(Press-News.org) In laboratory tests, researchers have used electrical stimulation of retinal cells to produce the same patterns of activity that occur when the retina sees a moving object. Although more work remains, this is a step toward restoring natural, high-fidelity vision to blind people, the researchers say. The work was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health.

Just 20 years ago, bionic vision was more a science fiction cliché than a realistic medical goal. But in the past few years, the first artificial vision technology has come on the market in the United States and Western Europe, allowing people who've been blinded by retinitis pigmentosa to regain some of their sight. While remarkable, the technology has its limits. It has enabled people to navigate through a door and even read headline-sized letters, but not to drive, jog down the street, or see a loved one's face.

A team based at Stanford University in California is working to improve the technology by targeting specific cells in the retina—the neural tissue at the back of the eye that converts light into electrical activity.

"We've found that we can reproduce natural patterns of activity in the retina with exquisite precision," said E.J. Chichilnisky, Ph.D., a professor of neurosurgery at Stanford's School of Medicine and Hansen Experimental Physics Laboratory. The study was published in Neuron, and was funded in part by NIH's National Eye Institute (NEI) and National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB).

The retina contains several cell layers. The first layer contains photoreceptor cells, which detect light and convert it into electrical signals. Retinitis pigmentosa and several other blinding diseases are caused by a loss of these cells. The strategy behind many bionic retinas, or retinal prosthetics, is to bypass the need for photoreceptors and stimulate the retinal ganglion cell layer, the last stop in the retina before visual signals are sent to the brain.

Several types of retinal prostheses are under development. The Argus II, which was developed by Second Sight Therapeutics with more than $25 million in support from NEI, is the best known of these devices. In the United States, it was approved for treating retinitis pigmentosa in 2013, and it's now available at a limited number of medical centers throughout the country. It consists of a camera, mounted on a pair of goggles, which transmits wireless signals to a grid of electrodes implanted on the retina. The electrodes stimulate retinal ganglion cells and give the person a rough sense of what the camera sees, including changes in light and contrast, edges, and rough shapes.

"It's very exciting for someone who may not have seen anything for 20-30 years. It's a big deal. On the other hand, it's a long way from natural vision," said Dr. Chichilnisky, who was not involved in development of the Argus II.

Current technology does not have enough specificity or precision to reproduce natural vision, he said. Although much of visual processing occurs within the brain, some processing is accomplished by retinal ganglion cells. There are 1 to 1.5 million retinal ganglion cells inside the retina, in at least 20 varieties. Natural vision –including the ability to see details in shape, color, depth and motion—requires activating the right cells at the right time.

The new study shows that patterned electrical stimulation can do just that in isolated retinal tissue. The lead author was Lauren Jepson, Ph.D., who was a postdoctoral fellow in Dr. Chichilnisky's former lab at the Salk Institute in La Jolla, California. The pair collaborated with researchers at the University of California, San Diego, the Santa Cruz Institute for Particle Physics, and the AGH University of Science and Technology in Krakow, Poland.

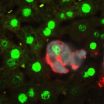

They focused their efforts on a type of retinal ganglion cell called parasol cells. These cells are known to be important for detecting movement, and its direction and speed, within a visual scene. When a moving object passes through visual space, the cells are activated in waves across the retina.

The researchers placed patches of retina on a 61-electrode grid. Then they sent out pulses at each of the electrodes and listened for cells to respond, almost like sonar. This enabled them to identify parasol cells, which have distinct responses from other retinal ganglion cells. It also established the amount of stimulation required to activate each of the cells. Next, the researchers recorded the cells' responses to a simple moving image—a white bar passing over a gray background. Finally, they electrically stimulated the cells in this same pattern, at the required strengths. They were able to reproduce the same waves of parasol cell activity that they observed with the moving image.

"There is a long way to go between these results and making a device that produces meaningful, patterned activity over a large region of the retina in a human patient," Dr. Chichilnisky said. "But if we can handle the many technical hurdles ahead, we may be able to speak to the nervous system in its own language, and precisely reproduce its normal function."

Such advances could help make artificial vision more natural, and could be applied to other types of prosthetic devices, too, such as those being studied to help paralyzed individuals regain movement. NEI supports many other projects geared toward retinal prosthetics.

"Retinal prosthetics hold great promise, but this research is a marathon, not a sprint," said Thomas Greenwell, Ph.D., a program director in retinal neuroscience at NEI. "This important study helps illustrate the challenges of restoring high-quality vision, one group's progress toward that goal, and the continued need to for the entire field to keep innovating."

INFORMATION:

The study was funded by NIH grants EY012171 and EB004410, the National Science Foundation, the McKnight Foundation, the San Diego Foundation Blasker Award, and the Polish government.

For more information about retinitis pigmentosa, visit http://nei.nih.gov/health/pigmentosa/pigmentosa_facts.asp.

Reference:

Jepson LH et al. "High-Fidelity Reproduction of Spatiotemporal Visual Signals for Retinal Prosthesis." Neuron, June 2014. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.04.044

NEI leads the federal government's research on the visual system and eye diseases. NEI supports basic and clinical science programs that result in the development of sight-saving treatments. For more information, visit http://www.nei.nih.gov.

NIBIB's mission is to improve health by leading the development and accelerating the application of biomedical technologies. The Institute is committed to integrating the physical and engineering sciences with the life sciences to advance basic research and medical care. NIBIB supports emerging technology research and development within its internal laboratories and through grants, collaborations, and training. More information is available at the NIBIB website: http://www.nibib.nih.gov.

About the National Institutes of Health (NIH): NIH, the nation's medical research agency, includes 27 Institutes and Centers and is a component of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. NIH is the primary federal agency conducting and supporting basic, clinical, and translational medical research, and is investigating the causes, treatments, and cures for both common and rare diseases. For more information about NIH and its programs, visit http://www.nih.gov.

NIH...Turning Discovery Into Health®

Making artificial vision look more natural

NIH-funded study could help improve retinal prosthetic devices

2014-06-05

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Discovered a new way to control genetic material altered in cancer

2014-06-05

When we talk about genetic material, we are usually referring to the DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) that we inherit from our parents. This DNA is the factory where is built a similar molecule called RNA (ribonucleic acid) which produces our proteins, such as hemoglobin or insulin , allowing the lives of our cells. But there is a special group called non-coding RNA that has a more enigmatic function.

The best known is microRNAs, tiny molecules that are responsible for turning on or off our genome like an electrical current switch. Today, an article published in the prestigious ...

A new model of liver regeneration

2014-06-05

Harvard Stem Cell Institute scientists at Boston Children's Hospital have new evidence in mice that it may be possible to repair a chronically diseased liver by forcing mature liver cells to revert back to a stem cell-like state.

The researchers, led by Fernando Camargo, PhD, happened upon this discovery while investigating whether a biochemical cascade called Hippo, which controls how big the liver grows, also affects cell fate. The unexpected answer, published in the journal Cell, is that switching off the Hippo-signaling pathway in mature liver cells generates very ...

Vanderbilt scientists discover that chemical element bromine is essential to human life

2014-06-05

Twenty-seven chemical elements are considered to be essential for human life.

Now there is a 28th – bromine.

In a paper published Thursday by the journal Cell, Vanderbilt University researchers establish for the first time that bromine, among the 92 naturally-occurring chemical elements in the universe, is the 28th element essential for tissue development in all animals, from primitive sea creatures to humans.

"Without bromine, there are no animals. That's the discovery," said Billy Hudson, Ph.D., the paper's senior author and Elliott V. Newman Professor of Medicine.

The ...

Flowers' polarization patterns help bees find food

2014-06-05

Like many other insect pollinators, bees find their way around by using a polarization sensitive area in their eyes to 'see' skylight polarization patterns. However, while other insects are known to use such sensitivity to identify appropriate habitats, locate suitable sites to lay their eggs and find food, a non-navigation function for polarization vision has never been identified in bees – until now.

Professor Julian Partridge, from Bristol's School of Biological Sciences and the School of Animal Biology at the University of Western Australia, with his Bristol-based ...

Stem cells hold keys to body's plan

2014-06-05

Case Western Reserve researchers have discovered landmarks within pluripotent stem cells that guide how they develop to serve different purposes within the body. This breakthrough offers promise that scientists eventually will be able to direct stem cells in ways that prevent disease or repair damage from injury or illness. The study and its results appear in the June 5 edition of the journal Cell Stem Cell.

Pluripotent stem cells are so named because they can evolve into any of the cell types that exist within the body. Their immense potential captured the attention ...

Couples sleep in sync when the wife is satisfied with their marriage

2014-06-05

DARIEN, IL – A new study suggests that couples are more likely to sleep in sync when the wife is more satisfied with their marriage.

Results show that overall synchrony in sleep-wake schedules among couples was high, as those who slept in the same bed were awake or asleep at the same time about 75 percent of the time. When the wife reported higher marital satisfaction, the percent of time the couple was awake or asleep at the same time was greater.

"Most of what is known about sleep comes from studying it at the individual level; however, for most adults, sleep is a ...

The connection between oxygen and diabetes

2014-06-05

Researchers at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine have, for the first time, described the sequence of early cellular responses to a high-fat diet, one that can result in obesity-induced insulin resistance and diabetes. The findings, published in the June 5 issue of Cell, also suggest potential molecular targets for preventing or reversing the process.

"We've described the etiology of obesity-related diabetes. We've pinpointed the steps, the way the whole thing happens," said Jerrold M. Olefsky, MD, associate dean for Scientific Affairs and Distinguished ...

Investors' risk tolerance decreases with the stock market, MU study finds

2014-06-05

COLUMBIA, Mo — As the U.S. economy slowly recovers many investors remain wary about investing in the stock market. Now, Michael Guillemette, an assistant professor of personal financial planning in the University of Missouri College of Human Environmental Sciences, analyzed investors' "risk tolerance," or willingness to take risks, and found that it decreased as the stock market faltered. Guillemette says this is a very counterproductive behavior for investors who want to maximize their investment returns.

"At its face, it seems fairly obvious that investors would be ...

What a 66-million-year-old forest fire reveals about the last days of the dinosaurs

2014-06-05

This news release is available in French.

As far back as the time of the dinosaurs, 66 million years ago, forests recovered from fires in the same manner they do today, according to a team of researchers from McGill University and the Royal Saskatchewan Museum.

During an expedition in southern Saskatchewan, Canada, the team discovered the first fossil-record evidence of forest fire ecology - the regrowth of plants after a fire - revealing a snapshot of the ecology on earth just before the mass extinction of the dinosaurs. The researchers also found evidence that ...

University of Toronto biologists pave the way for improved epilepsy treatments

2014-06-05

TORONTO, ON – University of Toronto biologists leading an investigation into the cells that regulate proper brain function, have identified and located the key players whose actions contribute to afflictions such as epilepsy and schizophrenia. The discovery is a major step toward developing improved treatments for these and other neurological disorders.

"Neurons in the brain communicate with other neurons through synapses, communication that can either excite or inhibit other neurons," said Professor Melanie Woodin in the Department of Cell and Systems Biology at the ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Afraid of chemistry at school? It’s not all the subject’s fault

How tech-dependency and pandemic isolation have created ‘anxious generation’

Nearly three quarters of US baby foods are ultra-processed, new study finds

Nonablative radiofrequency may improve sexual function in postmenopausal women

Pulsed dynamic water electrolysis: Mass transfer enhancement, microenvironment regulation, and hydrogen production optimization

Coordination thermodynamic control of magnetic domain configuration evolution toward low‑frequency electromagnetic attenuation

High‑density 1D ionic wire arrays for osmotic energy conversion

DAYU3D: A modern code for HTGR thermal-hydraulic design and accident analysis

Accelerating development of new energy system with “substance-energy network” as foundation

Recombinant lipidated receptor-binding domain for mucosal vaccine

Rising CO₂ and warming jointly limit phosphorus availability in rice soils

Shandong Agricultural University researchers redefine green revolution genes to boost wheat yield potential

Phylogenomics Insights: Worldwide phylogeny and integrative taxonomy of Clematis

Noise pollution is affecting birds' reproduction, stress levels and more. The good news is we can fix it.

Researchers identify cleaner ways to burn biomass using new environmental impact metric

Avian malaria widespread across Hawaiʻi bird communities, new UH study finds

New study improves accuracy in tracking ammonia pollution sources

Scientists turn agricultural waste into powerful material that removes excess nutrients from water

Tracking whether California’s criminal courts deliver racial justice

Aerobic exercise may be most effective for relieving depression/anxiety symptoms

School restrictive smartphone policies may save a small amount of money by reducing staff costs

UCLA report reveals a significant global palliative care gap among children

The psychology of self-driving cars: Why the technology doesn’t suit human brains

Scientists discover new DNA-binding proteins from extreme environments that could improve disease diagnosis

Rapid response launched to tackle new yellow rust strains threatening UK wheat

How many times will we fall passionately in love? New Kinsey Institute study offers first-ever answer

Bridging eye disease care with addiction services

Study finds declining perception of safety of COVID-19, flu, and MMR vaccines

The genetics of anxiety: Landmark study highlights risk and resilience

How UCLA scientists helped reimagine a forgotten battery design from Thomas Edison

[Press-News.org] Making artificial vision look more naturalNIH-funded study could help improve retinal prosthetic devices