(Press-News.org) With Father's Day approaching, SF State's Jeff Cookston has some advice for creating better harmony with dad. In a recent study, he found that when an adolescent is having an argument with their father and seeks out others for help, the response he or she receives is linked to better well-being and father-child relationships.

Adolescents who receive an reason for the father's behavior or a better understanding of who is at fault feel better about themselves and about dad as well. Those feelings about dad, in turn, are linked to a lower risk of depression for youth.

The study is the first to explore the intricacies of what Cookston, a professor and chair of the psychology department who has done extensive studies on fatherhood, calls "guided cognitive reframing." Previous research looked at who adolescents sought out for reframing and why; this study takes that research a step further. "There has been a lot of evidence suggesting that talking to people about conflict is a good thing for adolescents," he said. "What we did for the first time was look at what actually happens when they talk to someone."

Cookston and his colleagues surveyed 392 families about adolescents' conflicts with their co-resident fathers and stepfathers. Parents and children were asked who was sought out for support and how frequently; how often those individuals explained the fathers' behavior or blamed the fathers for the conflict; and how the adolescents felt about themselves and their fathers after the reframing.

Mothers were the most sought-out source for reframing, followed by a non-parental figure -- a friend, for example, or a non-parental family member. Next were biological fathers and, lastly, stepfathers. But how often adolescents seek out a specific source for support does not have an impact on their well-being, the study showed. Instead, it is the quality of the reframing -- whether an explanation is provided for dad's behavior or whether responsibility for the conflict is assigned -- that drives how they feel following the conversation.

"When kids get explanations and good reasons that fit with the world they see, it helps them feel better," Cookston said. "It's sometimes hard to change how adolescents feel about situations, but we can talk to them about how they think about those situations."

Half the families surveyed consisted of co-resident biological fathers and half were co-resident stepfathers. In addition, the survey group was split between families of European descent and families of Mexican descent. But despite those variations in the families, the results were overwhelmingly similar.

The study highlights the value of helping adolescents understand conflict, their role in the family and their relationships, according to Cookston. "Adolescence is a time of physiological changes in the brain and in the way a child sees and interprets the world. We can use this time to help them understand personal relationships the same way we expect them to learn and understand, for example, geometry or algebra," he said. "Families are happier when they have less negative emotions, so anything we can do to promote more positive or even more neutral emotions within family is desirable."

Cookston has conducted wide-ranging research on parenting and fatherhood, with a focus on how children from diverse backgrounds respond to parenting, and how children perceive and construct relationships with fathers. His research has shown that the relationship between father and child can have a significant impact on the child's tendencies toward depression and behavior problems.

"He said what? Guided cognitive reframing about the co-resident father/stepfather–adolescent relationship," by Jeff Cookston, Andres Olide, Ross D. Parke, William V. Fabricius, Delia S. Saenz and Sanford L. Braver, was published in the March issue of the Journal of Research on Adolescence.

INFORMATION:

Argument with dad? Find friendly ears to talk it out, study shows

2014-06-06

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Scientists reveal details of calcium 'safety-valve' in cells

2014-06-06

UPTON, NY -- Sometimes a cell has to die-when it's done with its job or inflicted with injury that could otherwise harm an organism. Conversely, cells that refuse to die when expected can lead to cancer. So scientists interested in fighting cancer have been keenly interested in learning the details of "programmed cell death." They want to understand what happens when this process goes awry and identify new targets for anticancer drugs.

The details of one such target have just been identified by a group of scientists from the U.S. Department of Energy's Brookhaven National ...

Brain traffic jams that can disappear in 30 seconds

2014-06-06

BUFFALO, N.Y. – Motorists in Los Angeles, San Francisco and other gridlocked cities could learn something from the fruit fly.

Scientists have found that cellular blockages, the molecular equivalent to traffic jams, in nerve cells of the insect's brain can form and dissolve in 30 seconds or less.

The findings, presented in the journal PLOS ONE, could provide scientists much-needed clues to better identify and treat neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's and Huntington's.

"Our research suggests that fixed, permanent blocks may impede the transport of important ...

LSU biologist John Caprio, Japanese colleagues identify unique way catfish locate prey

2014-06-06

BATON ROUGE – Animals incorporate a number of unique methods for detecting prey, but for the Japanese sea catfish, Plotosus japonicus, it is especially tricky given the dark murky waters where it resides.

John Caprio, George C. Kent Professor of Biological Sciences at LSU, and colleagues from Kagoshima University in Japan have identified that these fish are equipped with sensors that can locate prey by detecting slight changes in the water's pH level.

A paper, "Marine teleost locates live prey through pH sensing," detailing the work of Caprio and his research partners, ...

Better tissue healing with disappearing hydrogels

2014-06-06

When stem cells are used to regenerate bone tissue, many wind up migrating away from the repair site, which disrupts the healing process. But a technique employed by a University of Rochester research team keeps the stem cells in place, resulting in faster and better tissue regeneration. The key, as explained in a paper published in Acta Biomaterialia, is encasing the stem cells in polymers that attract water and disappear when their work is done.

The technique is similar to what has already been used to repair other types of tissue, including cartilage, but had never ...

Lower asthma risk is associated with microbes in infants' homes

2014-06-06

Infants exposed to a diverse range of bacterial species in house dust during the first year of life appear to be less likely to develop asthma in early childhood, according to a new study published online on June 6, 2014, in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology.

Children who were neither allergic nor prone to wheezing as three-year-olds were the most likely to have been exposed to high levels of bacteria, and paradoxically, to high levels of common allergens.

In fact, some of the protective bacteria are abundant in cockroaches and mice, the source of these ...

NASA and NOAA satellites eyeing Mexico's tropical soaker for development

2014-06-06

NASA and NOAA satellites are gathering visible, infrared, microwave and radar data on a persistent tropical low pressure area in the southwestern Bay of Campeche. System 90L now has a 50 percent chance for development, according to the National Hurricane Center and continues to drop large amounts of rainfall over southeastern Mexico.

The Atmospheric Infrared Sounder (AIRS) instrument aboard NASA's Aqua satellite gathered infrared data on the developing low on June 5 at 18:59 UTC (2:59 p.m. EDT).

Basically, AIRS looks at the infrared region of the spectrum. In a spectrum, ...

Study shows health policy researchers lack confidence in social media for communication

2014-06-06

Philadelphia – Though Twitter boats 645 million users across the world, only 14 percent of health policy researchers reported using Twitter – and approximately 20 percent used blogs and Facebook – to communicate their research findings over the past year, according to a new study from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. In contrast, sixty-five percent used traditional media channels, such as press releases or media interviews. While participants believed that social media can be an effective way to communicate research findings, many lacked ...

Evolution of a bimetallic nanocatalyst

2014-06-06

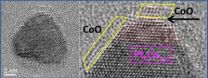

Atomic-scale snapshots of a bimetallic nanoparticle catalyst in action have provided insights that could help improve the industrial process by which fuels and chemicals are synthesized from natural gas, coal or plant biomass. A multi-national lab collaboration led by researchers with the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE)'s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) has taken the most detailed look ever at the evolution of platinum/cobalt bimetallic nanoparticles during reactions in oxygen and hydrogen gases.

"Using in situ aberration-corrected transmission electron ...

Tougher penalties credited for fewer casualties among young male drivers

2014-06-06

VIDEO:

A new Western University study led by Dr. Evelyn Vingilis has found a significant decline in speeding-related fatalities and injuries among young men in Ontario since the province's tough extreme...

Click here for more information.

A new study out of Western University (London, Canada) has found a significant decline in speeding-related fatalities and injuries among young men in Ontario since the province's tough extreme speeding and aggressive driving laws were introduced ...

Endoscope with an oxygen sensor detects pancreatic cancer

2014-06-06

JACKSONVILLE, Fla. — June 6, 3014 — An optical blood oxygen sensor attached to an endoscope is able to identify pancreatic cancer in patients via a simple lendoscopic procedure, according to researchers at Mayo Clinic in Florida.

The study, published in GIE: Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, shows that the device, which acts like the well-known clothespin-type finger clip used to measure blood oxygen in patients, has a sensitivity of 92 percent and a specificity of 86 percent.

MULTIMEDIA ALERT: Video and audio are available for download on the Mayo Clinic News Network.

That ...