(Press-News.org) A new study in The Journal of Experimental Medicine reveals that a high-risk group of patients with follicular lymphoma could benefit from a novel drug combination.

Follicular lymphoma, a B cell lymphoma, is an incurable form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma that is diagnosed each year in 120,000 people worldwide. Follicular lymphoma is characterized by slow and relentless tumor growth with inevitable relapses despite intense chemotherapy. Follicular lymphomas are driven by mutations that activate the BCL2 protein, which prevents cancer cells from dying, but additional genetic changes are also required. These could include mutations resulting in loss of cell cycle control, which is a hallmark of cancer and has a well-established role in aggressive B cell malignancies.

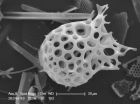

To find out more, Hans-Guido Wendel and colleagues from Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York analyzed genomic data from two large groups of slow-growing follicular lymphomas. The team identified a pattern of linked genetic mutations mainly in genes expressing cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs), which impair the tumor-suppressing retinoblastoma (RB) pathway in nearly 50 percent of follicular lymphomas. The pathogenic role of these mutations was also confirmed in vivo in a mouse model of follicular lymphoma. Increased CDK4 activity is readily measured in tumor samples, and Wendel and colleagues show that a combination therapy of CDK4 and BCL2 inhibitors is safe and effective against available mouse models of follicular lymphoma.

INFORMATION:

Oricchio, E., et al. 2014. J. Exp. Med. doi:10.1084/jem.20132120

About The Journal of Experimental Medicine

The Journal of Experimental Medicine (JEM) is published by The Rockefeller University Press. All editorial decisions on manuscripts submitted are made by active scientists in conjunction with our in-house scientific editors. JEM content is posted to PubMed Central, where it is available to the public for free six months after publication. Authors retain copyright of their published works and third parties may reuse the content for non-commercial purposes under a creative commons license. For more information, please visit http://www.jem.org .

Research reported in the press release was supported by the National Cancer Institute, American Cancer Society, Leukemia Research Foundation, Louis V. Gerstner Foundation, Geoffrey Beene Cancer Center, MSKCC, Starr Cancer Consortium, Lymphoma Research Foundation, Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, and the Translational-Integrative Research Fund.

Combination therapy may help patients with follicular lymphoma

2014-06-09

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

No limits to human effects on clouds

2014-06-09

Understanding how clouds affect the climate has been a difficult proposition. What controls the makeup of the low clouds that cool the atmosphere or the high ones that trap heat underneath? How does human activity change patterns of cloud formation? The research of the Weizmann Institute's Prof. Ilan Koren suggests we may be nudging cloud formation in the direction of added area and height. He and his team have analyzed a unique type of cloud formation; their findings, which appeared recently in Science indicate that in pre-industrial times, there was less cloud cover over ...

UNC researchers pinpoint new role for enzyme in DNA repair, kidney cancer

2014-06-09

CHAPEL HILL, N.C. – Twelve years ago, UNC School of Medicine researcher Brian Strahl, PhD, found that a protein called Set2 plays a role in how yeast genes are expressed – specifically how DNA gets transcribed into messenger RNA. Now his lab has found that Set2 is also a major player in DNA repair, a complicated and crucial process that can lead to the development of cancer cells if the repair goes wrong.

"We found that if Set2 is mutated, DNA repair does not properly occur" said Strahl, a professor of biochemistry and biophysics. "One consequence could be that if you ...

Did violence shape our faces?

2014-06-09

(Salt Lake City) —What contributed to the evolution of faces in the ape-like ancestors of humans?

The prehistoric version of a bar fight —over women, resources and other slug-worthy disagreements, new research from the University of Utah scheduled for publication in the journal Biological Reviews on June 9 suggests.

University of Utah biologist David Carrier and Michael H. Morgan, a University of Utah physician, contend that human faces —especially those of our australopith ancestors — evolved to minimize injury from punches to the face during fights between males. ...

Iron supplements improve anemia, quality of life for women with heavy periods

2014-06-09

A study by researchers from Finland found that diagnosis and treatment of anemia is important to improve quality of life among women with heavy periods. Findings published in Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, a journal of the Nordic Federation of Societies of Obstetrics and Gynecology, suggest clinicians screen for anemia and recommend iron supplementation to women with heavy menstrual bleeding (menorrhagia).

One of the common causes of iron deficiency and anemia is heavy bleeding during menstration. Over time monthly mentrual iron loss without adequate ...

Most breast cancer patients may not be getting enough exercise

2014-06-09

Physical activity after breast cancer diagnosis has been linked with prolonged survival and improved quality of life, but most participants in a large breast cancer study did not meet national physical activity guidelines after they were diagnosed. Moreover, African-American women were less likely to meet the guidelines than white women. Published early online in CANCER, a peer-reviewed journal of the American Cancer Society, the findings indicate that efforts to promote physical activity in breast cancer patients may need to be significantly enhanced.

The US Department ...

Longer telomeres linked to risk of brain cancer

2014-06-08

New genomic research led by UC San Francisco (UCSF) scientists reveals that two common gene variants that lead to longer telomeres, the caps on chromosome ends thought by many scientists to confer health by protecting cells from aging, also significantly increase the risk of developing the deadly brain cancers known as gliomas.

The genetic variants, in two telomere-related genes known as TERT and TERC, are respectively carried by 51 percent and 72 percent of the general population. Because it is somewhat unusual for such risk-conferring variants to be carried by a majority ...

New molecule enables quick drug monitoring

2014-06-08

Monitoring the drug concentration in patients is critical for effective treatment, especially in cases of cancer, heart disease, epilepsy and immunosuppression after organ transplants. However, current methods are expensive, time-consuming, and require dedicated personnel and infrastructure away from the patient. Publishing in Nature Chemical Biology, scientists at EPFL introduce novel light-emitting sensor proteins that can quickly and simply show how much drug is in a patient's bloodstream by changing the color of their light. The method is so simple that it could be ...

Retracing early cultivation steps: Lessons from comparing citrus genomes

2014-06-08

Citrus is the world's most widely cultivated fruit crop. In the U.S. alone, the citrus crop was valued at over $3.1 billion in 2013. Originally domesticated in Southeast Asia thousands of years ago before spreading throughout Asia, Europe, and the Americas via trade, citrus is now under attack from citrus greening, an insidious emerging infectious disease that is destroying entire orchards. To help defend citrus against this disease and other threats, researchers worldwide are mobilizing to apply genomic tools and approaches to understand how citrus varieties arose and ...

Warming climates intensify greenhouse gas given out by oceans

2014-06-08

Rising global temperatures could increase the amount of carbon dioxide naturally released by the world's oceans, fuelling further climate change, a study suggests.

Fresh insight into how the oceans can affect CO2 levels in the atmosphere shows that rising temperatures can indirectly increase the amount of the greenhouse gas emitted by the oceans.

Scientists studied a 26,000-year-old sediment core taken from the Gulf of California to find out how the ocean's ability to take up atmospheric CO2 has changed over time.

They tracked the abundance of the key elements silicon ...

Study reveals rats show regret, a cognitive behavior once thought to be uniquely human

2014-06-08

New research from the Department of Neuroscience at the University of Minnesota reveals that rats show regret, a cognitive behavior once thought to be uniquely and fundamentally human.

Research findings were recently published in Nature Neuroscience.

To measure the cognitive behavior of regret, A. David Redish, Ph.D., a professor of neuroscience in the University of Minnesota Department of Neuroscience, and Adam Steiner, a graduate student in the Graduate Program in Neuroscience, who led the study, started from the definitions of regret that economists and psychologists ...