(Press-News.org) JACKSONVILLE, Fla. — Neuroscientists at Mayo Clinic in Florida and at Aarhus University in Denmark have shed light on why neurons in the brain's reward system can be miswired, potentially contributing to disorders such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

They say findings from their study, published online today in Neuron, may increase the understanding of underlying causes of ADHD, potentially facilitating the development of more individualized treatment strategies.

The scientists looked at dopaminergic neurons, which regulate pleasure, motivation, reward, and cognition, and have been implicated in development of ADHD.

They uncovered a receptor system that is critical, during embryonic development, for correct wiring of the dopaminergic brain area. But they also discovered that after brain maturation, a cut in the same receptor, SorCS2, produces a two-chain receptor that induces cell death following damage to the peripheral nervous system.

The researchers report that the SorCS2 receptor functions as a molecular switch between apparently opposing effects in proBDNF. ProBDNF is a neuronal growth factor that helps select cells that are most beneficial to the nervous system, while eliminating those that are less favorable in order to create a finely tuned neuronal network.

They found that some cells in mice deficient in SorCS2 are unresponsive to proBDNF and have dysfunctional contacts between dopaminergic neurons.

"This miswiring of dopaminergic neurons in mice results in hyperactivity and attention deficits," says the study's senior investigator, Anders Nykjaer, M.D., Ph.D., a neuroscientist at Mayo Clinic in Florida and at Aarhus University in Denmark.

"A number of studies have reported that ADHD patients commonly exhibit miswiring in this brain area, accompanied by altered dopaminergic function. We may now have an explanation as to why ADHD risk genes have been linked to regulation of neuronal growth," he says.

"SorCS2 is produced as a single-chain protein — one long row of amino acids — but it can be cut into two chains to perform a different function. While the single-chain receptor is essential to tell the neuron that it is time to stop growing, the two-chain form tells cells that support neurons in the developing peripheral nervous system to die when they should," says Dr. Nykjaer.

Unfortunately, if damage occurs to a nerve in the peripheral nervous system, these cells that wrap around and nourish the neurons will die, preventing efficient regeneration, he says. "Our finding suggests that it may be possible to develop drug therapy to prevent this deadly cut of SorCS2 and treat acute nerve injury," Dr. Nykjaer says.

INFORMATION:

Other Danish and German researchers contributed to the research. The study was funded by the Lundbeck Foundation and the Danish Medical Research Council.

About Mayo Clinic

Recognizing 150 years of serving humanity in 2014, Mayo Clinic is a nonprofit worldwide leader in medical care, research and education for people from all walks of life. For more information, visit 150years.mayoclinic.org, MayoClinic.org or newsnetwork.mayoclinic.org.

Mayo Clinic researchers decode how the brain miswires, possibly causing ADHD

2014-06-04

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

GW Cancer Institute conducts survey on moving toward quality patient-centered care

2014-06-04

WASHINGTON (June 4, 2014) — In order to meet new cancer program accreditation standards, institutions have placed new focus on patient navigation, psychosocial distress screening, and survivorship care plans. Recently published research by the George Washington University (GW) Cancer Institute found these new programs are experiencing "growing pains." The results of a nationwide survey conducted by the GW Cancer Institute and reviewed in the Journal of Oncology Navigation and Survivorship, found that health care professionals could most benefit from greater evaluation of ...

Hemorrhagic fevers can be caused by body's antiviral interferon response

2014-06-04

LA JOLLA, CA—June 4, 2014— Hemorrhagic fevers caused by Lassa, dengue and other viruses affect more than one million people annually and are often fatal, yet scientists have never understood why only some virus-infected people come down with the disease and others do not.

But now, virologists and immunologists at The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) have found a major clue to the mystery of "hemorrhagic fever" syndromes. In findings reported this week in an Early Edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the team showed that Interferon Type I (IFN-I) ...

Astronomers discover first Thorne-Zytkow object, a bizarre type of hybrid star

2014-06-04

In a discovery decades in the making, scientists have detected the first of a "theoretical" class of stars first proposed in 1975 by physicist Kip Thorne and astronomer Anna Żytkow. Thorne-Żytkow objects (TŻOs) are hybrids of red supergiant and neutron stars that superficially resemble normal red supergiants, such as Betelguese in the constellation Orion. They differ, however, in their distinct chemical signatures that result from unique activity in their stellar interiors.

TŻOs are thought to be formed by the interaction of two massive stars―a ...

How red tide knocks out its competition

2014-06-04

New research reveals how the algae behind red tide thoroughly disables – but doesn't kill – other species of algae. The study shows how chemical signaling between algae can trigger big changes in the marine ecosystem.

Marine algae fight other species of algae for nutrients and light, and, ultimately, survival. The algae that cause red tides, the algal blooms that color blue ocean waters red, carry an arsenal of molecules that disable some other algae. The incapacitated algae don't necessarily die, but their growth grinds to a halt. This could explain part of why blooms ...

New diagnostic imaging techniques deemed safe in simulations

2014-06-04

DURHAM, N.C. -- Gamma and neutron imaging offer possible improvements over existing techniques such as X-ray or CT, but their safety is not yet fully understood. Using computer simulations, imaging the liver and breast with gamma or neutron radiation was found to be safe, delivering levels of radiation on par with conventional medical imaging, according to researchers at Duke Medicine.

The findings, published in the June issue of the journal Medical Physics, will help researchers to move testing of gamma and neutron imaging into animals and later humans.

Conventional ...

Study: When hospital workers get vaccines, community flu rates fall

2014-06-04

Anaheim, Calif., June 4, 2014 – For every 15 healthcare providers who receive the influenza vaccination, one fewer person in the community will contract an influenza-like illness, according to a study using California public health data from 2009 – 2012.

In an abstract that will be presented on June 7 at the 41st Annual Conference of the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC), a researcher analyzed archival data from the California Department of Public Health to determine the relationship between vaccinating healthcare personnel against ...

MU scientists successfully transplant, grow stem cells in pigs

2014-06-04

COLUMBIA, Mo. – One of the biggest challenges for medical researchers studying the effectiveness of stem cell therapies is that transplants or grafts of cells are often rejected by the hosts. This rejection can render experiments useless, making research into potentially life-saving treatments a long and difficult process. Now, researchers at the University of Missouri have shown that a new line of genetically modified pigs will host transplanted cells without the risk of rejection.

"The rejection of transplants and grafts by host bodies is a huge hurdle for medical researchers," ...

Saturated fat intake may influence a person's expression of genetic obesity risk

2014-06-04

Boston, MA (June 4, 2014) ─ Limiting saturated fat could help people whose genetic make-up increases their chance of being obese. In a new study, researchers from the Jean Mayer USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging (USDA HNRCA) at Tufts University identified 63 gene variants related to obesity and used them to calculate a genetic risk score for obesity for more than 2,800 white, American men and women enrolled in two large studies on heart disease prevention. People with a higher genetic risk score, who also consumed more of their calories as saturated fat, ...

Ice cream sensations on the computer

2014-06-04

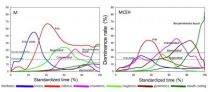

Changes in coldness, creaminess or texture that we experience in the mouth while we are eating an ice cream can be visualised on a screen using coloured curves. Graphs help manufacturers improve product quality, as proven by researchers at the Institute of Agrochemistry and Food Technology in Valencia, Spain.

In the last five years a technique known as 'Temporal Dominance of Sensations' (TDS) has become popular, used to analyse how consumer impressions evolve from the moment they taste a product.

Researchers at the Institute of Agrochemistry and Food Technology (CSIC) ...

Weight loss surgery also safeguards obese people against cancer

2014-06-04

Weight loss surgery might have more value than simply helping morbidly obese people to shed unhealthy extra pounds. It reduces their risk of cancer to rates almost similar to those of people of normal weight. This is the conclusion of the first comprehensive review article taking into account relevant studies about obesity, cancer rates and a weight loss procedure called bariatric surgery. Published in Springer's journal Obesity Surgery, the review was led by Daniela Casagrande of the Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul in Brazil.

With bariatric surgery, a part ...