(Press-News.org) One of the reasons we don't yet have self-driving cars and mini-helicopters delivering online purchases is that autonomous vehicles tend not to perform well under pressure. A system that can flawlessly parallel park at 5 mph may have trouble avoiding obstacles at 35 mph.

Part of the problem is the time it takes to produce and interpret camera data. An autonomous vehicle using a standard camera to monitor its surroundings might take about a fifth of a second to update its location. That's good enough for normal operating conditions but not nearly fast enough to handle the unexpected.

Andrea Censi, a research scientist in MIT's Laboratory for Information and Decision Systems, thinks the solution could be to supplement cameras with a new type of sensor called an event-based (or "neuromorphic") sensor, which can take measurements a million times a second.

At this year's International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Censi and Davide Scaramuzza of the University of Zurich present the first state-estimation algorithm — the type of algorithm robots use to gauge their position — to process data from event-based sensors. A robot running their algorithm could update its location every thousandth of a second or so, allowing it to perform much more nimble maneuvers.

"In a regular camera, you have an array of sensors, and then there is a clock," Censi explains. "If you have a 30-frames-per-second camera, every 33 milliseconds the clock freezes all the values, and then the values are read in order." With an event-based sensor, by contrast, "each pixel acts as an independent sensor," Censi says. "When a change in luminance — in either the plus or minus direction — is larger than a threshold, the pixel says, 'I see something interesting' and communicates this information as an event. And then it waits until it sees another change."

Featured event

When a standard state-estimation algorithm receives an image from a robot-mounted camera, it first identifies "features": gradations of color or shade that it takes to be boundaries between objects. Then it selects a subset of those features that it considers unlikely to change much with new perspectives.

Thirty milliseconds later, when the camera fires again, the algorithm performs the same type of analysis and starts trying to match features between the two images. This is a trial-and-error process, which can take anywhere from 50 to 250 milliseconds, depending on how dramatically the scene has changed. Once it's matched features, the algorithm can deduce from their changes in position how far the robot has moved.

Censi and Scaramuzza's algorithm supplements camera data with events reported by an event-based sensor, which was designed by their collaborator Tobi Delbruck of the Institute for Neuroinformatics in Zurich. The new algorithm's first advantage is that it doesn't have to identify features: Every event is intrinsically a change in luminance, which is what defines a feature. And because the events are reported so rapidly — every millionth of a second — the matching problem becomes much simpler. There aren't as many candidate features to consider because the robot can't have moved very far.

Moreover, the algorithm doesn't try to match all the features in an image at once. For each event, it generates a set of hypotheses about how far the robot has moved, corresponding to several candidate features. After enough events have accumulated, it simply selects the hypothesis that turns up most frequently.

In experiments involving a robot with a camera and an event-based sensor mounted on it, their algorithm proved just as accurate as existing state-estimation algorithms.

Getting onboard

One of the inspirations for the new work, Censi says, was a series of recent experiments by Vijay Kumar at the University of Pennsylvania, which demonstrated that quadrotor helicopters — robotic helicopters with four sets of rotors — could perform remarkably nimble maneuvers. But in those experiments, Kumar gauged the robots' location using a battery of external cameras that captured 1,000 exposures a second. Censi believes that his and Scaramuzza's algorithm would allow a quadrotor with onboard sensors to replicate Kumar's results.

Now that he and his colleagues have a reliable state-estimation algorithm, Censi says, the next step is to develop a corresponding control algorithm — an algorithm that decides what to do on the basis of the state estimates. That's the subject of an ongoing collaboration with Emilio Frazzoli, a professor of aeronautics and astronautics at MIT.

INFORMATION:

Written by Larry Hardesty, MIT News Office

Think fast, robot

Algorithm that harnesses data from a new sensor could make autonomous robots more nimble

2014-05-29

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Minority entrepreneurs face discrimination when seeking loans

2014-05-29

A disheartening new study from researchers at Utah State University, BYU and Rutgers University reveals that discrimination is still tainting the American Dream for minorities.

The three-part research article, which appears online in the Journal of Consumer Research, finds that minorities seeking small business loans are treated differently than their white counterparts, despite having identical qualifications on paper.

While discrimination in housing, employment and education is well documented, the study shows that minorities also face discrimination in the marketplace. ...

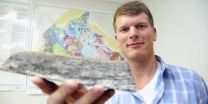

Four-billion-year-old rocks yield clues about Earth's earliest crust

2014-05-29

(Edmonton) It looks like just another rock, but what Jesse Reimink holds in his hands is a four-billion-year-old chunk of an ancient protocontinent that holds clues about how the Earth's first continents formed.

The University of Alberta geochemistry student spent the better part of three years collecting and studying ancient rock samples from the Acasta Gneiss Complex in the Northwest Territories, part of his PhD research to understand the environment in which they formed.

"The timing and mode of continental crust formation throughout Earth's history is a controversial ...

Diesel bus alternative

2014-05-29

Electric school buses that feed the power grid could save school districts millions of dollars — and reduce children's exposure to diesel fumes — based on recent research by the University of Delaware's College of Earth, Ocean, and Environment (CEOE).

A new study examines the cost-effectiveness of electric school buses that discharge their batteries into the electrical grid when not in use and get paid for the service. The technology, called vehicle-to-grid (V2G), was pioneered at UD and is being tested with electric cars in a pilot project.

Adapting the system for ...

Stress degrades sperm quality

2014-05-29

Psychological stress is harmful to sperm and semen quality, affecting its concentration, appearance, and ability to fertilize an egg, according to a study led by researchers Columbia University's Mailman School of Public Health and Rutgers School of Public Health. Results are published online in the journal Fertility and Sterility.

According to the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, infertility affects men and women equally, and semen quality is a key indicator of male fertility.

"Men who feel stressed are more likely to have lower concentrations of sperm ...

Rare skin cancer on palms and soles more likely to come back compared to other melanomas

2014-05-29

A rare type of melanoma that disproportionately attacks the palms and soles and under the nails of Asians, African-Americans, and Hispanics, who all generally have darker skins, and is not caused by sun exposure, is almost twice as likely to recur than other similar types of skin cancer, according to results of a study in 244 patients.

The finding about acral lentiginous melanoma, as the potentially deadly cancer is known, is part of a study to be presented May 31 by researchers at the Perlmutter Cancer Center of NYU Langone at the annual meeting of the American Society ...

Better to be bullied than ignored in the workplace: Study

2014-05-29

Being ignored at work is worse for physical and mental well-being than harassment or bullying, says a new study from the University of British Columbia's Sauder School of Business.

Researchers found that while most consider ostracism less harmful than bullying, feeling excluded is significantly more likely to lead job dissatisfaction, quitting and health problems.

"We've been taught that ignoring someone is socially preferable--if you don't have something nice to say, don't say anything at all," says Sauder Professor Sandra Robinson, who co-authored the study. "But ...

Diet and exercise in cancer prevention and treatment: Focus of APNM special

2014-05-29

"Cancer is a leading cause of mortality worldwide and for the foreseeable future...."

This Special Issue titled "The role of diet, body composition, and physical activity on cancer prevention, treatment, and survivorship" comprises both invited reviews and original papers investigating various themes such as the role of omega-3 fatty acids, amino acids, cancer cachexia, muscle health, exercise training, adiposity and body composition.

The Special Editors were David Ma, Department of Human Health and Nutritional Sciences, College of Biological Science, University of ...

'Listening' helps scientists track bats without exposing the animals to disease

2014-05-29

A fungus that infects bats as they hibernate is killing them by the millions, placing three species in the East perilously close to being declared endangered — or perhaps beyond, towards extinction.

How to know the actual condition of the populations of different bat species is challenging.

Now a team of researchers from Virginia Tech, the U.S. Geological Survey, the U.S. Army Installation Command, and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has determined the most efficient ways to improve and modify a sampling technique that is already available.

Acoustic monitoring — ...

Family support may improve adherence to CPAP therapy for sleep apnea

2014-05-29

DARIEN, IL – A new study suggests that people with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) who are single or have unsupportive family relationships may be less likely to adhere to continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy.

Results show that individuals who were married or living with a partner had better CPAP adherence after the first three months of treatment than individuals who were single. Higher ratings of family relationship quality also were associated with better adherence. Results were adjusted for potential confounding factors including age, gender and body ...

Heavy airplane traffic potentially a major contributor to pollution in Los Angeles

2014-05-29

Congested freeways crawling with cars and trucks are notorious for causing smog in Los Angeles, but a new study finds that heavy airplane traffic can contribute even more pollution, and the effect continues for up to 10 miles away from the airport. The report, published in the ACS journal Environmental Science & Technology, has serious implications for the health of residents near Los Angeles International Airport (LAX) and other airports around the world.

Scott Fruin, D.Env. P.E., Neelakshi Hudda and colleagues note that past research has measured pollution from air ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Smartphone app can help men last longer in bed

Longest recorded journey of a juvenile fisher to find new forest home

Indiana signs landmark education law to advance data science in schools

A new RNA therapy could help the heart repair itself

The dehumanization effect: New PSU research examines how abusive supervision impacts employee agency and burnout

New gel-based system allows bacteria to act as bioelectrical sensors

The power of photonics

From pioneer to leader: Alex Zhavoronkov chairs precision aging discussion and presents Luminary Award to OpenAI president at PMWC 2026

Bursting cancer-seeking microbubbles to deliver deadly drugs

In a South Carolina swamp, researchers uncover secrets of firefly synchrony

American Meteorological Society and partners issue statement on public availability of scientific evidence on climate change

How far will seniors go for a doctor visit? Often much farther than expected

Selfish sperm hijack genetic gatekeeper to kill healthy rivals

Excessive smartphone use associated with symptoms of eating disorder and body dissatisfaction in young people

‘Just-shoring’ puts justice at the center of critical minerals policy

A new method produces CAR-T cells to keep fighting disease longer

Scientists confirm existence of molecule long believed to occur in oxidation

The ghosts we see

ACC/AHA issue updated guideline for managing lipids, cholesterol

Targeting two flu proteins sharply reduces airborne spread

Heavy water expands energy potential of carbon nanotube yarns

AMS Science Preview: Mississippi River, ocean carbon storage, gender and floods

High-altitude survival gene may help reverse nerve damage

Spatially decoupling active-sites strategy proposed for efficient methanol synthesis from carbon dioxide

Recovery experiences of older adults and their caregivers after major elective noncardiac surgery

Geographic accessibility of deceased organ donor care units

How materials informatics aids photocatalyst design for hydrogen production

BSO recapitulates anti-obesity effects of sulfur amino acid restriction without bone loss

Chinese Neurosurgical Journal reports faster robot-assisted brain angiography

New study clarifies how temperature shapes sex development in leopard gecko

[Press-News.org] Think fast, robotAlgorithm that harnesses data from a new sensor could make autonomous robots more nimble