(Press-News.org) Harvard Stem Cell Institute scientists at Boston Children's Hospital have new evidence in mice that it may be possible to repair a chronically diseased liver by forcing mature liver cells to revert back to a stem cell-like state.

The researchers, led by Fernando Camargo, PhD, happened upon this discovery while investigating whether a biochemical cascade called Hippo, which controls how big the liver grows, also affects cell fate. The unexpected answer, published in the journal Cell, is that switching off the Hippo-signaling pathway in mature liver cells generates very high rates of dedifferentiation. This means the cells turn back the clock to become stem-cell like again, thus allowing them to give rise to functional progenitor cells that can regenerate a diseased liver.

The liver has been a model of regeneration for decades, and it's well known that mature liver cells can duplicate in response to injury. Even if three-quarters of a liver is surgically removed, duplication alone could return the organ to its normal functioning mass. This new research indicates that there is a second mode of regeneration that may be repairing less radical, but more constant liver damage, and chips away at a long-held theory that there's a pool of stem cells in the liver waiting to be activated.

"I think this study highlights the tremendous plasticity of mature liver cells," said Camargo, who is an associate professor in the Harvard Department of Stem Cell and Regenerative Biology, and based in the Stem Cell Program at Boston Children's Hospital. "It's not that you have a very small population of cells that can be recruited to an injury; almost 80 percent of hepatocytes [liver cells] can undergo this cell fate change."

Much of the work dissecting the biology of these changes and establishing that the dedifferentated cells are functional progenitors was carried out by the Cell paper's first co-authors Dean Yimlamai, MD, PhD, and Constantina Christodoulou, PhD, of Boston Children's Hospital.

The next step, Camargo said, would be to figure out how Hippo's activity changes in cells affected by chronic liver injury or diseases such as hepatitis. In the long term, this work could lead to drugs that manipulate the Hippo activity of mature liver cells inside of patients to spur dedifferentiation and hasten healing.

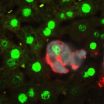

It might also be possible to control Hippo signaling to grow countless liver progenitor cells in a laboratory dish for transplant, which Camargo's team pursued in the Cell paper using mice born with a genetic liver disease. They cultured healthy liver progenitor cells and transplanted them into the diseased mice. Over a period of three or four months, the transplanted liver cells engrafted and the animals saw improvement of their condition.

"People have been trying to use liver cell transplants for metabolic diseases since the early 90s, but because of the source of cells—discarded livers—they were unsuccessful," Camargo said. "With this unlimited source of cells from a patient, we think that perhaps it's time to think again about doing hepatocyte or progenitor cell transplants in the context of liver genetic disorders."

The observation that mature liver cells dedifferentiate comes after a number of related studies published in the past year from Harvard researchers showing that mature cells in several different internal organs, including the kidneys, adrenal glands, and lungs, are more plastic than we once assumed.

"I think that maybe it is something that people have overlooked because the field has been so stem cell centric," said Camargo, also a Harvard Stem Cell Institute Principal Faculty member. "But I think the bottom line is that the cells that we have in our body are plastic, and understanding pathways that underlie that plasticity could be another way of potentially manipulating regeneration or expanding some kind of cell type for regenerative medicine."

INFORMATION:

This work was supported by the Harvard Stem Cell Institute, the Stand Up to Cancer-AACR Initiative, the National Institutes of Health, and the Department of Defense.

Cited: Yimlamai et al., Hippo pathway activity influences liver cell fate, Cell (June 5, 2014), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.060

A new model of liver regeneration

Harvard researchers find switch that causes mature liver cells to revert back to stem cell-like state

2014-06-05

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Vanderbilt scientists discover that chemical element bromine is essential to human life

2014-06-05

Twenty-seven chemical elements are considered to be essential for human life.

Now there is a 28th – bromine.

In a paper published Thursday by the journal Cell, Vanderbilt University researchers establish for the first time that bromine, among the 92 naturally-occurring chemical elements in the universe, is the 28th element essential for tissue development in all animals, from primitive sea creatures to humans.

"Without bromine, there are no animals. That's the discovery," said Billy Hudson, Ph.D., the paper's senior author and Elliott V. Newman Professor of Medicine.

The ...

Flowers' polarization patterns help bees find food

2014-06-05

Like many other insect pollinators, bees find their way around by using a polarization sensitive area in their eyes to 'see' skylight polarization patterns. However, while other insects are known to use such sensitivity to identify appropriate habitats, locate suitable sites to lay their eggs and find food, a non-navigation function for polarization vision has never been identified in bees – until now.

Professor Julian Partridge, from Bristol's School of Biological Sciences and the School of Animal Biology at the University of Western Australia, with his Bristol-based ...

Stem cells hold keys to body's plan

2014-06-05

Case Western Reserve researchers have discovered landmarks within pluripotent stem cells that guide how they develop to serve different purposes within the body. This breakthrough offers promise that scientists eventually will be able to direct stem cells in ways that prevent disease or repair damage from injury or illness. The study and its results appear in the June 5 edition of the journal Cell Stem Cell.

Pluripotent stem cells are so named because they can evolve into any of the cell types that exist within the body. Their immense potential captured the attention ...

Couples sleep in sync when the wife is satisfied with their marriage

2014-06-05

DARIEN, IL – A new study suggests that couples are more likely to sleep in sync when the wife is more satisfied with their marriage.

Results show that overall synchrony in sleep-wake schedules among couples was high, as those who slept in the same bed were awake or asleep at the same time about 75 percent of the time. When the wife reported higher marital satisfaction, the percent of time the couple was awake or asleep at the same time was greater.

"Most of what is known about sleep comes from studying it at the individual level; however, for most adults, sleep is a ...

The connection between oxygen and diabetes

2014-06-05

Researchers at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine have, for the first time, described the sequence of early cellular responses to a high-fat diet, one that can result in obesity-induced insulin resistance and diabetes. The findings, published in the June 5 issue of Cell, also suggest potential molecular targets for preventing or reversing the process.

"We've described the etiology of obesity-related diabetes. We've pinpointed the steps, the way the whole thing happens," said Jerrold M. Olefsky, MD, associate dean for Scientific Affairs and Distinguished ...

Investors' risk tolerance decreases with the stock market, MU study finds

2014-06-05

COLUMBIA, Mo — As the U.S. economy slowly recovers many investors remain wary about investing in the stock market. Now, Michael Guillemette, an assistant professor of personal financial planning in the University of Missouri College of Human Environmental Sciences, analyzed investors' "risk tolerance," or willingness to take risks, and found that it decreased as the stock market faltered. Guillemette says this is a very counterproductive behavior for investors who want to maximize their investment returns.

"At its face, it seems fairly obvious that investors would be ...

What a 66-million-year-old forest fire reveals about the last days of the dinosaurs

2014-06-05

This news release is available in French.

As far back as the time of the dinosaurs, 66 million years ago, forests recovered from fires in the same manner they do today, according to a team of researchers from McGill University and the Royal Saskatchewan Museum.

During an expedition in southern Saskatchewan, Canada, the team discovered the first fossil-record evidence of forest fire ecology - the regrowth of plants after a fire - revealing a snapshot of the ecology on earth just before the mass extinction of the dinosaurs. The researchers also found evidence that ...

University of Toronto biologists pave the way for improved epilepsy treatments

2014-06-05

TORONTO, ON – University of Toronto biologists leading an investigation into the cells that regulate proper brain function, have identified and located the key players whose actions contribute to afflictions such as epilepsy and schizophrenia. The discovery is a major step toward developing improved treatments for these and other neurological disorders.

"Neurons in the brain communicate with other neurons through synapses, communication that can either excite or inhibit other neurons," said Professor Melanie Woodin in the Department of Cell and Systems Biology at the ...

Use of gestures reflects language instinct in young children

2014-06-05

Young children instinctively use a "language-like" structure to communicate through gestures, according to research published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science.

The research, led by the University of Warwick, shows that when young children are asked to use gestures to communicate, their gestures segment information and reorganize it into language-like sequences.

This finding suggests that children are not just learning language from older generations — their own preferences in communication may have shaped how languages ...

Overcoming barriers to successful use of autonomous unmanned aircraft

2014-06-05

WASHINGTON -- While civil aviation is on the threshold of potentially revolutionary changes with the emergence of increasingly autonomous unmanned aircraft, these new systems pose serious questions about how they will be safely and efficiently integrated into the existing civil aviation structure, says a new report from the National Research Council. The report identifies key barriers and provides a research agenda to aid the orderly incorporation of unmanned and autonomous aircraft into public airspace.

"There is little doubt that over the long run the potential benefits ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Public and patient involvement in research is a balancing act of power

Scientists discover “bacterial constipation,” a new disease caused by gut-drying bacteria

DGIST identifies “magic blueprint” for converting carbon dioxide into resources through atom-level catalyst design

COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy may help prevent preeclampsia

Menopausal hormone therapy not linked to increased risk of death

Chronic shortage of family doctors in England, reveals BMJ analysis

Booster jabs reduce the risks of COVID-19 deaths, study finds

Screening increases survival rate for stage IV breast cancer by 60%

ACC announces inaugural fellow for the Thad and Gerry Waites Rural Cardiovascular Research Fellowship

University of Oklahoma researchers develop durable hybrid materials for faster radiation detection

Medicaid disenrollment spikes at age 19, study finds

Turning agricultural waste into advanced materials: Review highlights how torrefaction could power a sustainable carbon future

New study warns emerging pollutants in livestock and aquaculture waste may threaten ecosystems and public health

Integrated rice–aquatic farming systems may hold the key to smarter nitrogen use and lower agricultural emissions

Hope for global banana farming in genetic discovery

Mirror image pheromones help beetles swipe right

Prenatal lead exposure related to worse cognitive function in adults

Research alert: Understanding substance use across the full spectrum of sexual identity

Pekingese, Shih Tzu and Staffordshire Bull Terrier among twelve dog breeds at risk of serious breathing condition

Selected dog breeds with most breathing trouble identified in new study

Interplay of class and gender may influence social judgments differently between cultures

Pollen counts can be predicted by machine learning models using meteorological data with more than 80% accuracy even a week ahead, for both grass and birch tree pollen, which could be key in effective

Rewriting our understanding of early hominin dispersal to Eurasia

Rising simultaneous wildfire risk compromises international firefighting efforts

Honey bee "dance floors" can be accurately located with a new method, mapping where in the hive forager bees perform waggle dances to signal the location of pollen and nectar for their nestmates

Exercise and nutritional drinks can reduce the need for care in dementia

Michelson Medical Research Foundation awards $750,000 to rising immunology leaders

SfN announces Early Career Policy Ambassadors Class of 2026

Spiritual practices strongly associated with reduced risk for hazardous alcohol and drug use

Novel vaccine protects against C. diff disease and recurrence

[Press-News.org] A new model of liver regenerationHarvard researchers find switch that causes mature liver cells to revert back to stem cell-like state