas of the world's oceans, new species can be discovered as can unknown traits in well-documented species." Conway said.

Conway explained that in order to describe a new species, taxonomists have to make comparisons with other closely related species to ensure they are not "rediscovering" something already described by another researcher.

"During that comparison process we discovered that several species of Caribbean clingfishes, but not the new one we found, have a strange gland associated with a very sharp and spine-like subopercular bone, one of four bones that support the gill covers in fishes," Conway said. "The cells inside the gland are incredibly similar to those present inside the venom glands of scorpion fishes and certain catfish and based on this similarity, we are confident that these clingfishes are also producing some type of toxin."

"Discovering a venom gland in a group of well-studied fishes that has been known to science, some for well over two centuries, is truly remarkable," Conway said.

Conway explained that most of the world's 2,000-plus venomous species of fishes deliver their venom using a modified fin ray, sharp opercular spine or even through a large fang in their lower jaw. But the venom gland they discovered in the Caribbean clingfishes associated with the subopercular gill cover bone is the first of its kind to be discovered and in fact, is unique among all venomous fish described to-date.

"We do not know exactly what the venom is used for, but based on the position of the venom gland, it is more likely that it would be used for protection, as in most venomous fishes.

"We don't yet have any information about the toxic properties of these clingfishes, but we hope that our discovery will encourage other scientists to take a look at the venom gland we discovered in more detail," he said.

Conway said clingfishes are referred to as crypto-benthic fishes which means "small, bottom dwellers."

"Crypto-benthic fishes are not commercially important, but are considered by the scientific community to play an important role in marine ecosystems, because they are likely an important food resource for larger fishes," Conway noted.

INFORMATION: END

Tiny, tenacious and tentatively toxic

Texas A&M scientist makes 2 discoveries that were hiding in plain sight

2014-05-14

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Chapman University affiliated physicist publishes on the Aharonov-Bohm effect in Nature

2014-05-14

ORANGE, Calif. – Chapman University affiliated quantum physicist Yutaka Shikano, Ph.D., has published a milestone paper in the prestigious journal Nature Communications. The title of the article is "Aharonov-Bohm effect with quantum tunneling in linear Paul trap." The Aharonov-Bohm (AB) effect was proposed by Yakir Aharonov, who is the co-director of the Institute for Quantum Studies at Chapman University, and David J. Bohm in 1959.

The AB effect showed for the first time that a magnetic field inside a confined region can have a measureable impact on a charged particle ...

Simplifying an ultrafast laser offers better control

2014-05-14

This news release is available in French. Going back to the drawing board to find a way to overcome the technical limitations of their laser, a team led by François Légaré, professor at the INRS Énergie Matériaux Télécommunications Research Centre, developed a new concept offering a simpler laser design, control over new parameters, and excellent performance potential. Called "frequency domain optical parametric amplification" (FOPA), the concept supersedes traditional time domain amplification schemes that have been the linchpin of ultrafast laser science for 20 years. ...

Magnetar formation mystery solved?

2014-05-14

When a massive star collapses under its own gravity during a supernova explosion it forms either a neutron star or black hole. Magnetars are an unusual and very exotic form of neutron star. Like all of these strange objects they are tiny and extraordinarily dense — a teaspoon of neutron star material would have a mass of about a billion tonnes — but they also have extremely powerful magnetic fields. Magnetar surfaces release vast quantities of gamma rays when they undergo a sudden adjustment known as a starquake as a result of the huge stresses in their crusts.

The Westerlund ...

Microchip-like technology allows single-cell analysis

2014-05-14

VIDEO:

This is a microscopic view of the new microchip-like technology sorting and storing magnetic particles in a three-by-three array.

Click here for more information.

DURHAM, N.C. -- A U.S. and Korean research team has developed a chip-like device that could be scaled up to sort and store hundreds of thousands of individual living cells in a matter of minutes. The system is similar to a random access memory chip, but it moves cells rather than electrons.

Researchers at ...

Using nature as a model for low-friction bearings

2014-05-14

Lubricants are required wherever moving parts come together. They prevent direct contact between solid elements and ensure that gears, bearings, and valves work as smoothly as possible. Depending on the application, the ideal lubricant must meet conflicting requirements. On the one hand, it should be as thin as possible because this reduces friction. On the other hand, it should be viscous enough that the lubricant stays in the contact gap. In practice, grease and oils are often used because their viscosity increases with pressure.

Biological lubrication in contrast is ...

Early menopause ups heart failure risk, especially for smokers

2014-05-14

CLEVELAND, Ohio (May 14, 2014)—Women who go through menopause early—at ages 40 to 45—have a higher rate of heart failure, according to a new study published online today in Menopause, the journal of The North American Menopause Society (NAMS). Smoking, current or past, raises the rate even more.

Research already pointed to a relationship between early menopause and heart disease—usually atherosclerotic heart disease. But this study from the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, Sweden, is the first to demonstrate a link with heart failure, the inability of the heart to pump ...

Virginia Tech updates football helmet ratings, 5 new helmets meet 5-star mark

2014-05-14

Virginia Tech has updated results of its adult football helmet ratings, which are designed to identify key differences between the abilities of individual helmets to reduce the risk of concussion.

All five of the new adult football helmets introduced this spring earned the five-star mark, which is the highest rating awarded by the Virginia Tech Helmet Ratings™. The complete ratings of the helmets manufactured by Schutt Sports and Xentih LLC, each with two new products, and Rawlings Sporting Goods Co., with one helmet, are publicly available at the helmet ratings website.

The ...

Primates and patience -- the evolutionary roots of self control

2014-05-14

Lincoln, Neb., May 14, 2014 – A chimpanzee will wait more than two minutes to eat six grapes, but a black lemur would rather eat two grapes now than wait any longer than 15 seconds for a bigger serving.

It's an echo of the dilemma human beings face with a long line at a posh restaurant. How long are they willing to wait for the five-star meal? Or do they head to a greasy spoon to eat sooner?

A paper published today in the scientific journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B explores the evolutionary reasons why some primate species wait for a ...

Human learning altered by electrical stimulation of dopamine neurons

2014-05-14

PHILADELPHIA - Stimulation of a certain population of neurons within the brain can alter the learning process, according to a team of neuroscientists and neurosurgeons at the University of Pennsylvania. A report in the Journal of Neuroscience describes for the first time that human learning can be modified by stimulation of dopamine-containing neurons in a deep brain structure known as the substantia nigra. Researchers suggest that the stimulation may have altered learning by biasing individuals to repeat physical actions that resulted in reward.

"Stimulating the substantia ...

Hospital rankings for heart failure readmissions unaffected by patient's socioeconomic status

2014-05-13

A new report by Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, published in the journal Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes, shows the socioeconomic status of congestive heart failure patients does not influence hospital rankings for heart failure readmissions.

In the study, researchers assessed whether adding a standard measure for indicating the socioeconomic status of heart failure patients could alter the expected 30-day heart failure hospital risk standardized readmission rate (RSRR) among New York City hospitals. For each patient a standard socioeconomic ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

The Lancet: First-ever in-utero stem cell therapy for fetal spina bifida repair is safe, study finds

Nanoplastics can interact with Salmonella to affect food safety, study shows

Eric Moore, M.D., elected to Mayo Clinic Board of Trustees

NYU named “research powerhouse” in new analysis

New polymer materials may offer breakthrough solution for hard-to-remove PFAS in water

Biochar can either curb or boost greenhouse gas emissions depending on soil conditions, new study finds

Nanobiochar emerges as a next generation solution for cleaner water, healthier soils, and resilient ecosystems

Study finds more parents saying ‘No’ to vitamin K, putting babies’ brains at risk

Scientists develop new gut health measure that tracks disease

Rice gene discovery could cut fertiliser use while protecting yields

Jumping ‘DNA parasites’ linked to early stages of tumour formation

Ultra-sensitive CAR T cells provide potential strategy to treat solid tumors

Early Neanderthal-Human interbreeding was strongly sex biased

North American bird declines are widespread and accelerating in agricultural hotspots

Researchers recommend strategies for improved genetic privacy legislation

How birds achieve sweet success

More sensitive cell therapy may be a HIT against solid cancers

Scientists map how aging reshapes cells across the entire mammalian body

Hotspots of accelerated bird decline linked to agricultural activity

How ancient attraction shaped the human genome

NJIT faculty named Senior Members of the National Academy of Inventors

App aids substance use recovery in vulnerable populations

College students nationwide received lifesaving education on sudden cardiac death

Oak Ridge National Laboratory launches the Next-Generation Data Centers Institute

Improved short-term sea level change predictions with better AI training

UAlbany researchers develop new laser technique to test mRNA-based therapeutics

New water-treatment system removes nitrogen, phosphorus from farm tile drainage

Major Canadian study finds strong link between cannabis, anxiety and depression

New discovery of younger Ediacaran biota

Lymphovenous bypass: Potential surgical treatment for Alzheimer's disease?

[Press-News.org] Tiny, tenacious and tentatively toxicTexas A&M scientist makes 2 discoveries that were hiding in plain sight