(Press-News.org) COLLEGE STATION – A team of Texas A&M University System scientists have investigated how "body clock dysregulation" might affect obesity-related metabolic disorders.

The team was led by Dr. Chaodong Wu, associate professor in the department of nutrition and food sciences of Texas A&M's College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, and Dr. David Earnest, professor in the department of neuroscience and experimental therapeutics, Texas A&M Health Science Center.

Study results were published recently on the Journal of Biological Chemistry website at http://www.jbc.org/content/early/2014/04/25/jbc.M113.539601.

"Animal sleeping and eating patterns, including those of humans, are subject to a circadian rhythmicity," Earnest said. "And previous studies have shown an association between the dysregulation of circadian or body clock rhythms and some metabolic disorders."

Wu said circadian clocks in peripheral tissues and cells drive daily rhythms and coordinate many physiological processes, including inflammation and metabolism.

"And recent scientific observations suggest that disruption of circadian clock regulation plays a key role in the development of metabolic diseases, including obesity and diabetes," he noted.

He said this study affirms that eating unhealthy foods causes health problems and that it's much worse to eat unhealthy foods at the wrong time. It also indicates that "time-based treatment may provide better management of metabolic diseases.

"To promote human health, we need not only to eat healthy foods, but also more importantly to keep a healthy lifestyle, which includes avoiding sleeping late and eating at night," he said.

Wu and Earnest said while previous studies using mice with genetic mutation of the removal of core clock genes has indicated that specific disruption of circadian clock function alters metabolism or produces obesity, the mechanism remained unknown. As key components of inflammation in obesity, macrophages, which are immune cells, contain cell-autonomous circadian clocks that have been shown to gate inflammatory responses.

"Our hypothesis was that overnutrition causes circadian clock dysregulation, which induces pro-inflammatory activity in adipose tissue. This then worsens inflammation and fat deposition, leading to systematic insulin resistance," Wu said.

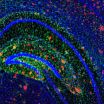

To test the hypothesis, the team conducted experiments with "reporter mice" in which the circadian rhythmicity of various types of cells could be monitored by looking at their reporter activity. Accordingly, the reporter mice were put on a 12-hour light-dark cycle and were fed a high-fat diet. Additional reporter mice were fed a low-fat diet and served as controls. In this set of experiments, the team was able to characterize the effects of a high-fat diet on circadian clock rhythmicity and inflammatory responses in immune cells, or macrophages.

To further define a unique role for circadian clock dysregulation in metabolic disorders, the team conducted "bone marrow transplantation" experiments, through which the rhythmicity of circadian clocks was disrupted only in a specific type of immune cells. After high-fat diet feeding, the transplanted mice were used for collection of blood and tissue samples. A number of physiological and immunological assays also were performed on the mice.

Earnest said results showed that during obesity, that is when mice were fed a high-fat diet, the rhythmicity of circadian clocks in immune cells of fat tissue is dysregulated by a prolonged rhythmic period. This is, in turn, is linked to increased accumulation of immune cells in fat tissue and decreased whole-body insulin sensitivity.

"Animals on a high-fat diet display metabolic problems associated with obesity," Earnest said. "The problems are worsened in animals whose circadian clocks in immune cells are disrupted."

Earnest and Wu said the study will help those involved in human health and nutrition better understand the underlying mechanisms related to obesity and diabetes.

INFORMATION:

Texas A&M-led study shows how 'body clock' dysregulation underlies obesity, more

2014-05-14

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

A better way to treat ACE inhibitor angioedema in the ED

2014-05-14

CINCINNATI—Investigators at the University of Cincinnati have found a safe and effective treatment for life-threatening angioedema attacks in the emergency department.

In angioedema, patients experience a rapid swelling of the skin and subcutaneous tissues—which, in some cases, can lead to airway obstruction and suffocation. Physicians usually treat angioedema like an allergic reaction with corticosteroids and antihistamines.

But that therapy doesn't always work for another version of the condition, thought to be caused by taking a class of drugs known as ACE inhibitors. ...

Obesity associated with longer hospital stays, higher costs in total knee replacement patients

2014-05-14

ROSEMENT, Ill.─ Obesity is associated with longer hospital stays and higher costs in total knee replacement (TKR) patients, independent of whether or not the patient has an obesity-related disease or condition (comorbidity), according to a new study published in the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (JBJS).

More than half of TKR patients have a body mass index (BMI) within the obesity range (greater than 30 kg/m²), which has been linked to a higher risk for related comorbidities such as diabetes, hypertension, osteoarthritis; and in some studies, to higher medical ...

California Central Valley groundwater depletion slowly raises Sierra Nevada mountains

2014-05-14

Winter rains and summer groundwater pumping in California's Central Valley make the Sierra Nevada and Coast Mountain Ranges sink and rise by a few millimeters each year, creating stress on the state's faults that could increase the risk of an earthquake.

Gradual depletion of the Central Valley aquifer, because of groundwater pumping, also raises these mountain ranges by a similar amount each year--about the thickness of a dime--with a cumulative rise over the past 150 years of up to 15 centimeters (6 inches), according to calculations by a team of geophysicists.

The ...

Nanowire bridging transistors open way to next-generation electronics

2014-05-14

VIDEO:

UC Davis engineer Saif Islam explains how growing semiconductor nano-sized wires and bridges on silicon can lead to a new generation of robust electronic devices.

Click here for more information.

A new approach to integrated circuits, combining atoms of semiconductor materials into nanowires and structures on top of silicon surfaces, shows promise for a new generation of fast, robust electronic and photonic devices. Engineers at the University of California, Davis, have ...

Societies publish recommendations to guide minimally invasive valve therapy programs for patients

2014-05-14

WASHINGTON, D.C., BEVERLY, MA, and CHICAGO (May 15, 2014) – As minimally invasive therapies are increasingly used to treat diseased heart valves, newly published recommendations provide guidance on best practices for providing optimal care for patients. The document released today offers first-time guidance from four professional medical associations on developing and maintaining a transcatheter mitral valve therapy program, emphasizing collaboration between interventional cardiologists and cardiac surgeons. The document is an important step toward achieving consistent, ...

Inhibiting protein family helps mice survive radiation exposure, Stanford study finds

2014-05-14

STANFORD, Calif. - Tinkering with a molecular pathway that governs how intestinal cells respond to stress can help mice survive a normally fatal dose of abdominal radiation, according to a new study by researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine.

Because the technique is still partially effective up to 24 hours after exposure, the study suggests a possible treatment for people unintentionally exposed to large amounts of radiation, such as first responders at the Chernobyl nuclear disaster in 1986.

"We were very surprised by the amount of protection the ...

Antidepressant may slow Alzheimer's disease

2014-05-14

A commonly prescribed antidepressant can reduce production of the main ingredient in Alzheimer's brain plaques, according to new research at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and the University of Pennsylvania.

The findings, in mice and people, are published May 14 in Science Translational Medicine. They support preliminary mouse studies that evaluated a variety of antidepressants.

Brain plaques are tied closely to memory problems and other cognitive impairments caused by Alzheimer's disease. Stopping plaque buildup may halt the disastrous mental ...

Can anti-depressants help prevent Alzheimer's disease?

2014-05-14

PHILADELPHIA – A University of Pennsylvania researcher has discovered that the common selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) citalopram arrested the growth of amyloid beta, a peptide in the brain that clusters in plaques that are thought to trigger the development of Alzheimer's disease (AD). Penn, in collaboration with investigators at Washington University, tested the drug's effects on the brain interstitial fluid (ISF) in plaque-bearing mice and the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of healthy human subjects to draw its conclusions, which are detailed in the new issue ...

Hitting a moving target

2014-05-14

LA JOLLA, CA—May 14, 2014—A vaccine or other therapy directed at a single site on a surface protein of HIV could in principle neutralize nearly all strains of the virus—thanks to the diversity of targets the site presents to the human immune system.

The finding, from a study led by scientists at The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI), is likely to influence future designs for HIV vaccines and antibody-based therapies.

"We found, for example, that if the virus tries to escape from an antibody directed at that site by eliminating one of its sugars, the antibody often ...

Deformable mirror corrects errors

2014-05-14

This news release is available in German.

Lasers are used in manufacturing to cut materials or weld components together. Laser light is focused to a point using various lenses and mirrors; the smaller the focal point and the higher the energy, the more accurately operators can work with the laser. So, turn up the power and off you go, right? It is not that simple because when laser power increases, the mirror heats up accordingly, causing it to deform. A deformed mirror cannot effectively focus the laser; the focal point gets bigger and laser power falls away.

Precisely ...