(Press-News.org) A commonly prescribed antidepressant can reduce production of the main ingredient in Alzheimer's brain plaques, according to new research at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and the University of Pennsylvania.

The findings, in mice and people, are published May 14 in Science Translational Medicine. They support preliminary mouse studies that evaluated a variety of antidepressants.

Brain plaques are tied closely to memory problems and other cognitive impairments caused by Alzheimer's disease. Stopping plaque buildup may halt the disastrous mental decline caused by the disorder.

The scientists found that the antidepressant citalopram stopped the growth of plaques in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. And in young adults who were cognitively healthy, a single dose of the antidepressant lowered by 37 percent the production of amyloid beta, the primary ingredient in plaques.

Although the findings are encouraging, the scientists caution that it would be premature for people to take antidepressants solely to slow the development of Alzheimer's disease.

"Antidepressants appear to be significantly reducing amyloid beta production, and that's exciting," said senior author John Cirrito, PhD, assistant professor of neurology at Washington University. "But while antidepressants generally are well tolerated, they have risks and side effects. Until we can more definitively prove that these drugs help slow or stop Alzheimer's in humans, the risks aren't worth it. There is still much more work to do."

Amyloid beta is a protein produced by normal brain activity. Levels of this protein rise in the brains of patients with Alzheimer's, causing it to clump together into plaques. Plaques also are sometimes present in cognitively normal brains.

Cirrito's earlier research had shown that serotonin, a chemical messenger in the brain, reduces amyloid beta production. First author Yvette Sheline, MD, also has linked treatment with antidepressants to reduced plaque levels in cognitively healthy individuals.

Most antidepressants keep serotonin circulating in the brain, so this led Cirrito and Sheline to wonder whether the drugs block the increase of amyloid beta levels and slow the progression of Alzheimer's.

In 2011, the researchers tested several antidepressants in young mice genetically altered to develop Alzheimer's disease as they aged. In these mice, which had not yet developed brain plaques, antidepressants reduced amyloid beta production by an average of 25 percent after 24 hours.

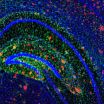

For the new study, the team gave citalopram to older mice with brain plaques. Jin-Moo Lee, MD, PhD, professor of neurology, used a technique called two-photon imaging to track the growth of Alzheimer's-like plaques in the mice for 28 days. Giving the mice the antidepressant stopped the growth of existing plaques and reduced the formation of new plaques by 78 percent.

In a second experiment, the scientists gave a single dose of citalopram to 23 people ages 18 to 50 who were not cognitively impaired or depressed. Samples of spinal fluid taken from the participants over the next 24 hours showed a 37 percent drop in amyloid beta production.

Now the researchers are trying to learn the molecular details of how serotonin affects amyloid beta production in mouse models.

"We also plan to study older adults who will be treated for two weeks with antidepressants," said Sheline, who is now at the University of Pennsylvannia. "If we see a drop in levels of amyloid beta in their spinal fluid after two weeks, then we will know that this beneficial reduction in amyloid beta is sustainable."

INFORMATION:

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R21 AG03969002 (Y.I.S.), R01 AG04150202 (Y.I.S.), NIH R01 AG042513 (J.R.C.), R21 NS082529 (J.-M.L.) and R01 NS067905 (J.-M.L.); Washington University Hope Center for Neurological Diseases (Y.I.S. and J.-M.L.); and Washington University Biomedical Mass Spectrometry Resource (P41 GM103422, P60 DK020579, and P30 DK056341).

Sheline YI, West T, Yarasheski K, Swarm R, Jasielec MS, Fisher JR, Ficker WD, Yan P, Xiong C, Frederiksen C, Grzelak MV, Chott R, Bateman RJ, Morris JC, Mintun MA, Lee J-M, Cirrito JR. An antidepressant decreases CSF Ab production in healthy individuals and in transgenic AD mice. Science Translational Medicine, online May 14, 2014.

Washington University School of Medicine's 2,100 employed and volunteer faculty physicians also are the medical staff of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children's hospitals. The School of Medicine is one of the leading medical research, teaching and patient-care institutions in the nation, currently ranked sixth in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children's hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.

Antidepressant may slow Alzheimer's disease

2014-05-14

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Can anti-depressants help prevent Alzheimer's disease?

2014-05-14

PHILADELPHIA – A University of Pennsylvania researcher has discovered that the common selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) citalopram arrested the growth of amyloid beta, a peptide in the brain that clusters in plaques that are thought to trigger the development of Alzheimer's disease (AD). Penn, in collaboration with investigators at Washington University, tested the drug's effects on the brain interstitial fluid (ISF) in plaque-bearing mice and the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of healthy human subjects to draw its conclusions, which are detailed in the new issue ...

Hitting a moving target

2014-05-14

LA JOLLA, CA—May 14, 2014—A vaccine or other therapy directed at a single site on a surface protein of HIV could in principle neutralize nearly all strains of the virus—thanks to the diversity of targets the site presents to the human immune system.

The finding, from a study led by scientists at The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI), is likely to influence future designs for HIV vaccines and antibody-based therapies.

"We found, for example, that if the virus tries to escape from an antibody directed at that site by eliminating one of its sugars, the antibody often ...

Deformable mirror corrects errors

2014-05-14

This news release is available in German.

Lasers are used in manufacturing to cut materials or weld components together. Laser light is focused to a point using various lenses and mirrors; the smaller the focal point and the higher the energy, the more accurately operators can work with the laser. So, turn up the power and off you go, right? It is not that simple because when laser power increases, the mirror heats up accordingly, causing it to deform. A deformed mirror cannot effectively focus the laser; the focal point gets bigger and laser power falls away.

Precisely ...

Victims want to change, not just punish, offenders

2014-05-14

Revenge is a dish best served with a side of change.

A series of experiments conducted by researchers affiliated with Princeton University has found that punishment is only satisfying to victims if the offenders change their attitude as a result of the punishment.

"Revenge is only 'sweet' if the person reacts with a change in attitude, if the person understands that what they did was wrong. It is not the act itself that makes punishment satisfying," said Friederike Funk, a Princeton graduate student in psychology and one of the researchers.

The findings offer insights ...

Study shows breastfeeding, birth control may reduce ovarian cancer risk in women with BRCA mutations

2014-05-14

PHILADELPHIA — Breastfeeding, tubal ligation – also known as having one's "tubes tied" – and oral contraceptives may lower the risk of ovarian cancer for some women with BRCA gene mutations, according to a comprehensive analysis from a team at the University of Pennsylvania's Basser Research Center for BRCA and the Abramson Cancer Center. The findings, a meta-analysis of 44 existing peer-reviewed studies, are published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

The researchers, from Penn's Perelman School of Medicine, found that breastfeeding and tubal ligation ...

New insight into thermoelectric materials may boost green technologies

2014-05-14

Coral Gables, Fla. (May 15, 2014) — Thermoelectric materials can turn a temperature difference into an electric voltage. Among their uses in a variety of specialized applications: generating power on space probes and cooling seats in fancy cars.

University of Miami (UM) physicist Joshua Cohn and his collaborators report new surprising properties of a metal named lithium purple-bronze (LiPB) that may impact the search for materials useful in power generation, refrigeration, or energy detection. The findings are published in the journal Physical Review Letters.

"If current ...

SapC-DOPS technology may help with imaging brain tumors, research shows

2014-05-14

Just because you can't see something doesn't mean it's not there.

Brain tumors are an extremely serious example of this and are not only difficult to treat—both adult and pediatric patients have a five-year survival rate of only 30 percent—but also have even been difficult to image, which could provide important information for deciding next steps in the treatment process.

However, Cincinnati Cancer Center and University of Cincinnati Cancer Institute research studies published in an April online issue of the Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging and a May issue of ...

How cone snail venom minimizes pain

2014-05-14

The venom from marine cone snails, used to immobilize prey, contains numerous peptides called conotoxins, some of which can act as painkillers in mammals. A recent study in The Journal of General Physiology provides new insight into the mechanisms by which one conotoxin, Vc1.1, inhibits pain. The findings help explain the analgesic powers of this naturally occurring toxin and could eventually lead to the development of synthetic forms of Vc1.1 to treat certain types of neuropathic pain in humans.

Neuropathic pain, a form of chronic pain that occurs in conjunction with ...

Scientists test hearing in Bristol Bay beluga whale population

2014-05-14

The ocean is an increasingly industrialized space. Shipping, fishing, and recreational vessels, oil and gas exploration and other human activities all increase noise levels in the ocean and make it more difficult for marine mammals to hear and potentially diminish their range of hearing.

"Hearing is the main way marine mammals find their way around the ocean," said Aran Mooney, a biologist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI). It's important to know whether and to what extent human activity is negatively impacting them.

But how can we get marine mammals living ...

Snubbing lion hunters could preserve the endangered animals

2014-05-14

For hundreds of years young men from some ethnic groups in Tanzania,

called "lion dancers" because they elaborately acted out their lion

killing for spectators, were richly rewarded for killing lions that

preyed on livestock and people. Now when a lion dancer shows up he

might be called a rude name rather than receive a reward, according

to a new UC Davis study.

Some villagers are snubbing the lion killers, calling them "fakers"

and contemplating punishing them and those who continue to reward

them, said Monique Borgerhoff Mulder, anthropology professor at UC

Davis. ...