(Press-News.org) Every once in a while in the U.S., bacterial meningitis seems to crop up out of nowhere, claiming a young life. Part of the disease's danger is the ability of the bacteria to evade the body's immune system, but scientists are now figuring out how the pathogen hides in plain sight. Their findings, which could help defeat these bacteria and others like it, appear in the Journal of the American Chemical Society.

Linda Columbus and colleagues explain that the bacteria Neisseria meningitidis, one cause of meningitis, and its cousin Neisseria gonorrhoeae, which is responsible for gonorrhea, have key-like proteins that allow them to enter human cells and do their damage. Gonorrhea can be cured, though one type of the responsible bacteria has reached "superbug" status, becoming resistant to known drugs. If meningitis is not treated immediately with antibiotics, it can cause severe disability and death. In a search for new ways to treat these diseases, scientists are looking more closely at how the bacteria sneak around in the body undetected. When someone gets an infection, specific proteins — called antigens — that stud the pathogen's outer layer usually raise an alarm, and the body's immune system goes on the attack. But these two kinds of Neisseria bacteria can elude the body's look-out cells, and Columbus' team wanted to know how.

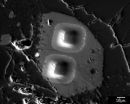

They combined two approaches to figure out the architecture of one of the bacteria's outer proteins that help it gain entry into human cells. They found that the protein's outer loops that jostle against each other, causing their structure to constantly change. This shape-shifting makes for a kind of camouflage that hides them from the body's sentinels, at the same time preserving its ability to bind to and enter a person's cells. This deeper understanding could help lead to new treatments for bacterial diseases, the scientists state.

INFORMATION:

The authors acknowledge funding from the National Science Foundation, Cottrell Scholar Award, the University of Virginia nanoSTAR and the National Institutes of Health.

The American Chemical Society is a nonprofit organization chartered by the U.S. Congress. With more than 161,000 members, ACS is the world's largest scientific society and a global leader in providing access to chemistry-related research through its multiple databases, peer-reviewed journals and scientific conferences. Its main offices are in Washington, D.C., and Columbus, Ohio.

To automatically receive news releases from the American Chemical Society, contact newsroom@acs.org.

Follow us: Twitter Facebook

Sneaky bacteria change key protein's shape to escape detection

2014-05-28

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Artificial lung the size of a sugar cube

2014-05-28

This news release is available in German.

Lung cancer is a serious condition. Once patients are diagnosed with it, chemotherapy is often their only hope. But nobody can accurately predict whether or not this treatment will help. To start with, not all patients respond to a course of chemotherapy in exactly the same way. And then there's the fact that the systems drug companies use to test new medications leave a lot to be desired. "Animal models may be the best we have at the moment, but all the same, 75 percent of the drugs deemed beneficial when tested on animals ...

Water in moon rocks provides clues and questions about lunar history

2014-05-28

A recent review of hundreds of chemical analyses of Moon rocks indicates that the amount of water in the Moon's interior varies regionally – revealing clues about how water originated and was redistributed in the Moon. These discoveries provide a new tool to unravel the processes involved in the formation of the Moon, how the lunar crust cooled, and its impact history.

This is not liquid water, but water trapped in volcanic glasses or chemically bound in mineral grains inside lunar rocks. Rocks originating from some areas in the lunar interior contain much more water ...

Ultraviolet cleaning reduces hospital superbugs by 20 percent: Study

2014-05-28

Washington, DC, May 27, 2014 – Healthcare-associated vancomycin-resistant enterococcus (VRE), methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Clostridium difficile (CD), and other multidrug-resistant organisms (MDRO) were decreased among patients after adding ultraviolet environmental disinfection (UVD) to the cleaning regimen, according to a study published in the June issue of the American Journal of Infection Control, the official publication of the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC).

In this retrospective study led by the ...

What can plants reveal about gene flow? That it's an important evolutionary force

2014-05-28

A plant breeder discovers his experimental crops have been "contaminated" with genes from a neighboring field. New nasty weeds sometimes evolve directly from natural crosses between domesticated species and their wild relatives. A rare plant is threatened due to its small population size and restricted range. What do all these situations have in common? They illustrate the important role of gene flow among populations and its potential consequences. Although gene flow was recognized by a few scientists as a significant evolutionary force as early as the 1940s, its relative ...

In Africa, STI testing could boost HIV prevention

2014-05-28

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — To maximize HIV prevention efforts in South Africa and perhaps the broader region, public health officials should consider testing for other sexually transmitted infections when they test for HIV, according to a new paper in the journal Sexually Transmitted Infections.

STIs can make HIV easier to transmit even after antiretroviral therapy has begun, so rooting out STI co-infections in patients should improve HIV prevention. The new study led by Brown University public health researchers emphasizes that sooner is indeed better than ...

Variety in diet can hamper microbial diversity in the gut

2014-05-28

AUSTIN, Texas — Scientists from The University of Texas at Austin and five other institutions have discovered that the more diverse the diet of a fish, the less diverse are the microbes living in its gut. If the effect is confirmed in humans, it could mean that the combinations of foods people eat can influence the diversity of their gut microbes.

The research could have implications for how probiotics and diet are used to treat diseases associated with the bacteria in human digestive systems.

A large body of research has shown that the human microbiome, the collection ...

Melting Arctic opens new passages for invasive species

2014-05-28

For the first time in roughly 2 million years, melting Arctic sea ice is connecting the north Pacific and north Atlantic oceans. The newly opened passages leave both coasts and Arctic waters vulnerable to a large wave of invasive species, biologists from the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center assert in a commentary published May 28 in Nature Climate Change.

Two new shipping routes have opened in the Arctic: the Northwest Passage through Canada, and the Northern Sea Route, a 3000-mile stretch along the coasts of Russia and Norway connecting the Barents and Bering ...

3,000 rice genome sequences made publicly available on World Hunger Day

2014-05-28

The open-access, open-data journal GigaScience (published by BGI and Biomed Central), announces today the publication of an article on the genome sequencing of 3000 rice strains along with the release of this entire dataset in a citable format in journal's affiliated open-access database, GigaDB. The publication and release of this enormous data set (which quadruples the current amount of publicly available rice sequence data) coincides with World Hunger Day to highlight one of the primary goals of this project— to develop resources that will aid in improving global food ...

High-status co-eds use 'slut discourse' to assert class advantage

2014-05-28

WASHINGTON, DC, May 27, 2014 — A new study suggests that high-status female college students employ "slut discourse" — defining their styles of femininity and approaches to sexuality as classy rather than trashy or slutty — to assert class advantage and put themselves in a position where they can enjoy sexual exploration with few social consequences.

"Viewing women only as victims of men's sexual dominance fails to hold women accountable for the roles they play in reproducing social inequalities," said lead author Elizabeth A. Armstrong, an associate professor of sociology ...

Prehistoric birds lacked in diversity

2014-05-28

Birds come in astounding variety—from hummingbirds to emus—and behave in myriad ways: they soar the skies, swim the waters, and forage the forests. But this wasn't always the case, according to research by scientists at the University of Chicago and the Field Museum.

The researchers found a striking lack of diversity in the earliest known fossil bird fauna (a set of species that lived at about the same time and in the same habitat). "There were no swans, no swallows, no herons, nothing like that. They were pretty much all between a sparrow and a crow," said Jonathan ...