(Press-News.org) PITTSBURGH, May 16, 2014 – The first direct proof of a long-suspected cause of multiple HIV-related health complications was recently obtained by a team led by the University of Pittsburgh Center for Vaccine Research (CVR). The finding supports complementary therapies to antiretroviral drugs to significantly slow HIV progression.

The study, which will be published in the June issue of the Journal of Clinical Investigation and is available online, found that a drug commonly given to patients receiving kidney dialysis significantly diminishes the levels of bacteria that escape from the gut and reduces health complications in non-human primates infected with the simian form of HIV. The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

"We now have direct evidence of a major culprit in poor outcomes for some HIV-infected people, which is an important breakthrough in the fight against AIDS," said Ivona Pandrea, M.D., Ph.D., professor of pathology at Pitt's CVR. "Researchers and doctors can now better test potential therapies to slow or stop a key cause of death and heart disease in people with HIV."

Chronic activation of the immune system and inflammation are major determinants of progression of HIV infection to AIDS, and also play an important role in inducing excessive blood clotting and heart disease in HIV patients. Doctors believed this was due to microbial translocation, which occurs when bacteria in the gut gets out into the body through intestinal lining damaged by HIV. However, no direct proof of this mechanism existed.

Dr. Pandrea and her colleagues showed blocking the bacteria from leaving the intestine reduces the chronic immune activation and inflammation. They did this by giving the drug Sevelamer, also known by the brand names Renvela and Renagel, to monkeys newly infected with simian immunodeficiency virus, or SIV, the primate-form of HIV.

Sevelamer is an oral drug approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat elevated levels of phosphate in the blood of patients with chronic kidney disease.

The gut bacteria bind to Sevelamer, making it much more difficult for the bacteria to escape into the body and cause serious problems, such as heart disease, while further weakening the immune system and allowing HIV to progress to full-blown AIDS.

In SIV-infected monkeys treated with Sevelamer, levels of a protein that indicates microbial translocation remained low. However, in the untreated monkeys the levels increased nearly four-fold a week after SIV infection.

The treated monkeys with the lower rates of microbial translocation also had lower levels of a biomarker associated with excessive blood clotting, showing that heart attacks and stroke in HIV patients are more likely associated with chronic immune system activation and inflammation, rather than HIV drugs.

"These findings clearly demonstrate that stopping bacteria from leaving the gut reduces the rates of many HIV comorbidities," said Dr. Pandrea.

Because most interventions in people infected with HIV begin after the person has reached chronic stages of infection when the gut is already severely damaged, Dr. Pandrea notes, "These treatments may not be as effective later in the infection. Clinical trials in HIV-infected patients were not yet successful in reducing microbial translocation in chronically infected patients. Our study points to the importance of early and sustained drug treatment in people infected with HIV."

Other approaches, such as coupling Sevelamer with antibiotics, anti-inflammatory drugs, probiotics or supplementation of existing HIV/AIDS drugs could further reduce the likelihood of microbial translocation. Clinical trials are underway to assess these strategies.

INFORMATION:

Additional researchers on this study are Jan Kristoff, B.A., M.S., George Haret-Richter, Ph.D., Dongzhu Ma, Ph.D., Cuiling Xu, Ph.D., Jennifer L. Stock, B.S., Tianyu He, B.S., Adam D. Mobley, B.S., Samantha Ross, B.A., M.S., Anita Trichel, D.V.M., Ph.D., Cristian Apetrei, M.D. Ph.D., all of Pitt; Alan Landay, Ph.D., Rush University; Ruy M. Ribeiro, Ph.D., Los Alamos National Laboratory; Elaine Cornell, technician, and Russell Tracy, Ph.D., both of the University of Vermont; and Cara Wilson, M.D., of the University of Colorado.

This work was supported by NIH grants R01 HL117715, R01 RR025781, 5P01 AI076174 and P30 AI082151.

About the University of Pittsburgh Schools of the Health Sciences

The University of Pittsburgh Schools of the Health Sciences include the schools of Medicine, Nursing, Dental Medicine, Pharmacy, Health and Rehabilitation Sciences and the Graduate School of Public Health. The schools serve as the academic partner to the UPMC (University of Pittsburgh Medical Center). Together, their combined mission is to train tomorrow's health care specialists and biomedical scientists, engage in groundbreaking research that will advance understanding of the causes and treatments of disease and participate in the delivery of outstanding patient care. Since 1998, Pitt and its affiliated university faculty have ranked among the top 10 educational institutions in grant support from the National Institutes of Health. For additional information about the Schools of the Health Sciences, please visit http://www.health.pitt.edu.

http://www.upmc.com/media

Contact: Allison Hydzik

Phone: 412-647-9975

E-mail: HydzikAM@upmc.edu

Contact: Wendy Zellner

Phone: 412-586-9771

E-mail: ZellnerWL@upmc.edu END

Breakthrough in HIV/AIDS research gives hope for improved drug therapy

2014-05-17

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Transgenic mice produce both omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids on carbohydrate diet

2014-05-17

Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) investigators have developed a transgenic mouse that synthesizes both the omega-3 and omega-6 essential fatty acids within its tissues on a diet of carbohydrates or saturated fats. Called "essential" because they are necessary to maintain important bodily functions, omega fatty acids cannot naturally be synthesized by mammals and therefore must be acquired by diet. Significant evidence suggest that the ratio of dietary omega-6 to omega-3 has important implications for human health, further increasing interest in the development of ...

Gender differences stand out in measuring impact of Viagra as therapy for heart failure

2014-05-17

New animal studies by Johns Hopkins cardiovascular researchers strongly suggest that sildenafil, the erectile dysfunction drug sold as Viagra and now under consideration as a treatment for heart failure, affects males and females very differently.

The results of their investigations in varied male and female mouse models of heart failure are so clear-cut, says lead scientist Eiki Takimoto, M.D., Ph.D., that physicians may need to take gender into consideration when prescribing certain medications and that drug developers would be wise to take them into careful account ...

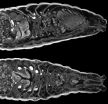

The early earthworm catches on to full data release

2014-05-17

To quote the American cartoonist Gary Larson: all things play a role in nature, even the lowly worm—but perhaps never in such a visually stunning way as that presented in two papers published today in the open access journals GigaScience and PLOS ONE. The work and data presented here provide the first-ever comparative study of earthworm morphology and anatomy using a 3D non-invasive imaging technique called micro-computed tomography (or microCT), which digitizes worm structures. This opens the possibility of scanning millions of specimens from museum collections, including ...

JCI online ahead of print table of contents for May 16, 2014

2014-05-16

Targeting microbial translocation attenuates SIV-mediated inflammation

Patients with HIV often present with signs of immune activation and systemic inflammation, both of which are hypothesized to directly contribute to the development of AIDs in infected individuals. HIV and the related simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) damage the gut mucosa, leading to translocation of microbes from the intestinal lumen to the general circulation, but it is not clear if microbial translocation is directly responsible for chronic HIV-associated inflammation. In this issue of the Journal ...

Methadone programs can be key in educating, treating HCV patients

2014-05-16

BUFFALO, N.Y. – People who inject drugs and are enrolled in a drug treatment program are receptive to education about, and treatment for, hepatitis C virus, according to a study by researchers at several institutions, including the University at Buffalo.

That finding, published online this week in the Journal of Addiction Medicine will be welcome news to health care providers. The paper notes that injection drug use is a primary mode of infection, making for an HCV infection prevalence as high as 80 percent among people who inject drugs.

"One of the most important findings ...

Non-invasive lithotripsy leads to more treatment for kidney stones

2014-05-16

DURHAM, N.C. – When it comes to treating kidney stones, less invasive may not always be better, according to new research from Duke Medicine.

In a direct comparison of shock wave lithotripsy vs. ureteroscopy – the two predominant methods of removing kidney stones – researchers found that ureteroscopy resulted in fewer repeat treatments.

The findings were published May 16, 2014, in the journal JAMA Surgery, coinciding with presentation at the annual meeting of the American Urological Association.

"Nearly one out of 11 people in the United States has kidney stones, ...

Cognitive behavioral or relaxation training helps women reduce distress during breast cancer treatment

2014-05-16

Coral Gables, Fla. (May 16, 2014) – Can psychological intervention help women adapt to the stresses of breast cancer? It appears that a brief, five-week psychological intervention can have beneficial effects for women who are dealing with the stresses of breast cancer diagnosis and surgery. Intervening during this early period after surgery may reduce women's distress and providing cognitive or relaxation skills for stress management to help them adapt to treatment.

Researchers at the University of Miami recruited 183 breast cancer patients from surgical oncology clinics ...

Spiders spin possible solution to 'sticky' problems

2014-05-16

Researchers at The University of Akron are again spinning inspiration from spider silk—this time to create more efficient and stronger commercial and biomedical adhesives that could, for example, potentially attach tendons to bones or bind fractures.

The Akron scientists created synthetic duplicates of the super-sticky, silk "attachment discs" that spiders use to attach their webs to surfaces. These discs are created when spiders pin down an underlying thread of silk with additional threads, like stiches or staples, explains Ali Dhinojwala, UA's H. A. Morton professor ...

With imprecise chips to the artificial brain

2014-05-16

This news release is available in German. Which circuits and chips are suitable for building artificial brains using the least possible amount of power? This is the question that Junior Professor Dr. Elisabetta Chicca from the Center of Excellence Cognitive Interaction Technology (CITEC) has been investigating in collaboration with colleagues from Italy and Switzerland.

Their surprising finding: Constructions that use not only digital but also analog compact and imprecise circuits are more suitable for building artificial nervous systems, rather than arrangements ...

Lighting the way to graphene-based devices

2014-05-16

Graphene continues to reign as the next potential superstar material for the electronics industry, a slimmer, stronger and much faster electron conductor than silicon. With no natural energy band-gap, however, graphene's superfast conductance can't be switched off, a serious drawback for transistors and other electronic devices. Various techniques have been deployed to overcome this problem with one of the most promising being the integration of ultrathin layers of graphene and boron nitride into two-dimensional heterostructures. As conductors, these bilayered hybrids ...