The work was reported in the November 19, 2010, issue of the journal Science.

In the new study, whose authors included collaborators from Weill Cornell Medical College, Receptos, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, the scientists solved the structure of the dopamine D3 receptor (D3R), one of five distinct dopamine receptor subtypes.

"The structure is helping us understand the unique features of the dopamine receptor subfamily, particularly D2 versus D3 specificity," said Scripps Research Professor Raymond C. Stevens, Ph.D., the senior author on this study. "This was previously impossible to appreciate and is very important for dopamine related research."

"The combination of crucial advances in sample preparation and crystallographic techniques led to the determination of the structure of the human dopamine D3 receptor," said Jean Chin, Ph.D., of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), who oversees Stevens' awards, which were supported by the NIH Common Fund and Protein Structure Initiative. "The structure will speed the search for new drugs that target the receptor, an important mediator of behavioral and cognitive functions in humans."

An Intriguing Class of Molecules

This is the fourth structure in a class of molecules known as G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) that the Scripps Research team has solved. This effort, part of the GPCR Network, has been given a boost by a recent grant of more than $16 million from the National Institutes of Health as part of the PSI:Biology Initiative.

About 1,000 GPCRs transmit signals from the outside of human cells to the inside, triggering a response that changes cell activity. Up to half of currently marketed drugs are designed to target these receptors, yet sometimes they cause side effects or are less effective than they could be because the agents do not bind tightly to the receptor.

"Our long-range goal is to develop a better understanding of the structure-function relationship in GPCRs and gain new biological insight," said Stevens. "Ultimately enough structures will be determined together with complementary biochemical data to provide a fine sampling of the various GPCR sequence families and, thus, enable reliable modeling and predictive docking studies of other close family members."

It took Stevens and his colleagues more than 17 years to solve the structure of the first GPCR – the "fight or flight" ß2-adrenergic receptor – and publish it in 2007, and his robust platform for studying the structure and function of these receptors led recently to relatively rapid discovery of other key GPCRs found on different branches of the GPCR family tree. Stevens and his colleagues published the structure of the A2A adenosine receptor involved in pain, heart function, and breathing in 2008, and the CXCR4 receptor that helps regulate immune cells in October 2010.

By knowing the structure and function of GPCRs, researchers will be able to understand precisely how these receptors bind to their "ligands" – be they neurotransmitters, hormones, odors, or even light - and how this coupling activates or inhibits critical signaling pathways, says Stevens.

"These new structures will have an enormous impact on furthering our understanding of GPCR biology and should help improve success rates in drug discovery," he said.

A Three-Year Effort

The effort to solve D3R was the result of three years of research, with tremendous cooperation among groups such as the receptor expression and stabilization team led by first author Scripps Research Scientific Associate Ellen Chien, Ph.D. who led the study, crystallization by Scripps Research Scientific Associate Wei Liu, Ph.D., and the structure analysis conducted in collaboration with Columbia University Professor Jonathan Javitch, M.D., Ph.D., and his East Coast colleagues

"D3R is perhaps the most unstable of all of the receptor structures we have solved in terms of how the receptor behaves in the test tube," Stevens noted. "We believe there are lipid or other small molecules that may have an influence on the receptor that we currently do not understand. Why D3R is so unstable in the test tube is currently an area of investigation."

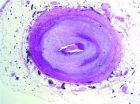

The study shows D3R bound to eticlopride, an experimental compound used in dopamine receptor research. In the laboratory, eticlopride also binds to another dopamine receptor, D2R. By solving the structure of D3R, Stevens says investigators can create a model of D2R since they are so similar to each other and only have a few minor differences.

Yet drugs that bind to both D2R and D3R – such as those to treat schizophrenia – produce multiple side effects that limit their effectiveness. "The structure will also help to define how to make selective dopamine receptor drugs," Stevens said.

Now that the researchers have a representative structure of the dopamine receptor, they plan to move on to solving other receptor subfamilies, such as opioid or serotonin receptors.

### In addition to Stevens, Chien, Liu, and Javitch, authors of the paper, "Structural basis of pharmacological specificity between dopamine D2 and D3 G protein-coupled receptors," include: Qiang Zhao, Gye Won Han, and Vadim Cherezov from The Scripps Research Institute; Michael A. Hanson from Receptos; Vsevolod Katritch from the University of California, San Diego; Lei Shi from Weill Cornell Medical College; and Amy Hauck Newman from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Common Fund, NIH National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) PSI:Biology, and Pfizer, Inc.

About The Scripps Research Institute

The Scripps Research Institute is one of the world's largest independent, non-profit biomedical research organizations at the forefront of basic biomedical science that seeks to comprehend the most fundamental processes of life. Scripps Research is internationally recognized for its discoveries in immunology, molecular and cellular biology, chemistry, neurosciences, autoimmune, cardiovascular, and infectious diseases, and synthetic vaccine development. An institution that evolved from the Scripps Metabolic Clinic founded by philanthropist Ellen Browning Scripps in 1924, Scripps Research currently employs approximately 3,000 scientists, postdoctoral fellows, scientific and other technicians, doctoral degree graduate students, and administrative and technical support personnel. Headquartered in La Jolla, California, the institute also includes Scripps Florida, whose researchers focus on basic biomedical science, drug discovery, and technology development. Scripps Florida is located in Jupiter, Florida. For more information, see www.scripps.edu.

END