(Press-News.org) An international study, led by the University of Southampton, has led to the creation of the world's first global database of jellyfish records to map jellyfish populations in the oceans.

Scientific and media debate regarding future trends, and subsequent ecological, biogeochemical and societal impacts, of jellyfish and jellyfish blooms in a changing ocean is hampered by a lack of information about jellyfish biomass and distribution from which to compare.

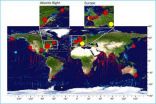

To address this knowledge gap, scientists used the Jellyfish Database Initiative, or JeDI, to map jellyfish biomass in the upper 200m of the world's oceans and explore the underlying environmental causes driving the observed patterns of distribution.

"The successful development of this first global-scale database of jellyfish records by the Global Jellyfish Group was due, in large part, to the incredible generosity of members in the international jellyfish research and wider scientific communities," says lead author of the study Dr Cathy Lucas, a marine biologist from the University of Southampton.

"With this resource, anyone can use JeDI to address questions about the spatial and temporal extent of jellyfish populations at local, regional and global scales, and the potential implications for ecosystem services and biogeochemical processes," adds Dr Rob Condon of the University of North Carolina Wilmington in the USA.

Using data from JeDI, the authors were able to show that jellyfish and other gelatinous zooplankton are present throughout the world's oceans, with the greatest concentrations in the mid-latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere. In the North Atlantic Ocean, dissolved oxygen and sea surface temperature were found to be the principal drivers of jellyfish biomass distribution.

The spatial analysis carried out by the researchers is an essential first step in the establishment of a consistent database of gelatinous presence from which future trends can be assessed and hypotheses tested, particularly those relating multiple regional and global drivers of jellyfish biomass. It complements the findings of a 2013 study, led by Dr Condon, in which global jellyfish populations were shown to exhibit fluctuations over multidecadal time-scales centred round a baseline. "If jellyfish biomass does increase in the future, particularly in the Northern Hemisphere, this may influence the abundance and biodiversity of zooplankton and phytoplankton, having a knock-on effect on ecosystem functioning, biogeochemical cycling and fish biomass," says Dr Condon.

INFORMATION:

The Jellyfish Database Initiative, or JeDI, is the first scientifically-coordinated global-scale database of jellyfish records, and currently holds over 476,000 data items on jellyfish and other gelatinous taxa. JeDI has been designed as an open-access database for all researchers, media and public to use as a current and future research tool and a data hub for general information on jellyfish populations. It is housed at the National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis (NCEAS) USA, a cross-discipline ecological and data synthesis research centre affiliated with the University of California, Santa Barbara, and can be accessed and searched at http://jedi.nceas.ucsb.edu.

The continued development of JeDI and a re-analysis several decades from now will enable science to determine whether jellyfish biomass and distribution alter as a result of anthropogenic climate change.

The results of the study, led by Dr Lucas, appear in the latest issue of Global Ecology and Biogeography (DOI: 10.1111/geb.1269). Her co-authors include Dr Daniel Jones of the National Oceanography Centre, UK and members of the Global Jellyfish Group, a consortium of approximately 30 researchers from around the globe with specialisms in gelatinous organisms, climatology, oceanography and times-series analyses, and including lead co-authors Dr Rob Condon of the University of North Carolina, Wilmington in the USA, Professor Carlos Duarte of the University of Western Australia's Oceans Institute and the Instituto Mediterráneo de Estudios Avanzadoes (IMEDEA) in Spain and Dr Kylie Pitt of Griffith University in Australia.

Marine scientists use JeDI to create world's first global jellyfish database

2014-05-15

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Study: Addressing 'mischievous responders' would increase validity of adolescent research

2014-05-15

WASHINGTON, D.C., May 15, 2014 ─ "Mischievous responders" play the game of intentionally providing inaccurate answers on anonymous surveys, a widespread problem that can mislead research findings. However, new data analysis procedures may help minimize the impact of these "jokester youths," according to research published online today in Educational Researcher, a peer-reviewed journal of the American Educational Research Association (AERA).

VIDEO: Author Joseph P. Robinson-Cimpian discusses key findings: http://youtu.be/WFFaA74sygI.

"Inaccurate Estimation of ...

Neural pathway to parenthood

2014-05-15

Good news for Dads: Harvard researchers say the key to being a better parent is – literally – all in your head.

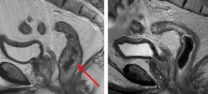

In a study in mice, Higgins Professor of Molecular and Cellular Biology and Howard Hughes Investigator Catherine Dulac have pinpointed galanin neurons in the brain's medial preoptic area (MPOA), that appear to regulate parental behavior. If similar neurons are at work in humans, it could offer clues to the treatment of conditions like post-partum depression. The study is described in a May 15 paper published in Nature.

"If you look across different animal ...

Getting chemo first may help in rectal cancer

2014-05-15

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — First things first. If cancer patients are having trouble tolerating chemotherapy after chemoradiation and surgery, then try administering it beforehand. Reordering the regimen that way enabled all but six of 39 patients to undergo a full course of standard treatment for rectal cancer, according to research to be presented at the American Society for Clinical Oncology annual meeting in Chicago.

Studies have shown that only about 60 percent of rectal cancer patients comply with postoperative chemotherapy, said lead researcher Dr. Kimberly ...

MIPT experts reveal the secret of radiation vulnerability

2014-05-15

The scientists - Boris Kuzin, Ekaterina Nikitina, Roman Cherezov, Julia Vorontsova, Mikhail Slezinger, Olga Zatsepina, Olga Simonova, Grigori Enikolopov and Elena Savvateeva-Popova - studied Drosophila flies, in whose genome weak mutations of two different genes were combined. The paper is published in the PLoS One. They concluded that these mutations synergistically strengthen their mutual phenotypic expression. In other words, the aggregate effect of these mutations is much greater than that which can be produced by one of them individually.

The mutant flies bred by ...

MIPT scientists develop algorithm for anti-aging remedy search

2014-05-15

The scientists – Alexander Zhavoronkov, Anton Buzdin, Andrey Garazha, Nickolay Borisov and Alexey Moskalev– have based the new research on their previously-developed methods in the study of cancer cells. Each cell uses particular schemes of molecular interaction, which physiologists call intercellular signaling pathways.

A signaling pathway is a chain of sequential events of interaction between certain molecules which make the cell respond to stimulation. For example, hormone molecules first interact with the cell's membrane receptors, then the receptors engage with the ...

Next frontier: How can modern medicine help dying patients achieve a 'good' death?

2014-05-15

(TORONTO, Canada – May, 15, 2014) -- The overall quality of death of cancer patients who die in an urban Canadian setting with ready access to palliative care was found to be good to excellent in the large majority of cases, helping to dispel the myth that marked suffering at the end of life is inevitable.

"Fear of dying is something almost every patient with advanced cancer or other life-threatening illness faces, and helping them, to achieve a "good death" is an important goal of palliative care," says Dr. Sarah Hales, Coordinator of Psychiatry Services, Psychosocial ...

Study shows young men increasingly outnumber young women in rural Great Plains

2014-05-15

Lincoln, Neb., May 15, 2014 -- In many rural communities hard hit by decades of population declines, young men increasingly outnumber young women, a new study of Kansas and Nebraska census data shows.

In places with 800 or fewer residents, the proportion of young men increased by an average of nearly 40 percent as people went from their teens to their 20s.

Those findings suggest leaders should consider the needs of young women in their economic and community development plans, said Robert Shepard, a University of Nebraska-Lincoln doctoral candidate ...

Most NHL players peak by age 29: Study

2014-05-15

A new University of British Columbia study identifies when the clock runs out on an NHL player's peak performance, giving team executives insight into how best to build a roster.

The study by Sauder School of Business professor James Brander found that the performance of forwards peaks between the ages of 27 and 28. Defencemen are best between 28 and 29, and the performance of goaltenders varies little by age.

The forthcoming study to be published in the Journal of Quantitative Analysis in Sports also reveals that players performed close to their peak levels for a ...

Learning from sharks

2014-05-15

This news release is available in German.

Custom-tailored antibodies are regarded as promising weapons against a multitude of serious illnesses. Since they can accurately recognize specific structures on the surface of viruses, bacteria or cancer cells, they are already being deployed successfully in cancer diagnostics and therapy, as well as against numerous other diseases. The stability of the sensitive antibodies is a decisive factor in every step, from production and storage to therapeutic application.

A team of researchers headed by Dr. Matthias J. Feige and ...

Where have all the mitochondria gone?

2014-05-15

It's common knowledge that all organisms inherit their mitochondria – the cell's "power plants" – from their mothers. But what happens to all the father's mitochondria? Surprisingly, how – and why – paternal mitochondria are prevented from getting passed on to their offspring after fertilization is still shrouded in mystery; the only thing that's certain is that there must be a compelling reason, seeing as this phenomenon has been conserved throughout evolution.

Now, Dr. Eli Arama and a team in the Weizmann Institute's Molecular Genetics Department have discovered special ...