(Press-News.org) A National Institutes of Health-sponsored study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) showed that lorazepam - a widely used but not yet Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved drug for children - is no more effective than an approved benzodiazepine, diazepam, for treating pediatric status epilepticus.

Status epilepticus is a state in which the brain is in a persistent state of seizure. By the age of 15, 4 to 8 percent of children experience a seizure episode, which can be life threatening if they aren't stopped immediately. Status epilepticus is a continuous, unremitting seizure lasting longer than five minutes or recurrent seizures without regaining consciousness between seizures for more than five minutes.

Before this current study, published April 23, there was no evidence indicating which of the two treatments might prove more effective. Although it is not yet approved by the FDA, James M. Chamberlain, MD, Division Chief of Emergency Medicine at Children's National Health System, the study's principal investigator, estimates that lorazepam is used as first-line therapy in most emergency departments.

"The study results provide reassurance to emergency medicine personnel who must act within minutes," said Chamberlain. The study was conducted at 11 hospitals in the United States using the infrastructure of the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN), under a contract from the National Institutes of Health's (NIH) Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD).

Both lorazepam and diazepam are used to treat status epilepticus. Diazepam, also known as Valium, is the only one of the two drugs to have been approved by the FDA for use in adults and children.

Lorazepam, marketed under the trade name Ativan, has been approved by the FDA only for use in adults. Once the FDA has approved a drug for use in adults, physicians may then prescribe it for other uses and in pediatric patients if, in their best judgment, they believe their patients will benefit.

"Sometimes physicians are forced to rely on their best judgment alone," said George Giacoia, MD, of the NICHD's Obstetric and Pediatric Pharmacology and Therapeutics Branch. "However, it's always better to make treatment decisions on the evidence that comes only from conducting large comparison studies. We now know that lorezapam offers no advantage over diazepam in treating pediatric seizure disorder, and that diazepam is more suited to use by emergency teams."

In 2007, the National Institutes of Health's Pediatric Seizure study sought to determine which of two drugs—diazepam or lorazepam—was more effective in treating the life-threatening condition, status epilepticus. This condition can occur without warning. For reasons not fully understood, a child may be gripped by continuous seizures, which, if not stopped within minutes, may lead to brain damage or even death.

Because of the random nature of seizures and their significantly life altering affects, lorezapam is commonly prescribed to treat status epilepticus in children, even though it hasn't been specifically approved for that use. The results of the Pediatric Seizure study do not support the use of lorezapam instead of diazepam for treating status epilepticus, Dr. Chamberlain said. Also, because lorezapam needs to be refrigerated and diazepam does not, diazepam is more suited for use by ambulance crews.

A few previous studies indicated that lorazepam might be more effective at ending a seizure and might be less likely than diazepam to depress breathing—a side effect of benzodiazapines, the category of medications that includes both drugs.

In their study, Chamberlain and colleague wrote, "There is no conclusive evidence to support lorazepam as a superior treatment and there is little consensus as to which is the preferred agent."

The current study was the largest, most comprehensive comparison study of the two treatments for pediatric seizure disorder. Dr. Chamberlain and his colleagues enrolled 310 children at the 11 institutions, between 2008 and 2012. The researchers found that both medications successfully halted seizures in 70 percent of cases, and each had rates of severe respiratory depression of less than 20 percent.

It's important that "we get the most important scientific information about such medications so there are government approvals for pediatric use," Chamberlain said. "Pediatric patients are not just small adults."

INFORMATION:

The Pediatric Seizure study was funded in accordance with the Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act. Under provisions of the law, the NIH consults with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to determine which drugs – previously approved by the FDA for use in adults –should be prioritized for further testing in children.

Contact: Emily Hartman or Joe Cantlupe at 202-476-4500.

About Children's National Health System

Children's National Health System, based in Washington, DC, has been serving the nation's children since 1870. Children's National's hospital is Magnet® designated, and is consistently ranked among the top pediatric hospitals by U.S. News & World Report. Home to the Children's Research Institute and the Sheikh Zayed Institute for Pediatric Surgical Innovation, Children's National is one of the nation's top NIH-funded pediatric institutions. With a community-based pediatric network, eight regional outpatient centers, an ambulatory surgery center, two emergency rooms, an acute care hospital, and collaborations throughout the region, Children's National is recognized for its expertise and innovation in pediatric care and as an advocate for all children. For more information, visit ChildrensNational.org, or follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

Widely used drug no more effective than FDA approved medication in treating epileptic seizures

2014-05-14

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

In the wake of high-profile battery fires, a safer approach emerges

2014-05-14

As news reports of lithium-ion battery (LIB) fires in Boeing Dreamliner planes and Tesla electric cars remind us, these batteries — which are in everyday portable devices, like tablets and smartphones — have their downsides. Now, scientists have designed a safer kind of lithium battery component that is far less likely to catch fire and still promises effective performance. They report their approach in the Journal of the American Chemical Society.

Lynden Archer, Geoffrey Coates and colleagues at Cornell University explain that the danger of LIBs originates with their ...

Relationship satisfaction linked with changing use of contraception

2014-05-14

Women's sexual satisfaction in long-term heterosexual relationships may be influenced by changes in hormonal contraceptive use, research from the University of Stirling shows.

The study, published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science, was carried out by researchers from the universities of Stirling, Glasgow, Newcastle, Northumbria and Charles University in Prague.

The team looked at a sample of 365 couples, and investigated how satisfaction levels – in both sexual and non-sexual aspects of long-term relationships – were influenced ...

A new approach to treating peanut and other food allergies

2014-05-14

These days, more and more people seem to have food allergies, which can sometimes have life-threatening consequences. In ACS' Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, scientists report the development of a new type of flour that someday could be used in food-based therapies to help people better tolerate their allergy triggers, including peanuts.

Mary Ann Lila and colleagues note that of the 170 foods that cause allergic reactions, peanuts can be the most dangerous. These reactions can range from mild itching and hives to life-threatening anaphylactic shock, in which ...

Extinct relative helps to reclassify the world's remaining 2 species of monk seal

2014-05-14

The recently extinct Caribbean monk seal (Monachus tropicalis) was one of three species of monk seal in the world. Its relationship to the Mediterranean and Hawaiian monk seals, both living but endangered, has never been fully understood. Through DNA analysis and skull comparisons, however, Smithsonian scientists and colleagues have now clarified the Caribbean species' place on the seal family tree and created a completely new genus. The team's findings are published in the scientific journal ZooKeys.

First reported by Columbus in 1494, the Caribbean monk seal ranged ...

Research reveals New Zealand sea lion is a relative newcomer

2014-05-14

The modern New Zealand sea lion is a relative newcomer to our mainland, replacing a now-extinct, unique prehistoric New Zealand sea-lion that once lived here, according to a new study.

A team of biologists from New Zealand's University of Otago estimates that this prehistoric mainland sea-lion population became extinct as recently as 600 years ago, and was then replaced by a lineage previously limited to the waters of the cold subantarctic.

The Marsden-funded study, carried out by Otago Zoology PhD student Catherine Collins, and led by Professor Jon Waters, set out ...

New technology simplifies production of biotech medicines

2014-05-14

The final step in the production of a biotech medicine is finishing with the correct sugar structure. This step is essential for the efficacy of the medicine, but it also makes the production process very complex and expensive. Leander Meuris, Francis Santens and Nico Callewaert (VIB/UGent) have developed a technology that shortens the sugar structures whilst retaining the therapeutic efficiency. This technology has the potential to make the production of biotech medicines significantly simpler and cheaper.

Sugar structures are essential for the mechanism of biotech ...

@millennials wary of @twitter, #MSU study finds

2014-05-14

EAST LANSING, Mich. --- A new study indicates young adults have a healthy mistrust of the information they read on Twitter.

Nearly anyone can start a Twitter account and post 140 characters of information at a time, bogus or not, a fact the study's participants seemed to grasp, said Kimberly Fenn, assistant professor of psychology at Michigan State University.

"Our findings suggest young people are somewhat wary of information that comes from Twitter," said Fenn, lead investigator on the study. "It's a good sign."

The study, funded by the National Science Foundation, ...

Prevent premature deaths from heart failure, urges the Heart Failure Association

2014-05-14

Athens, 14 May 2014. The Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) is calling for global policy change relating to heart failure. An international white paper, Heart failure: preventing disease and death worldwide, will be presented at an endorsement event on 16 May 2014 in Athens, Greece, immediately before the Heart Failure 2014 Congress.

Approximately 15 million people are living with heart failure in Europe,1 and 26 million worldwide.2 The outlook is poor: survival rates are worse than those for bowel, breast or prostate cancer, and ...

Understanding the 1918 flu pandemic can aid in better infectious disease response

2014-05-14

COLUMBIA, Mo. – The 1918 Flu Pandemic infected over 500 million people, killing at least 50 million. Now, a researcher at the University of Missouri has analyzed the pandemic in two remote regions of North America, finding that despite their geographical divide, both regions had environmental, nutritional and economic factors that influenced morbidity during the pandemic. Findings from the research could help improve current health policies.

"Epidemics such as the Black Death in the 14th century, cholera in the 19th century and malaria have been documented and recorded ...

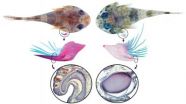

Tiny, tenacious and tentatively toxic

2014-05-14

COLLEGE STATION – Sometimes we think we know everything about something only to find out we really don't, said a Texas A&M University scientist.

Dr. Kevin Conway, assistant professor and curator of fishes with Texas A&M's department of wildlife and fisheries sciences at College Station, has published a paper documenting a new species of clingfish and a startling new discovery in a second well-documented clingfish.

Smithsonian Institution

The paper, entitled "Cryptic Diversity and Venom Glands in Western Atlantic Clingfishes of the Genus Acyrtus (Teleostei: Gobiesocidae)," ...