(Press-News.org) LA JOLLA, CA – May 22, 2014 – Accumulation of DNA damage can cause aggressive forms of cancer and accelerated aging, so the body's DNA repair mechanisms are normally key to good health. However, in some diseases the DNA repair machinery can become harmful. Scientists led by a group of researchers at The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) in La Jolla, CA, have discovered some of the key proteins involved in one type of DNA repair gone awry.

The focus of the new study, published in the May 22, 2014 edition of the journal Cell Reports, is a protein called Ring1b. The TSRI researchers found that Ring1b promotes fusion between telomeres—repetitive sequences of DNA that act as bumpers on the ends of chromosomes and protect important genetic information. The scientists also showed inhibiting this protein can significantly reduce the burden on cells affected by such telomere dysfunction.

"We are very far from therapy, but I think a lot of the factors we've identified could play key roles in processing dysfunctional telomeres, a key event in tumorigenesis [cancer initiation]," said Eros Lazzerini Denchi, assistant professor at TSRI who led the study.

The Trouble with Telomeres

Humans are born with long telomeres, but these become shorter every time a cell in the body divides. With age, telomeres become very short, especially in tissues that have high proliferation rate.

That's when the problems start. When telomeres become too short, they lose their telomere protective cap and become recognized by the DNA repair machinery proteins. This can lead to the fusion of chromosomes "end-to-end" into a string-like formation.

Joined chromosomes represent an abnormal genomic arrangement that is extremely unstable in dividing cells. Upon cell division, joined chromosomes can rupture, creating new break points that can further re-engage aberrant DNA repair. These cycles of fusion and breakage cause a rampant level of mutations that are fertile ground for cancer.

"You basically scramble the genome, and then you have lots of chances to select very nasty mutations," said Lazzerini Denchi.

Setting a DNA Trap

To understand how to prevent these deleterious fusions, Lazzerini Denchi and his colleagues wanted to identify all the repair factors involved.

The researchers decided to set a trap. Using genetically engineered cells, the researchers were able to remove a telomere binding protein called TRF2. Without TRF2, telomeres are unprotected and DNA repair proteins are recruited to chromosome ends, where they promote chromosome fusions.

The researchers then trapped and isolated all the proteins they found bound to the telomeres. "It was like a fishing expedition, and the bait in our case was the telomeric DNA sequence," said Lazzerini Denchi.

Cristina Bartocci, a postdoctoral fellow in Lazzerini Denchi's lab at the time and first author of the new study, spent more than two years perfecting a technique to identify proteins that flocked to the telomeres. "It was a pretty challenging experiment to perform," she said.

The researchers then separated the proteins from the DNA sequences and sent the proteins to TSRI Professor John Yates's laboratory for mass spectrometry analysis. This analysis revealed 24 known repair proteins and 100 additional proteins whose role in dysfunctional telomeres had not been previously described.

The team then refined their search and took a closer look at the role of the repair factor protein called Ring1b. For the first time, the scientists were able to link Ring1b to the chromosome fusion process. Bartocci said the role of Ring1b in dysfunctional telomere repair was "pretty striking."

"If you don't have Ring1b, the process of fusing the chromosomes is not very efficient," said Lazzerini Denchi.

In addition to Ring1b, the team has found nearly 100 factors that might be related to errors in DNA damage repair. The next step in this research is to further refine the long list of DNA repair factors and study other proteins that could affect human health.

INFORMATION:

In addition to Lazzerini Denchi, Bartocci and Yates, other contributors to the paper, "Isolation of Chromatin from Dysfunctional Telomeres Reveals in Important Roles for Ring1b in NHEJ-Mediated Chromosome Fusions," were Jolene K. Diedrich, Iliana Ouzounov and Julia Li of TSRI, and Andrea Piunti and Diego Pasini of the European Institute of Oncology. See http://www.cell.com/cell-reports/abstract/S2211-1247(14)00289-7

The research was supported by a Pew Scholars Award, the Novartis Advanced Discovery Institute, National Institutes of Health Grants AG038677 and P41 GM103533, the Italian Association for Cancer Research, the Italian Ministry of Health and a fellowship from FIRC.

About The Scripps Research Institute

The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) is one of the world's largest independent, not-for-profit organizations focusing on research in the biomedical sciences. TSRI is internationally recognized for its contributions to science and health, including its role in laying the foundation for new treatments for cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, hemophilia, and other diseases. An institution that evolved from the Scripps Metabolic Clinic founded by philanthropist Ellen Browning Scripps in 1924, the institute now employs about 3,000 people on its campuses in La Jolla, CA, and Jupiter, FL, where its renowned scientists—including three Nobel laureates—work toward their next discoveries. The institute's graduate program, which awards PhD degrees in biology and chemistry, ranks among the top ten of its kind in the nation. For more information, see http://www.scripps.edu.

TSRI scientists catch misguided DNA-repair proteins in the act

2014-05-22

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Univ. of MD researchers identify fat-storage gene mutation that may increase diabetes risk

2014-05-22

BALTIMORE – May 21, 2014. Researchers at the University of Maryland School of Medicine have identified a mutation in a fat-storage gene that appears to increase the risk for type 2 diabetes and other metabolic disorders, according to a study published online today in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The researchers discovered the mutation in the hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL) gene by studying the DNA of more than 2,700 people in the Old Order Amish community in Lancaster County, Pa. HSL is a key enzyme involved in breaking down stored fat (triglycerides) into fatty ...

Ka'ena Volcano: First building block for O'ahu discovered

2014-05-22

Boulder, Colo., USA – Researcher John Sinton of the University of Hawai'i along with colleagues from the Monterrey Bay Aquarium and the French National Center for Scientific Research have announced the discovery of an ancient Hawaiian volcano. Now located in a region of shallow bathymetry extending about 100 km WNW from Ka'ena Point at the western tip of O'ahu, this volcano, which they have named Ka'ena, would have risen about 1,000 meters above sea level 3.5 million years ago.

Sinton and colleagues have found compelling evidence beneath the sea that this long-lived ...

Intuitions about the causes of rising obesity are often wrong, researchers report

2014-05-22

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — Everything you think you know about the causes of rising obesity in the U.S. might be wrong, researchers say in a new report.

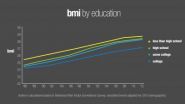

Contrary to popular belief, people are exercising more today, have more leisure time and better access to fresh, affordable food – including fruits and vegetables – than they did in past decades. And while troubling disparities exist among various groups, most economic, educational, and racial or ethnic groups have seen their obesity levels rise at similar rates since the mid-1980s, the researchers report.

The new analysis appears ...

Review says inexpensive food a key factor in rising obesity

2014-05-22

ATLANTA May 22, 2014—A new review summarizes what is known about economic factors tied to the obesity epidemic in the United States and concludes many common beliefs are wrong. The review, authored by Roland Sturm, PhD of RAND Corporation and Ruopeng An, PhD, of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, notes that paradoxically, rising obesity rates coincided with increases in leisure time, increased fruit and vegetable availability, and increased exercise uptake. The review appears early online in CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians and finds at least one factor ...

Scientists find new way to combat drug resistance in skin cancer

2014-05-22

RAPID RESISTANCE to vemurafenib – a treatment for a type of advanced melanoma, the deadliest form of skin cancer – could be prevented by blocking a druggable family of proteins, according to research* published in Nature Communications today (Thursday).

Scientists at the Cancer Research UK Manchester Institute, based at the University of Manchester, have revealed the MLK family of four enzymes 'undoes' the tumour-shrinking effects of vemurafenib**.

Around half of metastatic melanomas – aggressive skin cancer that has spread to other parts of the body – are caused by ...

Canada funds 65 innovative health projects to help save every woman, every child

2014-05-22

Grand Challenges Canada, funded by the Government of Canada, today announces investments of $12 million in projects worldwide, aimed squarely at improving the health and saving the lives of mothers, newborns and children in developing countries.

From a "lucky iron fish" placed in tens of thousands of Asian cooking pots to reduce anemia, to "motherhood insurance" to ensure that poverty doesn't impede emergency care if needed during a baby's delivery, to kits for home farming edible insects to improve nutrition in slums of Africa and Latin America, the 65 imaginative projects ...

New insights into premature ejaculation could lead to better diagnosis and treatment

2014-05-22

There are many misconceptions and unknowns about premature ejaculation in the medical community and the general population. Two papers, both being published simultaneously in Sexual Medicine and the Journal of Sexual Medicine, provide much-needed answers that could lead to improved diagnosis and treatment for affected men.

Premature ejaculation can cause significant personal and interpersonal distress to a man and his partner. While it has been recognized as a syndrome for well over 100 years, the clinical definition of premature ejaculation has been vague, ambiguous, ...

Could cannabis curb seizures? Experts weed through the evidence

2014-05-22

The therapeutic potential of medical marijuana and pure cannabidiol (CBD), an active substance in the cannabis plant, for neurologic conditions is highly debated. A series of articles published in Epilepsia, a journal of the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE), examine the potential use of medical marijuana and CBD in treating severe forms of epilepsy such as Dravet syndrome.

In a case study, Dr. Edward Maa, Chief of the Comprehensive Epilepsy Program at Denver Health in Denver, Colo., details one mother's experience of providing medical marijuana to her child ...

Scientists announce top 10 new species for 2014

2014-05-22

SYRACUSE, N.Y. — An appealing carnivorous mammal, a 12-meter-tall tree that has been hiding in plain sight and a sea anemone that lives under an Antarctic glacier are among the species identified by the SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry's (ESF) International Institute for Species Exploration (IISE) as the top 10 species discovered last year.

An international committee of taxonomists and related experts selected the top 10 from among the approximately 18,000 new species named during the previous year and released the list May 22 to coincide with the birthday, ...

Temperature influences gender of offspring

2014-05-22

Whether an insect will have a male or female offspring depends on the weather, according to a study led by Joffrey Moiroux and Jacques Brodeur of the University of Montreal's Department of Biological Sciences. The research involved experimenting with a species of oophagous parasitoid (Trichogramma euproctidis), an insect that lays its eggs inside a host insect that will be consumed by the future larvae. "We know that climate affects the reproductive behaviour of insects. But we never clearly demonstrated the effects of climate change on sex allocation in parasitoids," Moiroux ...