(Press-News.org) An octopus's arms are covered in hundreds of suckers that will stick to just about anything, with one important exception: those suckers generally won't grab onto the octopus itself, otherwise the impressively flexible animals would quickly find themselves all tangled up.

Now, researchers from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem report that they discovered how octopuses manage this feat, even as the creatures' brains are unaware of what their arms are doing. A chemical produced by octopus skin temporarily prevents their suckers from sucking.

"We were surprised that nobody before us had noticed this very robust and easy-to-detect phenomenon," says Dr. Guy Levy, who carried out the research with co-first author Dr. Nir Nesher in the Department of Neurobiology at the Hebrew University's Alexander Silberman Institute of Life Sciences. "We were entirely surprised by the brilliant and simple solution of the octopus to this potentially very complicated problem."

Prof. Binyamin (Benny) Hochner, Principal Investigator in the Hebrew University's Octopus Research Group, and his colleagues had been working with octopuses for many years, focusing especially on their flexible arms and body motor control. Prof. Hochner is a researcher at the Department of Neurobiology at the Alexander Silberman Institute of Life Sciences and the Interdisciplinary Center for Neural Computation at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Hochner explains there is a good reason that octopuses don't know where their arms are the same way that people or other animals do. "Our motor control system is based on a rather fixed representation of the motor and sensory systems in the brain in a formant of maps that have body part coordinates." That works for us because our rigid skeletons limit the number of possibilities.

"It is hard to envisage similar mechanisms to function in the octopus brain because its very long and flexible arms have an infinite number of degrees of freedom," Hochner adds. "Therefore, using such maps would have been tremendously difficult for the octopus, and maybe even impossible."

Indeed, experiments have supported the notion that octopuses lack accurate knowledge about the position of their arms. And that raised an intriguing question: How do octopuses avoid tying themselves up in knots?

To answer that question, the researchers observed that octopus arms remain active for an hour after amputation. Those observations showed that the arms never grabbed octopus skin, though they would grab a skinned octopus arm. The octopus arms didn't grab Petri dishes covered with octopus skin, either, and they attached to dishes covered with octopus skin extract with much less force than they otherwise would.

"The results so far show, and for the first time, that the skin of the octopus prevents octopus arms from attaching to each other or to themselves in a reflexive manner," the researchers write. "The drastic reduction in the response to the skin crude extract suggests that a specific chemical signal in the skin mediates the inhibition of sucker grabbing."

In contrast to the behavior of the amputated arms, live octopuses can override that automatic mechanism when it is convenient. Living octopuses will sometimes grab an amputated arm, and they appear to be more likely to do so when that arm was not formerly their own.

Hochner and his colleagues haven't yet identified the active agent in the animals' self-avoidance behavior, but they say it is yet another demonstration of octopus intelligence. The self-avoidance strategy might even find its way into bio-inspired robot design.

"Soft robots have advantages [in] that they can reshape their body," Nesher says. "This is especially advantageous in unfamiliar environments with many obstacles that can be bypassed only by flexible manipulators, such as the internal human body environment."

The researchers are sharing their findings with European Commission project STIFF-FLOP, which aims to develop a flexible surgical manipulator in the shape of an octopus arm. "We hope and believe that this mechanism will find expression in such new classes of robots and their control systems," Hochner says.

INFORMATION:

The research, "Self-recognition mechanism between skin and suckers prevents octopus arms from interfering with each other," was published in the Cell Press publication Current Biology on May 15. It was co-authored by Nesher, Levy, Hochner and Prof. Frank. W. Grasso at the BioMimetic and Cognitive Robotics Laboratory, Brooklyn College, The City University of New York.

The research was supported by the European Commission EP-7 projects STIFF-FLOP and OCTOPUS.

How octopuses don't tie themselves in knots revealed by Hebrew University scientists

Research may help advance bio-inspired robot design

2014-05-19

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

The spot-tail golden bass: A new fish species from deep reefs of the southern Caribbean

2014-05-19

Smithsonian scientists describe a colorful new species of small coral reef sea bass from depths of 182–241 m off Curaçao, southern Caribbean. With predominantly yellow body and fins, the new species, Liopropoma santi, closely resembles the other two "golden basses" found together with it at Curaçao: L. aberrans and L. olneyi.

The scientists originally thought there was a single species of golden bass on deep reefs off Curaçao, but DNA data, distinct color patterns, and morphology revealed three. The study describing one of those, L. santi—the deepest known species of ...

Neutron beams reveal how antibodies cluster in solution

2014-05-19

Scientists have used small-angle neutron scattering (SANS) and neutron spin-echo (NSE) techniques for the first time to understand how monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), a class of targeted biopharmaceuticals used to treat autoimmune disorders and cancer, dynamically cluster and move in high concentration solutions. Certain mAb cluster arrangements can thicken pharmaceutical solutions; they could thus limit the feasible concentration of injectables administered to patients around the world. The insights provided by a team of neutron scientists from the National Center of Neutron ...

San Diego county fires still rage

2014-05-19

The San Diego County fires that began on Wednesday May 14 as a single fire that erupted into nine fires that burned out of control for days. According to News Channel 8, the ABC affiliate in San Diego, the following summarizes what the current conditions are for the fires still left burning:

"Cocos Fire - San Marcos: This fire has burned 1,995 acres and is 87 percent contained Monday morning. All evacuation orders and road closures were lifted as of 11 a.m. Sunday, according to the City of San Marcos.

San Mateo Fire - Camp Pendleton: The San Mateo Fire that was reported ...

New technique to prevent anal sphincter lesions due to episiotomy during child delivery

2014-05-19

Results of a 10-year long multinational research project on Technologies for Anal Sphincter analysis and Incontinence (TASI) are available in:

Corrado Cescon, Diego Riva , Vita Začesta, Kristina Drusany-Starič, Konstantinos Martsidis,

Olexander Protsepko, Kaven Baessler, Roberto Merletti

Effect of vaginal delivery on the external anal sphincter muscle innervation pattern evaluated by multichannel surface EMG: results of the multicentre study TASI-2

International Urogynecology Journal, DOI 10.1007/s00192-014-2375-0.

Episiotomy is a controversial surgical ...

Studies published in NEJM identify promising drug therapies for fatal lung disease

2014-05-19

LOS ANGELES (May 18, 2014) – Researchers in separate clinical trials found two drugs slow the progression of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, a fatal lung disease with no effective treatment or cure, and for which there is currently no therapy approved by the Food and Drug Administration.

Paul W. Noble, MD, chair of the Department of Medicine at Cedars-Sinai and director of the Women's Guild Lung Institute, is the senior author of the multicenter study that found that the investigational drug pirfenidone significantly slowed the loss of lung function and reduced the ...

EPA ToxCast data validates BioMAP® systems' ability to predict drug, chemical toxicities

2014-05-19

FREMONT, CA (May 19, 2014): Newly published research demonstrates the ability of BioMAP® Systems, a unique set of primary human cell and co-culture assays that model human disease and pathway biology, to identify important safety aspects of drugs and chemicals more efficiently and accurately than can be achieved by animal testing. Data from BioMAP Systems analysis of 776 environmental chemicals, including reference pharmaceuticals and failed drugs, on their ability to disrupt physiologically important human biological pathways were published online this week in Nature ...

Fluoridating water does not lower IQ: New Zealand research

2014-05-19

New research out of New Zealand's world-renowned Dunedin Multidisciplinary Study does not support claims that fluoridating water adversely affects children's mental development and adult IQ.

The researchers were testing the contentious claim that exposure to levels of fluoride used in community water fluoridation is toxic to the developing brain and can cause IQ deficits. Their findings are newly published in the highly respected American Journal of Public Health.

The Dunedin Study has followed nearly all aspects of the health and development of around 1000 people born ...

Chinese scientists crack the genome of another diploid cotton Gossypium arboreum

2014-05-19

Shenzhen, May 18, 2014---Chinese scientists from Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences and BGI successfully deciphered the genome sequence of another diploid cotton-- Gossypium arboreum (AA) after the completed sequencing of G. raimondii (DD) in 2012. G. arboreum, a cultivated cotton, is a putative contributor for the A subgenome of cotton. Its completed genome will play a vital contribution to the future molecular breeding and genetic improvement of cotton and its close relatives. The latest study today was published online in Nature Genetics.

As one of the most ...

The young sperm, poised for greatness

2014-05-19

SALT LAKE CITY— In the body, a skin cell will always be skin, and a heart cell will always be heart. But in the first hours of life, cells in the nascent embryo become totipotent: they have the incredible flexibility to mature into skin, heart, gut, or any type of cell.

It was long assumed that the joining of egg and sperm launched a dramatic change in how and which genes were expressed. Instead, new research shows that totipotency is a step-wise process, manifesting as early as in precursors to sperm, called adult germline stem cells (AGSCs), which reside in the testes. ...

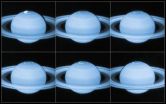

'Smoking gun' evidence for theory that Saturn's collapsing magnetic tail causes auroras

2014-05-19

University of Leicester researchers have captured stunning images of Saturn's auroras as the planet's magnetic field is battered by charged particles from the Sun.

The team's findings provide a "smoking gun" for the theory that Saturn's auroral displays are often caused by the dramatic collapse of its "magnetic tail".

Just like comets, planets such as Saturn and the Earth have a "tail" – known as the magnetotail – that is made up of electrified gas from the Sun and flows out in the planet's wake.

When a particularly strong burst of particles from the Sun hits Saturn, ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Molecular glue discovery: large scale instead of lucky strike

Insulin resistance predictor highlights cancer connection

Explaining next-generation solar cells

Slippery ions create a smoother path to blue energy

Magnetic resonance imaging opens the door to better treatments for underdiagnosed atypical Parkinsonisms

National poll finds gaps in community preparedness for teen cardiac emergencies

One strategy to block both drug-resistant bacteria and influenza: new broad-spectrum infection prevention approach validated

Survey: 3 in 4 skip physical therapy homework, stunting progress

College students who spend hours on social media are more likely to be lonely – national US study

Evidence behind intermittent fasting for weight loss fails to match hype

How AI tools like DeepSeek are transforming emotional and mental health care of Chinese youth

Study finds link between sugary drinks and anxiety in young people

Scientists show how to predict world’s deadly scorpion hotspots

ASU researchers to lead AAAS panel on water insecurity in the United States

ASU professor Anne Stone to present at AAAS Conference in Phoenix on ancient origins of modern disease

Proposals for exploring viruses and skin as the next experimental quantum frontiers share US$30,000 science award

ASU researchers showcase scalable tech solutions for older adults living alone with cognitive decline at AAAS 2026

Scientists identify smooth regional trends in fruit fly survival strategies

Antipathy toward snakes? Your parents likely talked you into that at an early age

Sylvester Cancer Tip Sheet for Feb. 2026

Online exposure to medical misinformation concentrated among older adults

Telehealth improves access to genetic services for adult survivors of childhood cancers

Outdated mortality benchmarks risk missing early signs of famine and delay recognizing mass starvation

Newly discovered bacterium converts carbon dioxide into chemicals using electricity

Flipping and reversing mini-proteins could improve disease treatment

Scientists reveal major hidden source of atmospheric nitrogen pollution in fragile lake basin

Biochar emerges as a powerful tool for soil carbon neutrality and climate mitigation

Tiny cell messengers show big promise for safer protein and gene delivery

AMS releases statement regarding the decision to rescind EPA’s 2009 Endangerment Finding

Parents’ alcohol and drug use influences their children’s consumption, research shows

[Press-News.org] How octopuses don't tie themselves in knots revealed by Hebrew University scientistsResearch may help advance bio-inspired robot design