(Press-News.org) One of the great mysteries of anesthesia is how patients can be temporarily rendered completely unresponsive during surgery and then wake up again, with their memories and skills intact.

A new study by Dr. Andrew Hudson, an assistant professor in anesthesiology at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, and colleagues provides important clues about the processes used by structurally normal brains to navigate from unconsciousness back to consciousness. Their findings are currently available in the early online edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Previous research has shown that the anesthetized brain is not "silent" under surgical levels of anesthesia but experiences certain patterns of activity, and it spontaneously changes its activity patterns over time, Hudson said.

For the current study, the research team recorded the electrical activity from several brain areas associated with arousal and consciousness in a rodent model that had been given the inhaled anesthetic isoflurane. They then slowly decreased the amount of anesthesia, as is done with patients in the operating room, monitoring how the electrical activity in the brain changed and looking for common activity patterns across all the study subjects.

The researchers found that the brain activity occurred in discrete clumps, or clusters, and that the brain did not jump between all of the clusters uniformly.

A small number of activity patterns consistently occurred in the anesthetized rodents, Hudson noted. The patterns depended on how much anesthesia the subject was receiving, and the brain would jump spontaneously from one activity pattern to another. A few activity patterns served as "hubs" on the way back to consciousness, connecting activity patterns consistent with deeper anesthesia to those observed under lighter anesthesia.

"Recovery from anesthesia is not simply the result of the anesthetic 'wearing off,' but also of the brain finding its way back through a maze of possible activity states to those that allow conscious experience," Hudson said. "Put simply, the brain reboots itself."

The study suggests a new way to think about the human brain under anesthesia, and could encourage physicians to reexamine how they approach monitoring anesthesia in the operating room. Additionally, if the results are applicable to other disorders of consciousness — such as coma or minimally conscious states — doctors may be better able to predict functional recovery from brain injuries by looking at the spontaneously occurring jumps in brain activity.

In addition, this work provides some constraints for theories about how the brain leads to consciousness itself, Hudson said.

Going forward, the UCLA researchers will test other anesthetic agents to determine if they produce similar characteristic brain activity patterns with "hub" states. They also hope to better characterize how the brain jumps between patterns.

INFORMATION:

Other authors include Diany Paola Calderon and Donald W. Pfaff of Rockefeller University in New York and Alex Proekt of the Weill Cornell Medical College in New York.

The research was supported by a Foundation for Anesthesia Education and Research grant and K08 (GM106144-01) and an American Association of University Women International fellowship.

Study examines how brain 'reboots' itself to consciousness after anesthesia

2014-06-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Scripps Florida scientists pinpoint how genetic mutation causes early brain damage

2014-06-18

JUPITER, FL, June 18, 2014 – Scientists from the Florida campus of The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) have shed light on how a specific kind of genetic mutation can cause damage during early brain development that results in lifelong learning and behavioral disabilities. The work suggests new possibilities for therapeutic intervention.

The study, which focuses on the role of a gene known as Syngap1, was published June 18, 2014, online ahead of print by the journal Neuron. In humans, mutations in Syngap1 are known to cause devastating forms of intellectual disability ...

Blocking brain's 'internal marijuana' may trigger early Alzheimer's deficits, study shows

2014-06-18

A new study led by investigators at the Stanford University School of Medicine has implicated the blocking of endocannabinoids — signaling substances that are the brain's internal versions of the psychoactive chemicals in marijuana and hashish — in the early pathology of Alzheimer's disease.

A substance called A-beta — strongly suspected to play a key role in Alzheimer's because it's the chief constituent of the hallmark clumps dotting the brains of people with Alzheimer's — may, in the disease's earliest stages, impair learning and memory by blocking the natural, beneficial ...

Groundbreaking model explains how the brain learns to ignore familiar stimuli

2014-06-18

Dublin, June 18th, 2014 – A neuroscientist from Trinity College Dublin has proposed a new, ground-breaking explanation for the fundamental process of 'habituation', which has never been completely understood by neuroscientists.

Typically, our response to a stimulus is reduced over time if we are repeatedly exposed to it. This process of habituation enables organisms to identify and selectively ignore irrelevant, familiar objects and events that they encounter again and again. Habituation therefore allows the brain to selectively engage with new stimuli, or those that ...

Fight-or-flight chemical prepares cells to shift brain from subdued to alert

2014-06-18

A new study from The Johns Hopkins University shows that the brain cells surrounding a mouse's neurons do much more than fill space. According to the researchers, the cells, called astrocytes because of their star-shaped appearance, can monitor and respond to nearby neural activity, but only after being activated by the fight-or-flight chemical norepinephrine. Because astrocytes can alter the activity of neurons, the findings suggest that astrocytes may help control the brain's ability to focus.

The study involved observing the cells in the brains of living, active mice ...

Modeling how neurons work together

2014-06-18

A newly-developed, highly accurate representation of the way in which neurons behave when performing movements such as reaching could not only enhance understanding of the complex dynamics at work in the brain, but aid in the development of robotic limbs which are capable of more complex and natural movements.

Researchers from the University of Cambridge, working in collaboration with the University of Oxford and the Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), have developed a new model of a neural network, offering a novel theory of how neurons work together when ...

Stem pipeline problems to aid STEM diversity

2014-06-18

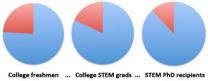

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Decades of effort to increase the number of minority students entering the metaphorical science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) pipeline, haven't changed this fact: Traditionally underrepresented groups remain underrepresented. In a new paper in the journal BioScience, two Brown University biologists analyze the pipeline's flawed flow and propose four research-based ideas to ensure that more students emerge from the far end with Ph.D.s and STEM careers.

Senior author Andrew G. Campbell, associate professor of biology, said ...

Nanoparticles from dietary supplement drinks likely to reach environment, say scientists

2014-06-18

Nanoparticles are becoming ubiquitous in food packaging, personal care products and are even being added to food directly. But the health and environmental effects of these tiny additives have remained largely unknown. A new study now suggests that nanomaterials in food and drinks could interfere with digestive cells and lead to the release of the potentially harmful substances to the environment. The report on dietary supplement drinks containing nanoparticles was published in the journal ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering.

Robert Reed and colleagues note that food ...

BU-lead study shows surprising spread of spring leaf-out times

2014-06-18

(Boston) – Despite conventional wisdom among gardeners, foresters and botanists that woody plants all "leaf out" at about the same time each spring, a new study organized by a Boston University biologist found a surprisingly wide span of as much as three months in leaf-out times. Significantly, observations the past two springs of 1,597 woody plants in eight botanical gardens in the U.S., Canada, Germany and China suggest that species differences in leaf-out times could impact the length of the growing season and the activities of birds, insect and other animals and therefore ...

Innovative technologies in rural areas improve agriculture, health care

2014-06-18

TAMPA, Fla. (June 18, 2014) – The current special issue of Technology and Innovation is devoted to articles on both innovations in rural regions and general articles on technology and innovation, including an article from the National Academy of Inventors (NAI) by McDevitt et al. that discusses the value of technology transfer for universities beyond money.

The five papers in this special issue of Technology and Innovation dealing with innovations in rural regions include an editorial, an analysis of the value of networks for European organic farmers and conventional ...

Self-repairing mechanism can help to preserve brain function in neurodegenerative diseases

2014-06-18

New research, led by scientists at the University of Southampton, has found that neurogenesis, the self-repairing mechanism of the adult brain, can help to preserve brain function in neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's, Prion or Parkinson's.

The progressive degeneration and death of the brain, occurring in many neurodegenerative diseases, is often seen as an unstoppable and irrevocable process. However, the brain has some self-repairing potential that accounts for the renewal of certain neuronal populations living in the dentate gyrus, a simple cortical region ...