(Press-News.org) LA JOLLA, CA – May 19, 2014 – Chemists at The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) have determined the correct structure of a highly promising anticancer compound approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for clinical trials in cancer patients.

The new report, published this week by the international chemistry journal Angewandte Chemie, focuses on a compound called TIC10.

In the new study, the TSRI scientists show that TIC10's structure differs subtly from a version published by another group last year, and that the previous structure associated with TIC10 in fact describes a molecule that lacks TIC10's anticancer activity.

By contrast, the correct structure describes a molecule with potent anticancer effects in animals, representing a new family of biologically active structures that can now be explored for their possible therapeutic uses.

"This new structure should generate much interest in the cancer research community," said Kim D. Janda, the Ely R. Callaway Jr. Professor of Chemistry and member of the Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology at TSRI.

Antitumor Potential

TIC10 was first described in a paper in the journal Science Translational Medicine in early 2013. The authors identified the compound, within a library of thousands of molecules maintained by the National Cancer Institute (NCI), for its ability to boost cells' production of a powerful natural antitumor protein, TRAIL. (TIC10 means TRAIL-Inducing Compound #10.)

As a small molecule, TIC10 would be easier to deliver in a therapy than the TRAIL protein itself. The paper, which drew widespread media coverage, reported that TIC10 was orally active and dramatically shrank a variety of tumors in mice, including notoriously treatment-resistant glioblastomas.

Tumors can develop resistance to TRAIL, but Janda had been studying compounds that defeat this resistance. The news about TIC10 therefore got his attention. "I thought, 'They have this molecule for upregulating TRAIL, and we have these molecules that can overcome tumor cell TRAIL resistance—the combination could be important,'" he said.

The original publication on TIC10 included a figure showing its predicted structure. "I saw the figure and asked one of my postdocs, Jonathan Lockner, to make some," Janda said.

Although the other team had seemingly confirmed the predicted structure with a basic technique called mass spectrometry, no one had yet published a thorough characterization of the TIC10 molecule. "There were no nuclear magnetic resonance data or X-ray crystallography data, and there was definitely no procedure for the synthesis," Lockner said. "My background was chemistry, though, so I was able to find a way to synthesize it starting from simple compounds."

Surprising Inactivity

There was just one problem with Lockner's newly synthesized "TIC10." When tested, it failed to induce TRAIL expression in cells, even at high doses.

"Of course I was nervous," remembered Lockner. "As a chemist, you never want to make a mistake and give biologists the wrong material."

To try to verify they had the right material, Janda's team obtained a sample of TIC10 directly from the NCI. "When we got that sample and tested it, we saw that it had the expected TRAIL-upregulating effect," said Nicholas Jacob, a graduate student in the Janda Laboratory who, with Lockner, was a co-lead author of the new paper. "That prompted us to look more closely at the structures of these two compounds."

The two researchers spent months characterizing their own synthesized material and the NCI material, using an array of sophisticated structural analysis tools. With Assistant Professor Vladimir V. Kravchenko of the TSRI Department of Immunology and Microbial Science, Jacob also tested the two compounds' biological effects.

The team eventually concluded that the TIC10 compound from the NCI library does boost TRAIL production in cells and remains promising as the basis for anticancer therapies, but it does not have the structure that was originally published.

The Right Structure

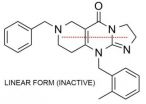

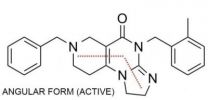

The originally published structure has a core made of three carbon-nitrogen rings in a straight line and does not induce TRAIL activity. The correct, TRAIL-inducing structure differs subtly, with an end ring that sticks out at an angle. In chemists' parlance, the two compounds are constitutional isomers: a linear imidazolinopyrimidinone and an angular imidazolinopyrimidinone.

Ironically, Lockner found that the angular TRAIL-inducing structure was easier to synthesize than the one originally described.

Now, with the correct molecule in hand and a solid understanding of its structure and synthesis, Janda and his team are moving forward with their original plan to study TIC10 in combination with TRAIL-resistance-thwarting molecules as an anticancer therapy.

The therapeutic implications of TIC10 may even go beyond cancer. The angular core of the TRAIL-inducing molecule discovered by Janda's team turns out to be a novel type of a biologically active structure—or "pharmacophore"—from which chemists may now be able to build a new class of candidate drugs, possibly for a variety of ailments.

"One lesson from this has got to be: don't leave your chemists behind," said Janda.

INFORMATION:

Funding for the research, published in a paper titled "Pharmacophore Reassignment for Induction of the Immunosurveillant TRAIL" (DOI: 10.1002/anie.201), was provided by The Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology and TSRI. For more information on the paper, see http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ange.201402133/abstract.

Scripps Research Institute chemists discover structure of cancer drug candidate

2014-05-19

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Weight bias plagues US elections

2014-05-19

EAST LANSING, Mich. --- Overweight political candidates tend to receive fewer votes than their thinner opponents, finds a new study co-authored by a Michigan State University weight bias expert.

While past research has found weight discrimination in schools, businesses, entertainment and other facets of American society, this is the first scientific investigation into whether that bias extends to election outcomes, said Mark Roehling, professor of human resources.

"We found weight had a significant effect on voting behavior," Roehling said. "Additionally, the greater ...

Favoritism, not hostility, causes most discrimination, says UW psychology professor

2014-05-19

Most discrimination in the U.S. is not caused by intention to harm people different from us, but by ordinary favoritism directed at helping people similar to us, according to a theoretical review published online in American Psychologist.

"We can produce discrimination without having any intent to discriminate or any dislike for those who end up being disadvantaged by our behavior," said University of Washington psychologist Tony Greenwald, who co-authored the review with Thomas Pettigrew of the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Greenwald and Pettigrew reviewed ...

UT Dallas study sheds light on how infants understand speech

2014-05-19

A new study from a UT Dallas researcher demonstrates the importance of considering developmental differences when creating programs for cochlear implants in infants.

Dr. Andrea Warner-Czyz, assistant professor in the School of Behavioral and Brain Sciences, recently published the research in the Journal of the Acoustical Society of America.

"This is the first study to show that infants process degraded speech that simulates a cochlear implant differently than older children and adults, which begs for new signal processing strategies to optimize the sound delivered to ...

Brain steroids make good dads

2014-05-19

Testosterone in males is generally associated with aggression and definitely not with good parenting. Insights from a highly social fish can help understand how other androgenic steroids, like testosterone, can shape a male's parenting skills, according to a recent Georgia State University research study.

Once bluebanded gobies become fathers, they stay close to the developing eggs, vigorously fan and rub them until they hatch, and also protect them from mothers who would eat them. By injecting a series of chemicals into the brains of these fathers, the research team ...

Better science for better fisheries management

2014-05-19

Jon Grabowski, a marine science and fisheries expert at Northeastern University's Marine Science Center in Nahant, Massachusetts, has been working with other fisheries scientists as well as economists, social scientists, and policy makers to determine the best strategies for dealing with all of the Northeast region's fisheries that impact habitat, which includes cod, haddock, cusk, scallops, clams and other fish that live near the sea floor and are of significant socioeconomic value to the region.

In research published online last month in the journal Reviews in Fisheries ...

Predicting which stroke patients will be helped -- or harmed -- by clot-busting treatment

2014-05-19

Johns Hopkins researchers say they have developed a technique that can predict — with 95 percent accuracy — which stroke victims will benefit from intravenous, clot-busting drugs and which will suffer dangerous and potentially lethal bleeding in the brain.

Reporting online May 15 in the journal Stroke, the Johns Hopkins team says these predictions were made possible by applying a new method they developed that uses standard magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans to measures damage to the blood-brain barrier that protects the brain from drug exposure.

If further tests ...

Studies find existing and experimental drugs active against MERS-coronavirus

2014-05-19

A series of research articles published ahead of print in the journal Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy have identified a number of existing pharmaceutical drugs and compounds under development that may offer effective therapies against Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS).

In the first study, researchers screened a library of 290 pharmaceutical drugs, either FDA-approved or in advanced clinical development for antiviral activity against the MERS coronavirus (MERS-CoV) and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) in cell culture. They found 27 ...

Report finds site of mega-development project in Mexico is a biodiversity hotspot

2014-05-19

RIVERSIDE, Calif. — Cabo Pulmo is a close-knit community in Baja California Sur, Mexico, and the best preserved coral reef in the Gulf of California. But now the lands adjacent to the reef are under threat from a mega-development project, "Cabo Dorado," should construction go ahead.

Scientists at the University of California, Riverside have published a report on the terrestrial biodiversity of the Cabo Pulmo region that shows the project is situated in an area of extreme conservation value, the center of which is Punta Arena, an idyllic beach setting proposed to be completely ...

Different types of El Nino have different effects on global temperature

2014-05-19

The El Niño–Southern Oscillation is known to influence global surface temperatures, with El Niño conditions leading to warmer temperatures and La Niña conditions leading to colder temperatures. However, a new study in Geophysical Research Letters shows that some types of El Niño do not have this effect, a finding that could explain recent decade-scale slowdowns in global warming.

The authors examine three historical temperature data sets and classify past El Niño events as traditional or central Pacific. They find that global surface temperatures were anomalously warm ...

Does birth control impact women's choice of sexual partners?

2014-05-19

Birth control is used worldwide by more than 60 million women. Since its introduction, it has changed certain aspects of women's lives including family roles, gender roles and social life. New research in The Journal of Sexual Medicine found a link between birth control and women's preferences for psychophysical traits in a sexual mate.

The researchers utilized a PMI (Partner's Masculinity Index) to determine the male traits that women found attractive during the fertile phase of their menstrual cycle. The participants were from Central Italy and divided into two groups ...