(Press-News.org) PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Nanopores may one day lead a revolution in DNA sequencing. By sliding DNA molecules one at a time through tiny holes in a thin membrane, it may be possible to decode long stretches of DNA at lightning speeds. Scientists, however, haven't quite figured out the physics of how polymer strands like DNA interact with nanopores. Now, with the help of a particular type of virus, researchers from Brown University have shed new light on this nanoscale physics.

"What got us interested in this was that everybody in the field studied DNA and developed models for how they interact with nanopores," said Derek Stein, associate professor of physics and engineering at Brown who directed the research. "But even the most basic things you would hope models would predict starting from the basic properties of DNA — you couldn't do it. The only way to break out of that rut was to study something different."

The findings, published today in Nature Communications, might not only help in the development of nanopore devices for DNA sequencing, they could also lead to a new way of detecting dangerous pathogens.

Straightening out the physics

The concept behind nanopore sequencing is fairly simple. A hole just a few billionths of a meter wide is poked in a membrane separating two pools of salty water. An electric current is applied to the system, which occasionally snares a charged DNA strand and whips it through the pore — a phenomenon called translocation. When a molecule translocates, it causes detectable variations in the electric current across the pore. By looking carefully at those variations in current, scientists may be able to distinguish individual nucleotides — the A's, C's, G's and T's coded in DNA molecules.

The first commercially available nanopore sequencers may only be a few years away, but despite advances in the field, surprisingly little is known about the basic physics involved when polymers interact with nanopores. That's partly because of the complexities involved in studying DNA. In solution, DNA molecules form balls of random squiggles, which make understanding their physical behavior extremely difficult.

For example, the factors governing the speed of DNA translocation aren't well understood. Sometimes molecules zip through a pore quickly; other times they slither more slowly, and nobody completely understands why.

One possible explanation is that the squiggly configuration of DNA causes each molecule to experience differences in drag as they're pulled through the water toward the pore. "If a molecule is crumpled up next to the pore, it has a shorter distance to travel and experiences less drag," said Angus McMullen, a physics graduate student at Brown and the study's lead author. "But if it's stretched out then it would feel drag along the whole length and that would cause it to go slower."

The drag effect is impossible to isolate experimentally using DNA, but the virus McMullen and his colleagues studied offered a solution.

The researchers looked at fd, a harmless virus that infects e. coli bacteria. Two things make the virus an ideal candidate for study with nanpores. First, fd viruses are all identical clones of each other. Second, unlike squiggly DNA, fd virus is a stiff, rod-like molecule. Because the virus doesn't curl up like DNA does, the effect of drag on each one should be essentially the same every time.

With drag eliminated as a source of variation in translocation speed, the researchers expected that the only source of variation would be the effect of thermal motion. The tiny virus molecules constantly bump up against the water molecules in which they are immersed. A few random thermal kicks from the rear would speed the virus up as it goes through the pore. A few kicks from the front would slow it down.

The experiments showed that while thermal motion explained much of the variation in translocation speed, it didn't explain it all. Much to the researchers' surprise, they found another source of variation that increased when the voltage across the pore was increased.

"We thought that the physics would be crystal clear," said Jay Tang, associate professor of physics and engineering at Brown and one of the study's co-authors. "You have this stiff [virus] with well-defined diameter and size and you would expect a very clear-cut signal. As it turns out, we found some puzzling physics we can only partially explain ourselves."

The researchers can't say for sure what's causing the variation they observed, but they have a few ideas.

"It's been predicted that depending on where [an object] is inside the pore, it might be pulled harder or weaker," McMullen said. "If it's in the center of the pore, it pulls a little bit weaker than if it's right on the edge. That's been predicted, but never experimentally verified. This could be evidence of that happening, but we're still doing follow up work."

Toward a nanopore sequencer and more

A better understanding of translocation speed could improve the accuracy of nanopore sequencing, McMullen says. It would also be helpful in the crucial task of measuring the length of DNA strands. "If you can predict the translocation speed," McMullen said, "then you can easily get the length of the DNA from how long its translocation was."

The research also helped to reveal other aspects of the translocation process that could be useful in designing future devices. The study showed that the electrical current tends to align the viruses head first to the pore, but on occasions when they're not lined up, they tend to bounce around on the edge of the pore until thermal motion aligns them to go through. However, when the voltage was turned too high, the thermal effects were suppressed and the virus became stuck to the membrane. That suggests a sweet spot in voltage where headfirst translocation is most likely.

None of this is observable directly — the system is simply too small to be seen in action. But the researchers could infer what was happening by looking at slight changes in the current across the pore.

"When the viruses miss, they rattle around and we see these little bumps in the current," Stein said. "So with these little bumps, we're starting to get an idea of what the molecule is doing before it slides through. Normally these sensors are blind to anything that's going on until the molecule slides through."

That would have been impossible to observe using DNA. The floppiness of the DNA molecule allows it to go through a pore in a folded configuration even if it's not aligned head-on. But because the virus is stiff, it can't fold to go through. That enabled the researchers to isolate and observe those contact dynamics.

"These viruses are unique," Stein said. "They're like perfect little yardsticks."

In addition to shedding light on basic physics, the work might also have another application. While the fd virus itself is harmless, the bacteria it infects — e. coli — is not. Based on this work, it might be possible to build a nanopore device for detecting the presence of fd, and by proxy, e. coli. Other dangerous viruses — Ebola and Marburg among them — share the same rod-like structure as fd.

"This might be an easy way to detect these viruses," Tang said. "So that's another potential application for this."

INFORMATION:

The work was supported by the National Science Foundation (grants CBET0846505 and PHYS1058375), and the Brown University Institute for Molecular and Nanoscale Innovation. Hendrick W. de Haan, of University of Ontario Institute of Technology, was also an author on the study.

Editors: Brown University has a fiber link television studio available for domestic and international live and taped interviews, and maintains an ISDN line for radio interviews. For more information, call (401) 863-2476.

Researchers use virus to reveal nanopore physics

2014-06-16

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Strokefinder quickly differentiates bleeding strokes from clot-induced strokes

2014-06-16

The results from the initial clinical studies involving the microwave helmet Strokefinder confirm the usefulness of microwaves for rapid and accurate diagnosis of stroke patients. This is shown in a scientific article being published on June 16. Strokefinder enables earlier diagnosis than current methods, which improves the possibility to counteract brain damage.

In the article, researchers from Chalmers University of Technology, Sahlgrenska Academy and Sahlgrenska University Hospital present results from the initial patient studies completed last year. The study included ...

E-cigarettes far less harmful than cigarettes, says researcher at INFORMS Conference

2014-06-16

A London School of Economics researcher examining the public and private dangers of drugs argues against demonizing e-cigarettes in a presentation being given at a conference of the Institute for Operations Research and the Management Sciences (INFORMS). He also calls on public officials to recognize that alcohol causes greater harm than other recreational drugs and more public attention should be paid to controlling its harmful effects.

Lawrence D. Phillips, an emeritus professor at the London School of Economics, will present his research group's findings about the relative ...

Most millennial moms who skip college also skip marriage

2014-06-16

Waiting until marriage to have babies is now "unusual" among less-educated adults close to 30 years old, Johns Hopkins University researchers found.

"Clearly the role of marriage in fertility and family formation is now modest in early adulthood and the lofty place that marriage once held among the markers of adulthood is in serious question," sociologist Andrew J. Cherlin said. "It is now unusual for non-college graduates who have children in their teens and 20s to have all of them within marriage."

Among parents aged 26 to 31 who didn't graduate from college, 74 ...

Regenerating our kidneys

2014-06-16

Doctors and scientists have for years been astonished to observe patients with kidney disease experiencing renal regeneration. The kidney, unlike its neighbor the liver, was universally understood to be a static organ once it had fully developed.

Now a new study conducted by researchers at Sheba Medical Center, Tel Aviv University and Stanford University turns that theory on its head by pinpointing the precise cellular signalling responsible for renal regeneration and exposing the multi-layered nature of kidney growth. The research, in Cell Reports, was conducted by principal ...

WSU researchers develop fuel cells for increased airplane efficiency

2014-06-16

PULLMAN, Wash.–Washington State University researchers have developed the first fuel cell that can directly convert fuels, such as jet fuel or gasoline, to electricity, providing a dramatically more energy-efficient way to create electric power for planes or cars.

Led by Professors Su Ha and M. Grant Norton in the Voiland College of Engineering and Architecture, the researchers have published the results of their work in the May edition of Energy Technology. A second paper on using their fuel cell with gasoline has been accepted for publication in the Journal of Power ...

Sleep quality and duration improve cognition in aging populations

2014-06-16

EUGENE, Ore. -- (June 16, 2014) -- Maybe turning to sleep gadgets -- wristbands, sound therapy and sleep-monitoring smartphone apps -- is a good idea. A new University of Oregon-led study of middle-aged or older people who get six to nine hours of sleep a night think better than those sleeping fewer or more hours.

The study, published in the June issue of the Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, reaffirms numerous small-scale studies in the United States, Western Europe and Japan, but it does so using data compiled across six middle-income nations and involving more than ...

Tugging on the 'malignant' switch

2014-06-16

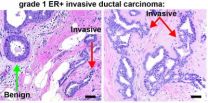

Cambridge, Mass. – June 16, 2014 – A team of researchers led by David J. Mooney, Robert P. Pinkas Family Professor of Bioengineering at the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, have identified a possible mechanism by which normal cells turn malignant in mammary epithelial tissues, the tissues frequently involved in breast cancer.

Dense mammary tissue has long been recognized as a strong indicator of risk for breast cancer. This is why regular breast examinations are considered essential to early detection. Until now, however, the significance of that tissue ...

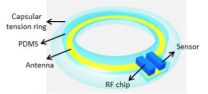

Sensor in eye could track pressure changes, monitor for glaucoma

2014-06-16

Your eye could someday house its own high-tech information center, tracking important changes and letting you know when it's time to see an eye doctor.

University of Washington engineers have designed a low-power sensor that could be placed permanently in a person's eye to track hard-to-measure changes in eye pressure. The sensor would be embedded with an artificial lens during cataract surgery and would detect pressure changes instantaneously, then transmit the data wirelessly using radio frequency waves.

The researchers recently published their results in the Journal ...

LLNL researchers develop high-quality 3-D metal parts using additive manufacturing

2014-06-16

LIVERMORE, Calif. – Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory researchers have developed a new and more efficient approach to a challenging problem in additive manufacturing -- using selective laser melting, namely, the selection of appropriate process parameters that result in parts with desired properties.

Selective laser melting (SLM) is a powder-based, additive manufacturing process where a 3D part is produced, layer by layer, using a high-energy laser beam to fuse the metal powder particles. Some SLM applications require parts that are very dense, with less than ...

Embryonic stem cells offer new treatment for multiple sclerosis

2014-06-16

Scientists in the University of Connecticut's Technology Incubation Program have identified a novel approach to treating multiple sclerosis (MS) using human embryonic stem cells, offering a promising new therapy for more than 2.3 million people suffering from the debilitating disease.

The researchers demonstrated that the embryonic stem cell therapy significantly reduced MS disease severity in animal models and offered better treatment results than stem cells derived from human adult bone marrow.

The study was led by ImStem Biotechnology Inc. of Farmington, Conn., ...