(Press-News.org) COLUMBUS, Ohio – Giving low doses of a particular targeted agent with a cancer-killing virus might improve the effectiveness of the virus as a treatment for cancer, according to a study led by researchers at The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center – Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital and Richard J. Solove Research Institute (OSUCCC – James).

Viruses that are designed to kill cancer cells – oncolytic viruses – have shown promise in clinical trials for the treatment of brain cancer and other solid tumors. This cell and animal study suggests that combining low doses of the drug bortezomib with a particular oncolytic virus might significantly improve the ability of the virus to kill cancer cells during oncolytic virus therapy.

The research is published in the journal Clinical Cancer Research.

"These findings pave the way for a treatment strategy for cancer that combines low doses of bortezomib with an oncolytic virus to maximize the efficacy of the virus with little added toxicity," says principal investigator Balveen Kaur, PhD, professor and vice chair of research, Department of Neurological Surgery and Radiation Oncology, and a member of the OSUCCC – James Translational Therapeutics Program.

"Because bortezomib is already approved by the Food and Drug Administration, a clinical trial could be done relatively quickly to test the effectiveness of the drug-virus combination," Kaur says.

Bortezomib inhibits the activity of proteasomes, structures in cells that break down and recycle proteins. Kaur notes that blocking these "cellular recycling plants" activates a cellular stress response and increases the expression of heat shock proteins. This reaction, which can lead to bortezomib resistance, makes the cells more sensitive to oncolytic virus therapy with little additional toxicity.

For this study, Kaur and her colleagues used a herpes simplex virus-type 1 oncolytic virus. Key technical findings include:

One of the overexpressed heat-shock proteins, HSP90, facilitates oncolytic virus replication, enabling the virus to kill more tumor cells;

In a glioma model, the combination treatment suppressed tumor growth by 92 percent relative to controls and improved survival (six of eight tumors had completely regressed by day 23 after treatment);

Similar outcomes occurred in a head and neck cancer model.

"To our knowledge, this study is the first to show synergy between an oncolytic HSV-1-derived cancer killing virus and bortezomib," Kaur says. "It offers a novel therapeutic strategy that can be rapidly translated in patients with various solid tumors."

INFORMATION:

Funding from the National Institutes of Health (grants NS064607, CA150153, CA163205, NS045758, CA155521) and the Pelotonia Fellowship Program supported this research.

Other researchers involved in this study were Ji Young Yoo, Brian S. Hurwitz, Chelsea Bolyard, Jun-Ge Yu, Jianying Zhang, Karuppaiyah Selvendiran, Kellie S. Rath, Shun He, Deborah S. Parris, Michael A. Caligiuri, Jianhua Yu and Matthew Old, The Ohio State University; David Eaves and Zachary Bailey, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center; Timothy P. Cripe, Nationwide Children's Hospital.

The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center – Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital and Richard J. Solove Research Institute strives to create a cancer-free world by integrating scientific research with excellence in education and patient-centered care, a strategy that leads to better methods of prevention, detection and treatment. Ohio State is one of only 41 National Cancer Institute (NCI)-designated Comprehensive Cancer Centers and one of only four centers funded by the NCI to conduct both phase I and phase II clinical trials. The NCI recently rated Ohio State's cancer program as "exceptional," the highest rating given by NCI survey teams. As the cancer program's 228-bed adult patient-care component, The James is a "Top Hospital" as named by the Leapfrog Group and one of the top cancer hospitals in the nation as ranked by U.S.News & World Report.

Low dose of targeted drug might improve cancer-killing virus therapy

2014-06-16

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

How our brains store recent memories, cell by single cell

2014-06-16

Confirming what neurocomputational theorists have long suspected, researchers at the Dignity Health Barrow Neurological Institute in Phoenix, Ariz. and University of California, San Diego School of Medicine report that the human brain locks down episodic memories in the hippocampus, committing each recollection to a distinct, distributed fraction of individual cells.

The findings, published in the June 16 Early Edition of PNAS, further illuminate the neural basis of human memory and may, ultimately, shed light on new treatments for diseases and conditions that adversely ...

Omega (ω)-3 inhibits blood vessel growth in a model of age-related macular degeneration in vivo

2014-06-16

Boston (June 16, 2014) – Age-related macular degeneration (AMD), which is characterized by choroidal neovascularization (CNV), or blood vessel growth, is the primary cause of blindness in elderly individuals of industrialized countries. The prevalence of the disease is projected to increase 50% by the year 2020. There is an urgent need for new pharmacological interventions for the treatment and prevention of AMD.

Researchers from Massachusetts Eye and Ear/Schepens Eye Research Institute, Harvard Medical School and other institutions have demonstrated for the first time ...

Caterpillars that eat multiple plant species are more susceptible to hungry birds

2014-06-16

Irvine, Calif. — For caterpillars, having a well-rounded diet can be fraught with peril.

UC Irvine and Wesleyan University biologists have learned that caterpillars that feed on one or two plant species are better able to hide from predatory birds than caterpillars that consume a wide variety of plants.

This is probably because the color patterns and hiding behaviors of the caterpillar "specialists" have evolved to allow them to blend into the background flora more effectively than caterpillars that eat many different plant species. Moving among these diverse plant ...

Hunt for extraterrestrial life gets massive methane boost

2014-06-16

A powerful new model to detect life on planets outside of our solar system, more accurately than ever before, has been developed by UCL (University College London) researchers.

The new model focuses on methane, the simplest organic molecule, widely acknowledged to be a sign of potential life.

Researchers from UCL and the University of New South Wales have developed a new spectrum for 'hot' methane which can be used to detect the molecule at temperatures above that of Earth, up to 1,500K/1220°C – something which was not possible before.

To find out what remote planets ...

Physician anesthesiologists identify 5 tests and procedures to avoid

2014-06-16

Proving that less really is more, five specific tests or procedures commonly performed in anesthesiology that may not be necessary and, in some cases should be avoided, will be published online June 16 in JAMA Internal Medicine. The "Top-five" list was created by the American Society of Anesthesiologists® (ASA®) for inclusion in the ABIM Foundation's Choosing Wisely® campaign.

"The Top-five list of activities to question in anesthesiology was developed in an effort to reduce unnecessary, costly procedures and improve patient care," said Onyi Onuoha, M.D., M.P.H., lead ...

Your genes affect your betting behavior

2014-06-16

Investors and gamblers take note: your betting decisions and strategy are determined, in part, by your genes.

University of California, Berkeley, and University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (UIUC) researchers have shown that betting decisions in a simple competitive game are influenced by the specific variants of dopamine-regulating genes in a person's brain.

Dopamine is a neurotransmitter – a chemical released by brain cells to signal other brain cells – that is a key part of the brain's reward and pleasure-seeking system. Dopamine deficiency leads to Parkinson's ...

When genes play games

2014-06-16

Berkeley — What do you get when you mix theorists in computer science with evolutionary biologists? You get an algorithm to explain sex.

It turns out that 155 years after Charles Darwin first published "On the Origin of Species," vexing questions remain about key aspects of evolution, such as how sexual recombination and natural selection produced the teeming diversity of life that exists today.

The answer could lie in the game that genes play during sexual recombination, and computer theorists at the University of California, Berkeley, have identified an algorithm ...

Quantum biology: Algae evolved to switch quantum coherence on and off

2014-06-16

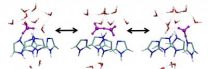

A UNSW Australia-led team of researchers has discovered how algae that survive in very low levels of light are able to switch on and off a weird quantum phenomenon that occurs during photosynthesis.

The function in the algae of this quantum effect, known as coherence, remains a mystery, but it is thought it could help them harvest energy from the sun much more efficiently.

Working out its role in a living organism could lead to technological advances, such as better organic solar cells and quantum-based electronic devices.

The research is published in the journal Proceedings ...

Quantum theory reveals puzzling pattern in how people respond to some surveys

2014-06-16

COLUMBUS, Ohio – Researchers used quantum theory – usually invoked to describe the actions of subatomic particles – to identify an unexpected and strange pattern in how people respond to survey questions.

By conventional standards, the results are surprising: The scientists found the exact same pattern in 70 nationally representative surveys from Gallup and the Pew Research center taken from 2001 to 2011, as well as in two laboratory experiments. Most of the national surveys included more than 1,000 respondents in the United States.

"Human behavior is very sensitive ...

Computation leads to better understanding of influenza virus replication

2014-06-16

Treating influenza relies on drugs such as Amantadine that are becoming less and less effective due to viral evolution. But University of Chicago scientists have published computational results that may give drug designers the insight they need to develop the next generation of effective influenza treatment.

"It's very hard to design a drug if you don't understand how the disease functions," said Gregory Voth, the Haig P. Papazian Distinguished Service Professor in Chemistry. Voth and three co-authors offer new insights into the disease's functioning in the Proceedings ...