(Press-News.org) The body's innate immune system is a first line of defense, intent on sensing invading pathogens and wiping them out before they can cause harm. It should not be surprising then that bacteria have evolved many ways to specifically evade and overcome this sentry system in order to spread infection.

A study led by researchers in the University of Pennsylvania's School of Veterinary Medicine now reveals how some Salmonella bacteria hide from the immune system, allowing them to persist and cause systemic infection. The findings could help researchers craft a more effective vaccine against Salmonella.

Igor Brodsky, an assistant professor in Penn Vet's Department of Pathobiology, was senior author on the paper, which was published in the Journal of Experimental Medicine. Co-authors included Penn Vet postdoctoral associates Meghan A. Wynosky-Dolfi and Patrick J. Doonan, Ph.D. students Naomi H. Philip, Erin E. Zwack and Amber M. Riblett and department colleague Bruce D. Freedman. The Penn researchers collaborated with Till Strowig and Richard A. Flavell of Yale University School of Medicine and Maya C. Poffenberger, Daina Avizonis and Russell G. Jones of McGill University.

"Many of the same signals that are present in harmless bacteria are also present in pathogenic bacteria," Brodsky said. "One of the big unanswered questions is how does the innate immune system distinguish between the two? And, conversely, how have pathogenic bacteria evolved to get around the immune response?"

The Penn study addresses both questions, focusing on a component of the innate immune response called the inflammasome. Consisting of a complex of proteins that triggers the release of signaling molecules, the inflammasome serves to recruit other components of the immune system that can fight off the pathogen.

"We hypothesized that during the systemic phase of disease, Salmonella would have some way of avoiding inflammasome activation," Brodsky said.

To identify the mechanism by which the bacteria might do this, Brodsky's team made a library of Salmonella mutants, looking for those that might be involved in the evasion strategy.

Among the 18 genes they pinpointed were four that had been previously noted to have a role in enabling Salmonella strains to cause long-term, chronic infections.

"That was interesting because it suggested that at least a subset of those genes that might be important for long-term infection might be involved in evading or suppressing the inflammasome response," Brodsky said.

They trained their attention on one of these four, the gene that encodes the enzyme aconitase. Aconitase, which converts citrate to isocitrate, is a key component in the metabolic process known as the citric acid or Krebs cycle. This cycle is used by all oxygen-breathing organisms to convert sugar into energy and to produce important molecules for cell growth.

When the aconitase gene was mutated, the inflammasome known as NLRP3 was highly activated, leading researchers to believe that the normal version of aconitase might do the opposite, inhibiting the inflammasome. Moreover, when the researchers infected mice with a strain of Salmonella that had a mutated version of aconitase, the rodents were able to clear the infection, likely due to the inflammasome being activated. This infection led to increased levels of inflammation in the mice's tissues.

The Penn-led team also wanted to see whether other components of the citric acid cycle might be involved in inflammasome activation. They found that mutating Salmonella genes that encode two other players in the cycle, the enzymes isocitrate dehydrogenase and isocitrate lyase, also led to higher activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome.

In their normal state, these enzymes break down citrate. Thus the study's results point to the possibility that the immune system may activate the inflammasome in response to the presence of citrate or some byproduct of citrate. Supporting this idea, the researchers found that Salmonella strains lacking the enzyme citrate synthase, which produces citrate, led to a reduced inflammatory response.

"We think bacteria might be exporting citrate because it would otherwise prevent the bacteria from growing," Brodsky said. "It's possible that the export of citrate might be triggering the inflammatory response. Our work fits into this emerging idea that bacterial metabolites might be recognized by various components of the immune system for the purpose of either negatively or positively regulating immune responses."

The scientists believe that it's possible that host cells put together two pieces of information to trigger an immune response, first recognizing signaling of a Toll-like receptor, which responds to structures that are common across many microbes, and then sensing bacterial products, like elevated levels of citrate, being produced inside the cell itself.

Brodsky and colleagues are now working to develop a chicken vaccine based on an attenuated strain of Salmonella that would trigger both "arms" of the inflammatory response, possibly involving an aconitase mutant. Such a vaccine would ideally more closely replicate a natural infection, protecting the animals against infection.

"We get Salmonella from chickens that are chronically infected," Brodsky said, "so, if you could prevent or limit chronic infection of chickens, that would be a nice way to limit Salmonella in the food supply."

INFORMATION:

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, Penn's University Research Foundation, the McCabe Fund, the Center for Molecular Studies in Digestive and Liver Diseases and Penn Vet's Mari-Lowe Center for Comparative Oncology.

Penn Vet study reveals Salmonella's hideout strategy

2014-05-15

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Research finds human impact may cause Sierra Nevada to rise, increase seismicity of San Andreas Fault

2014-05-15

RENO, Nev. – Like a detective story with twists and turns in the plot, scientists at the University of Nevada, Reno are unfolding a story about the rapid uplift of the famous 400-mile long Sierra Nevada mountain range of California and Nevada.

The newest chapter of the research is being published today in the scientific journal Nature, showing that draining of the aquifer for agricultural irrigation in California's Central Valley results in upward flexing of the earth's surface and the surrounding mountains due to the loss of mass within the valley. The groundwater subsidence ...

A skeleton clue to early American ancestry

2014-05-15

This news release is available in Spanish and Arabic.

The discovery of a near-complete human skeleton in a watery cave in Mexico is helping scientists answer the question, "Who were the first Americans?" The finding, reported in the 16 May issue of the journal Science, sheds new light on a decades-long debate among archaeologists and anthropologists.

Deciphering the ancestry of the first people to populate the Americas has been a challenge.

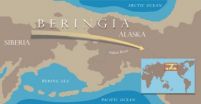

On the basis of genetics, modern Native Americans are thought to descend from Siberians who moved into eastern Beringia (the ...

Oldest most complete, genetically intact human skeleton in New World

2014-05-15

WASHINGTON (May 15, 2014)—The skeletal remains of a teenage female from the late Pleistocene or last ice age found in an underwater cave in Mexico have major implications for our understanding of the origins of the Western Hemisphere's first people and their relationship to contemporary Native Americans.

In a paper released today in the journal Science, an international team of researchers and cave divers present the results of an expedition that discovered a near-complete early American human skeleton with an intact cranium and preserved DNA. The remains were found surrounded ...

WSU anthropologist leads genetic study of prehistoric girl

2014-05-15

PULLMAN, Wash.—For more than a decade, Washington State University molecular anthropologist Brian Kemp has teased out the ancient DNA of goose and salmon bones from Alaska, human remains from North and South America, and human coprolites—ancient poop—from Oregon and the American Southwest.

His aim: use genetics as yet another archaeological record offering clues to the identities of ancient people and how they lived and moved across the landscape.

As head of the team studying the DNA of Naia, an adolescent girl who fell into a Yucatan sinkhole some 12,000 years ago, he ...

Genetic study helps resolve years of speculation about first people in the Americas

2014-05-15

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — A new study could help resolve a longstanding debate about the origins of the first people to inhabit the Americas, researchers report in the journal Science. The study relies on genetic information extracted from the tooth of an adolescent girl who fell into a sinkhole in the Yucatan 12,000 to 13,000 years ago.

The girl's remains were found alongside those of ancient extinct beasts that also fell into the "inescapable natural trap," as researchers described the sinkhole. The team used radiocarbon dating and analyzed chemical signatures in bones and ...

Dating and DNA show Paleoamerican-Native American connection

2014-05-15

Eastern Asia, Western Asia, Japan, Beringia and even Europe have all been suggested origination points for the earliest humans to enter the Americas because of apparent differences in cranial form between today's Native Americans and the earliest known Paleoamerican skeletons. Now an international team of researchers has identified a nearly complete Paleoamerican skeleton with Native American DNA that dates close to the time that people first entered the New World.

"Individuals from 9,000 or more years ago have morphological attributes -- physical form and structure -- ...

Genetic study confirms link between earliest Americans and modern Native-Americans

2014-05-15

AUSTIN, Texas — The ancient remains of a teenage girl found in an underwater Mexican cave establish a definitive link between the earliest Americans and modern Native Americans, according to a new study released today in the journal Science.

The study was conducted by an international team of researchers from 13 institutions, including Deborah Bolnick, assistant professor of anthropology at The University of Texas at Austin, who analyzed DNA from the remains simultaneously with independent researchers at Washington State University and the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

The ...

First 'heavy mouse' leads to first lab-grown tissue mapped from atomic life

2014-05-15

Scientists have created a 'heavy' mouse, the world's first animal enriched with heavy but non-radioactive isotopes - enabling them to capture in unprecedented detail the molecular structure of natural tissue by reading the magnetism inherent in the isotopes.

This data has been used to grow biological tissue in the lab practically identical to native tissue, which can be manipulated and analysed in ways impossible for natural samples. Researchers say the approach has huge potential for scientific and medical breakthroughs: lab-grown tissue could be used to replace heart ...

One of oldest human skeletons in North America is discovered

2014-05-15

Cave-diving scientist Patricia A. Beddows of Northwestern University is a member of an international team of researchers and cave divers this week announcing the discovery in an underwater Yucatán Peninsula cave of one of the oldest human skeletons found in North America.

Details of "Naia," a teenage girl who went underground to seek water and fell to her death in a large pit named Hoyo Negro ("black hole" in Spanish), will be published May 16 in the journal Science.

"The preservation of all the bones in this deep water-filled cave is amazing -- the bones are beautifully ...

Communicating with the world across the border

2014-05-15

Stanford, CA—All living cells are held together by membranes, which provide a barrier to the transport of nutrients. They are also the communication platform connecting the outside world to the cell’s interior control centers. Thousands of proteins reside in these cell membranes and control the flow of select chemicals, which move across the barrier and mediate the flux of nutrients and information. Almost all of these pathways work by protein handshakes--one protein “talking” to another in order to, for example, encourage the import of a needed nutrient, to block a compound ...