(Press-News.org) MADISON, Wis. — The latitude at which tropical cyclones reach their greatest intensity is gradually shifting from the tropics toward the poles at rates of about 33 to 39 miles per decade, according to a study published today (May 14, 2014) in the journal Nature.

The new study was led by Jim Kossin, a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) National Climatic Data Center scientist stationed at the University of Wisconsin-Madison's Cooperative Institute for Meteorological Satellite Studies. The research documents a poleward migration of storm intensity in both the Northern and Southern Hemispheres through an analysis of 30 years of global historical tropical cyclone data. The term "tropical cyclone" describes a broad category of storms that includes hurricanes and typhoons, large and damaging storms that draw their energy from warm ocean waters.

The findings are important, says Kossin, because they suggest that some areas, including densely populated coastal cities, could experience changes in risk due to large storms and associated floods and storm surges. Regions closer to the equator, he notes, could experience a reduced risk, and places more distant from the equator could experience an increased risk. The trend observed by Kossin and his colleagues is particularly important given the devastating loss of life and property that can follow in the wake of a tropical cyclone.

Conversely, equatorial regions where people depend on tropical cyclone rainfall to replenish sources of fresh water may experience water shortages.

According to Kossin, there isn't a global trend in the frequency of tropical cyclones for the 30-year study period. However, the data record shows a distinct poleward trend in the observed latitude where storms are the most intense. While estimates of storm intensity vary in the data, the latitude at which tropical cyclones reach their maximum intensity, Kossin explains, is a more reliable assessment of changes in the way tropical cyclones behave.

"We've identified changes in the environment in which the deep tropics have become more hostile to the formation and intensification of tropical cyclones and the higher latitudes have become less hostile," Kossin explains. "This seems to be driving the poleward migration" of storm intensity.

From a global climate perspective, Kossin says, "the more compelling aspect is that the rate of migration fits very well into independent estimates of the observed expansion of the tropics." That phenomenon has been widely studied by other scientists and is attributed, in part, to increasing greenhouse gases, stratospheric ozone depletion, and particulate pollution, all by-products of human activity.

Whether the observed movement of tropical cyclone maximum intensity toward the poles is a result of the expansion of the tropics and its links to human activity requires more and longer-term investigation, says Kossin. Both phenomena, however, exhibit very similar behavior over the past 30 years, lending credence to the idea that the two are linked.

INFORMATION:

Co-authors on the Nature paper are Kerry A. Emanuel, Program in Atmospheres, Oceans and Climate at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Gabriel A. Vecchi, NOAA Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory, Princeton, New Jersey.

—Jean Phillips, 608-262-8164, jeanp@ssec.wisc.edu

Study shows tropical cyclone intensity shifting poleward

2014-05-14

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

NIH takes action on sex/gender in cell and animal studies

2014-05-14

What:

NIH leadership is available to answer questions from reporters about new policies that will be published online Wednesday in Nature to ensure that sex is treated as a fundamental variable in the preclinical biomedical research that it funds.

Article: NIH takes action on sex/gender in cell and animal studies. Nature. Clayton, J.A. & Collins, F.S.. Published online May 14, 2014.

Spokesperson:

Janine Austin Clayton, M.D., NIH Associate Director for Research on Women's Health, Director for the NIH Office of Research on Women's Health

INFORMATION:

Contact: To ...

Study: Dangerous storms peaking further north, south than in past

2014-05-14

Powerful, destructive tropical cyclones are now reaching their peak intensity farther from the equator and closer to the poles, according to a new study co-authored by an MIT scientist.

The results of the study, published today in the journal Nature, show that over the last 30 years, tropical cyclones — also known as hurricanes or typhoons — are moving poleward at a rate of about 33 miles per decade in the Northern Hemisphere and 38 miles per decade in the Southern Hemisphere.

"The absolute value of the latitudes at which these storms reach their maximum intensity seems ...

Possible new plan of attack for opening and closing the blood-brain barrier

2014-05-14

Like a bouncer at an exclusive nightclub, the blood-brain barrier allows only select molecules to pass from the bloodstream into the fluid that bathes the brain. Vital nutrients get in; toxins and pathogens are blocked. The barrier also ensures that waste products are filtered out of the brain and whisked away.

The blood-brain barrier helps maintain the delicate environment that allows the human brain to thrive. There's just one problem: The barrier is so discerning, it won't let medicines pass through. Researchers haven't been able to coax it to open up because they ...

Tropical cyclone 'maximum intensity' is shifting toward poles

2014-05-14

Over the past 30 years, the location where tropical cyclones reach maximum intensity has been shifting toward the poles in both the northern and southern hemispheres at a rate of about 35 miles, or one-half a degree of latitude, per decade according to a new study, The Poleward Migration of the Location of Tropical Cyclone Maximum Intensity, published tomorrow in Nature.

As tropical cyclones move into higher latitudes, some regions closer to the equator may experience reduced risk, while coastal populations and infrastructure poleward of the tropics may experience increased ...

Researchers discover how DHA omega-3 fatty acid reaches the brain

2014-05-14

It is widely believed that DHA (docosahexaenoic acid) is good for your brain, but how it is absorbed by the brain has been unknown. That is - until now. Researchers from Duke-NUS Graduate Medical School Singapore (Duke-NUS) have conducted a new study identifying that the transporter protein Mfsd2a carries DHA to the brain. Their findings have widespread implications for how DHA functions in human nutrition.

People know that DHA is an essential dietary nutrient that they can get from seafood and marine oils. Baby formula companies are especially attuned to the benefits ...

California mountains rise as groundwater depleted in state's Central Valley

2014-05-14

Winter rains and summer groundwater pumping in California's Central Valley make the Sierra Nevada and Coast Ranges sink and rise by a few millimeters each year, creating stress on the state's earthquake faults that could increase the risk of a quake.

Gradual depletion of the Central Valley aquifer because of groundwater pumping also raises these mountain ranges by a similar amount each year – about the thickness of a dime – with a cumulative rise over the past 150 years of up to 15 centimeters (6 inches), according to calculations by a team of geophysicists.

While the ...

CEBAF beam goes over the hump: Highest-energy beam ever delivered at Jefferson Lab

2014-05-14

The Continuous Electron Beam Accelerator Facility (CEBAF) at the U.S. Department of Energy's Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility has achieved the final two accelerator commissioning milestones needed for approval to start experimental operations following its first major upgrade.

In the early hours of May 7, the machine delivered its highest-energy beams ever, 10.5 billion electron-volts (10.5 GeV) through the entire accelerator and up to the start of the beamline for its newest experimental complex, Hall D. Then, in the last minutes of the day on May 7, the ...

Who should be saved? Study gets diverse MD community views on healthcare disaster planning

2014-05-14

BALTIMORE—In the event of a flu pandemic, who should have priority access to life-saving ventilators, and who should make that determination? Few disaster preparedness plans have taken community values regarding allocation into account, but a new study is aiming to change that through public engagement with Maryland residents.

"In the event of a healthcare crisis, understanding the community perspective and having citizen buy-in will be critical to avoid compounding the initial disaster with further social upheaval," says principal investigator Elizabeth L. Daugherty ...

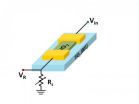

Strongly interacting electrons in wacky oxide synchronize to work like the brain

2014-05-14

Current computing is based on binary logic -- zeroes and ones -- also called Boolean computing, but a new type of computing architecture stores information in the frequencies and phases of periodic signals and could work more like the human brain using a fraction of the energy necessary for today's computers, according to a team of engineers.

Vanadium dioxide is called a "wacky oxide" because it transitions from a conducting metal to an insulating semiconductor and vice versa with the addition of a small amount of heat or electrical current. A device created by electrical ...

Research shows hope for normal heart function in children with fatal heart disease

2014-05-14

DETROIT, Mich., - After two decades of arduous research, a National Institutes of Health (NIH)-funded investigator at the Children's Hospital of Michigan (CHM) at the Detroit Medical Center (DMC) and the Wayne State University School of Medicine has published a new study showing that many children with an often fatal type of heart disease can recover "normal size and function" of damaged sections of their hearts.

The finding by Children's Hospital of Michigan's Pediatrician-in-Chief and Wayne State University Chair of Pediatrics Steven E. Lipshultz, M.D., F.A.A.P., F.A.H.A., ...