(Press-News.org) The combined action of two enzymes, Srs2 and Exo1, prevents and repairs common genetic mutations in growing yeast cells, according to a new study led by scientists at NYU Langone Medical Center.

Because such mechanisms are generally conserved throughout evolution, at least in part, researchers say the findings suggest that a similar DNA repair kit may exist in humans and could serve as a target for controlling some cancers and treating a rare, enzyme-linked genetic disorder called Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome. The syndrome, an often fatal neurological condition, is found in only a few families in small towns in Italy, Algeria and Japan, and among North American Cree Indians.

In a report to be published in the journal Nature online June 1, NYU Langone researchers, aided by colleagues at Yale University, found that the paired enzyme action prevents and repairs mistakes made during DNA replication, when molecular subunits known as rNMPs get inserted into DNA. The rNMPs are building blocks of DNA's chemical cousin RNA, which is the key intermediary involved in making all proteins from DNA.

Researchers say while some misplaced rNMPs naturally occur — and are repaired — as DNA is replicated during cell growth, enzymes quickly recognize such foreign intruders as lesions. If not removed, such lesions raise the likelihood of mutations in the DNA code, which if allowed to accumulate, create genomic instability in yeast and human cells, and can lead to cell death and cancer-promoting immune reactions.

"Taking our cue from yeast, which shares a third of its genetic make-up with humans, our study shows for the first time that a very robust backup DNA repair mechanism is in place to deal with common rNMP-induced mutations," says senior study investigator and NYU Langone yeast geneticist Hannah Klein, PhD. "Without a robust backup system for DNA repair, cells will die."

Among the study's key findings was that one of the enzymes, Srs2, helps open up the tightly bound, ladder-like yeast DNA structure so that the other enzyme, Exo1, can cleave out any misplaced rNMPs. Such rNMP misinsertions during replication, scientists say, contaminate DNA and are often lethal structural alterations. Both enzymes were previously known to play a role in DNA replication and repair, but the scientists say this is the first evidence of their role in preventing and correcting rNMP-derived mutations.

Moreover, the research team found that the Srs2-Exo1cell-repair mechanism prevents mutations from accelerating in yeast already deficient in a third enzyme coded by the gene RNaseH2. That enzyme serves as the primary removal mechanism for rNMPs during cell growth, a major role in DNA repair. But in yeast deficient in both the RNaseH2 enzyme and Srs2, the number of mutations, chromosome losses, and chromosome breakages rise 10-fold.

According to Dr. Klein, interim chair of biochemistry and molecular pharmacology at NYU Langone, her team's study is also the first to show how Srs2 and Exo1 backs up the routine rNMP maintenance function of the RNaseH2 enzyme, highlighting nature's constant need to balance cell growth, genetic mutation and DNA repair in preventing disease and cell death.

Dr. Klein cautions that while no known human Srs2 counterpart exists, Exo1 is found in human cells, so it is likely that a similar backup DNA repair mechanism exists in people. And if further testing shows that its repair function can be manipulated in humans, the enzyme mechanism could be used as a basis to stall or reverse cancers derived from RNaseH2 mutations. Dr. Klein says breaking down how tumors develop in RNaseH2-deficient yeast cells is critical to formulating and testing potential treatments for people.

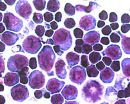

Other research has implicated overproduction of RNase H2 as one of several genetic features of many cancers, including cancers of the bladder, brain, breast, head, and neck squamous cell carcinomas, as well as leukemias (T- and B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia and acute myeloid leukemia), melanomas, and seminomas.

Even more specifically, she says, the enzyme repair mechanism could potentially be used to decipher and counteract the root causes of RNaseH2 enzyme deficiency, which in humans is known to be one of the main hereditary signatures behind Aicardi -Goutieres syndrome. The syndrome causes spinal inflammation and brain shrinkage, fatally stalling physical and mental development in early childhood. Although rare and currently untreatable, the disease afflicts hundreds in isolated communities where inbreeding among families has occurred and when both parents have RNaseH2 or other Aicardi -Goutieres-related mutations.

For the study, lead investigator and fellow yeast geneticist Catherine Potenski, PhD, monitored how various mutant yeast strains grew in the laboratory, including those deficient in the RNaseH2 enzyme and Srs2. (Dr. Klein's lab in the late 1980s was the first to isolate RNaseH2 mutations in yeast.)

Dr. Potenski, a postdoctoral fellow at NYU Langone, says yeast strains deficient in both enzymes accumulated mutations and did not grow well, while those depleted of only the RNaseH2 enzyme, were able to minimize mutations and continue growing. However, in experiments with Exo1, its removal spiked mutations in RNaseH2-deficient strains, while depletion of Srs2 had no worsening effect. This evidence confirmed to researchers that Srs2 and Exo1 acted together to prevent mutations in RNaseH2-deficient cells.

Analysis by colleagues at Yale later confirmed the linked action between Srs2 and Exo1, showing how Srs2 stimulated Exo1 to act on yeast DNA, allowing for the cleaving and repair of rNMP lesions.

Dr. Potenski says her latest studies of Srs2, Exo1, and RNaseH2 enzymes should also serve as a reminder to other researchers that known enzymes may have many roles in the cell life cycle, some of which are not yet known, and that even more backup roles could be found.

Dr. Potenski says the team next plans to investigate what other biological factors may act on Exo1, as a possible third backup repair mechanism, and to investigate what factors might trigger RNaseH2 mutations more prone to lead to cancer.

INFORMATION:

Funding support for the study was provided by the US National Institutes of Health. Corresponding federal grant numbers are R01 GM053738, R01 ES007061, and K99 ES021441.

In addition to Drs. Klein and Potenski, other researchers involved in this study were Hengyao Niu, PhD, and Patrick Sung, DPhil, PhD, at Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

For more information, go to:

http://www.med.nyu.edu/biosketch/kleinh01

http://www.nature.com/nm/journal/vaop/ncurrent/index.html

About NYU Langone Medical Center:

NYU Langone Medical Center, a world-class, patient-centered, integrated academic medical center, is one of the nation's premier centers for excellence in clinical care, biomedical research, and medical education. Located in the heart of Manhattan, NYU Langone is composed of four hospitals—Tisch Hospital, its flagship acute care facility; Rusk Rehabilitation; the Hospital for Joint Diseases, the Medical Center's dedicated inpatient orthopaedic hospital; and Hassenfeld Children's Hospital, a comprehensive pediatric hospital supporting a full array of children's health services across the Medical Center—plus the NYU School of Medicine, which since 1841 has trained thousands of physicians and scientists who have helped to shape the course of medical history. The Medical Center's tri-fold mission to serve, teach, and discover is achieved 365 days a year through the seamless integration of a culture devoted to excellence in patient care, education, and research. For more information, go to http://www.NYULMC.org, and interact with us on Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube.

Media Inquiries:

David March

212.404.3528│david.march@nyumc.org

Paired enzyme action in yeast reveals backup system for DNA repair

Study suggests new targets for treating rare genetic disorder and human cancer

2014-06-01

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Pitt team first to detect exciton in metal

2014-06-01

PITTSBURGH—University of Pittsburgh researchers have become the first to detect a fundamental particle of light-matter interaction in metals, the exciton. The team will publish its work online June 1 in Nature Physics.

Mankind has used reflection of light from a metal mirror on a daily basis for millennia, but the quantum mechanical magic behind this familiar phenomenon is only now being uncovered.

Physicists describe physical phenomena in terms of interactions between fields and particles, says lead author Hrvoje Petek, Pitt's Richard King Mellon Professor in the Department ...

Subtle change in DNA, protein levels determines blond or brunette tresses, study finds

2014-06-01

STANFORD, Calif. — A molecule critical to stem cell function plays a major role in determining human hair color, according to a study from the Stanford University School of Medicine.

The study describes for the first time the molecular basis for one of our most noticeable traits. It also outlines how tiny DNA changes can reverberate through our genome in ways that may affect evolution, migration and even human history.

"We've been trying to track down the genetic and molecular basis of naturally occurring traits — such as hair and skin pigmentation — in fish and humans ...

International collaboration replicates amplification of cosmic magnetic fields

2014-06-01

VIDEO:

This video simulation shows how a laser that illuminates a small carbon rod launches a complex flow, consisting of supersonic shocks and turbulent flow. When the grid is present, turbulence...

Click here for more information.

Astrophysicists have established that cosmic turbulence could have amplified magnetic fields to the strengths observed in interstellar space.

"Magnetic fields are ubiquitous in the universe," said Don Lamb, the Robert A. Millikan Distinguished ...

Researchers discover hormone that controls supply of iron in red blood cell production

2014-06-01

A UCLA research team has discovered a new hormone called erythroferrone, which regulates the iron supply needed for red blood-cell production.

Iron is an essential functional component of hemoglobin, the molecule that transports oxygen throughout the body. Using a mouse model, researchers found that erythroferrone is made by red blood-cell progenitors in the bone marrow in order to match iron supply with the demands of red blood-cell production. Erythroferrone is greatly increased when red blood-cell production is stimulated, such as after bleeding or in response to anemia.

The ...

Leptin also influences brain cells that control appetite, Yale researchers find

2014-06-01

Twenty years after the hormone leptin was found to regulate metabolism, appetite, and weight through brain cells called neurons, Yale School of Medicine researchers have found that the hormone also acts on other types of cells to control appetite.

Published in the June 1 issue of Nature Neuroscience, the findings could lead to development of treatments for metabolic disorders such as obesity and diabetes.

"Up until now, the scientific community thought that leptin acts exclusively in neurons to modulate behavior and body weight," said senior author Tamas Horvath, the ...

Mayo Clinic: Ovarian cancer subtypes may predict response to bevacizumab

2014-06-01

CHICAGO — Molecular sequencing could identify ovarian cancer patients who are most likely to benefit from treatment with bevacizumab (Avastin), a Mayo Clinic-led study has found. Results of the research were presented today at the 2014 American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting.

The addition of bevacizumab to standard therapy extended progression-free survival more for ovarian cancer patients with molecular subtypes labeled as "proliferative" or "mesenchymal" compared to those with subtypes labeled as "immunoreactive" or "differentiated," says Sean Dowdy, M.D., ...

Oncologists: How to talk with your pathologist about cancer molecular testing

2014-06-01

As targeted therapies become more available, increasing opportunity exists to match treatments to the genetics of a specific cancer. But in order to make this match, oncologists have to know these genetics. This requires molecular testing of patient samples. An education session presented today at the American Society for Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting 2014 details the challenges in this process and makes recommendations that oncologists can use to ensure their patients' samples are properly tested, helping to pair patients with the best possible treatments.

"The ...

Chemotherapy following radiation treatment improves progression-free survival

2014-06-01

CHICAGO — A chemotherapy regimen consisting of procarbazine, CCNU, and vincristine (PCV) administered following radiation therapy improved progression-free survival and overall survival in adults with low-grade gliomas, a form of brain cancer, when compared to radiation therapy alone. The findings were part of the results of a Phase III clinical trial presented today at the 2014 American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting by the study's primary author Jan Buckner, M.D., deputy director, Cancer Practice, at Mayo Clinic Cancer Center.

"On average, patients who ...

New report estimates nearly 19 million cancer survivors in the US by 2024

2014-06-01

ATLANTA – June 1, 2014 – The number of cancer survivors in the United States, currently estimated to be 14.5 million, will grow to almost 19 million by 2024, according to an updated report by the American Cancer Society. The second edition of Cancer Treatment & Survivorship Facts & Figures, 2014-2015 and an accompanying journal article published in CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians find that even though cancer incidence rates have been decreasing for ten years, the number of cancer survivors is growing. This is the result of increases in cancer diagnoses driven by the ...

Reducing emissions will be the primary way to fight climate change, UCLA-led study finds

2014-06-01

Forget about positioning giant mirrors in space to reduce the amount of sunlight being trapped in the earth's atmosphere or seeding clouds to reduce the amount of light entering earth's atmosphere. Those approaches to climate engineering aren't likely to be effective or practical in slowing global warming.

A new report by professors from UCLA and five other universities concludes that there's no way around it: We have to cut down the amount of carbon being released into the atmosphere. The interdisciplinary team looked at a range of possible approaches to dissipating ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

One-third of Americans making financial trade-offs to pay for healthcare

Researchers clarify how ketogenic diets treat epilepsy, guiding future therapy development

PsyMetRiC – a new tool to predict physical health risks in young people with psychosis

Island birds reveal surprising link between immunity and gut bacteria

Research presented at international urology conference in London shows how far prostate cancer screening has come

Further evidence of developmental risks linked to epilepsy drugs in pregnancy

Cosmetic procedures need tighter regulation to reduce harm, argue experts

How chaos theory could turn every NHS scan into its own fortress

Vaccine gaps rooted in structural forces, not just personal choices: SFU study

Safer blood clot treatment with apixaban than with rivaroxaban, according to large venous thrombosis trial

Turning herbal waste into a powerful tool for cleaning heavy metal pollution

Immune ‘peacekeepers’ teach the body which foods are safe to eat

AAN issues guidance on the use of wearable devices

In former college athletes, more concussions associated with worse brain health

Racial/ethnic disparities among people fatally shot by U.S. police vary across state lines

US gender differences in poverty rates may be associated with the varying burden of childcare

3D-printed robotic rattlesnake triggers an avoidance response in zoo animals, especially species which share their distribution with rattlers in nature

Simple ‘cocktail’ of amino acids dramatically boosts power of mRNA therapies and CRISPR gene editing

Johns Hopkins scientists engineer nanoparticles able to seek and destroy diseased immune cells

A hidden immune circuit in the uterus revealed: Findings shed light on preeclampsia and early pregnancy failure

Google Earth’ for human organs made available online

AI assistants can sway writers’ attitudes, even when they’re watching for bias

Still standing but mostly dead: Recovery of dying coral reef in Moorea stalls

3D-printed rattlesnake reveals how the rattle is a warning signal

Despite their contrasting reputations, bonobos and chimpanzees show similar levels of aggression in zoos

Unusual tumor cells may be overlooked factors in advanced breast cancer

Plants pause, play and fast forward growth depending on types of climate stress

University of Minnesota scientists reveal how deadly Marburg virus enters human cells, identify therapeutic vulnerability

Here's why seafarers have little confidence in autonomous ships

MYC amplification in metastatic prostate cancer associated with reduced tumor immunogenicity

[Press-News.org] Paired enzyme action in yeast reveals backup system for DNA repairStudy suggests new targets for treating rare genetic disorder and human cancer