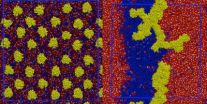

(Press-News.org) Supercomputer simulations have shown that clusters of a protein linked to cancer warp cell membranes, according to scientists at The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth) Medical School. This research on these protein clusters, or aggregates as scientists call them, could help guide design of new anticancer drugs.

"The aggregate is a large substructure that imposes some kind of curvature on the membrane — that's really the major observation," said Alemayehu Gorfe, assistant professor of Integrative Biology and Pharmacology at the UTHealth Medical School.

Gorfe led the study published in the Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters in April 2014. They created coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulations of the Ras protein using the Lonestar and Stampede supercomputers at the Texas Advanced Computing Center, one of the nation's leading academic supercomputer centers and part of The University of Texas at Austin.

"Without these two machines, the work in this paper and our other recent publications would not have been possible. TACC was key to this project," Gorfe said. The University of Texas System Research Cyberinfrastructure (UTRC) facilitated the computing resources used by his research group. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) funded the study.

More than one-third of all human cancers are associated with somatic, or post-conception, mutations in Ras proteins, according to the NIH. "Mutations on one of the Ras proteins, Kristen or K-Ras, are responsible for 90 percent or more of pancreatic cancer cases," Gorfe said. "It tells you that it is a very, very important anticancer drug target."

The Ras gene, which codes for the Ras proteins, was discovered in the 1960s, and represents the first gene identified with the potential to cause cancer in humans. Ras gets its name from the rat sarcoma virus, where it was first identified. Scientists believe Ras proteins mediate a chain of cell signals that can cause out of control cell reproduction and ultimately cancer. Scientists today have little understanding of how or what happens when Ras proteins form small, nano-sized clusters on the membrane. The researchers hope that a better understanding of how Ras proteins cluster together and interact with other proteins in cells will bring them one step closer to developing therapeutic targets for Ras-driven tumors.

"It is these nanoclusters, these transient substructures on the cell membrane that assemble and disassemble quickly, that are involved in signal transmission," Gorfe said.

Gorfe's computer simulations showed Ras proteins cluster together, or form aggregates, on the cell membrane. And this led him to question what they might do there.

"Would the proteins just sit passively and not affect the membrane at all? Or would they somehow change its shape? That is the question we asked," Gorfe said. "The observation was clearly that they have a major effect on the membrane."

When the normally flat bilayer of the cell membrane gets drastically curved, scientists call it membrane remodeling. Membrane remodeling typically occurs during cell division, during cell movement as it slithers around, and during vesicle formation, when a small piece buds off like what you might see in a lava lamp.

On a smaller scale, the membrane folds and buckles near clusters of Ras proteins. Gorfe said that understanding the dynamics of Ras proteins is critical to its study as a potential drug target for cancer.

"One of the major contributions, in my view, of molecular dynamics simulations is the information we get using this method about the dynamics of biomolecules in general," Gorfe said.

What's more, simulations are useful for structure-based, computer-aided drug design. "We try to use these snapshots of the moving protein, or an ensemble of structures, to dock small molecules in a virtual screening setting," Gorfe explained. Docking refers to the process of a drug molecule attaching itself to the surface of a protein. "Of course, if we develop inhibitors starting with these kinds of studies that would help treat cancer, that would be wonderful."

Priyanka Srivastava researches the Ras protein with Gorfe in his lab as a Keck Postdoctoral Fellow at UTHealth. "Our ultimate goal is to identify novel pockets that transiently open during protein motion but are hidden in the average experimental Ras structure so that we can target those," Srivastava said.

For more than 40 years, scientists have known that Ras is a cancer-causing protein but have been unable to stop it. Ras acts like a switch that must be turned on for cells to reproduce. The problem is that when RAS genes get mutated, that switch just won't turn off, and that leads to out of control cell growth.

"In the 1990s, there was a lot of excitement about a class of compounds that inhibit one of the enzymes that puts lipids on Ras proteins," Gorfe said, "and lipidation is important for membrane binding of the protein. The thought was, if we inhibit one of the enzymes that actually puts lipids on Ras, we might dislodge it from the membrane surface, or we might be able to prevent it from membrane binding, and in so doing prevent its function."

These compounds failed because Ras is tricky. "If you knock out one of the enzymes that it uses, it just finds another to bind itself to the membrane," he explained.

For this and other reasons, Ras was considered undruggable, according to Gorfe. Interest in Ras as an anticancer drug target faded. Hope in targeting Ras has sprung up in the last five years due in large part to simulations and analyses enabled by supercomputers.

"We learned quite a bit about the importance of dynamics in drug discovery in general and for Ras proteins, in particular," Gorfe said. "The dynamics came into the picture."

Understanding the dynamics will help scientists reveal the vulnerable spots of the Ras molecule, according to Srivastava.

"Using TACC resources, we carried out an atomic-level simulation of membrane-bound K-Ras. And it was very interesting that it actually revealed new binding sites that had not been previously characterized. At this point in time we are doing site-directed virtual screening against these sites, which may result in some sort of promising anticancer drug."

"Uncovering new membrane binding sites on Ras may lead to a greater understanding of how its on-off switch is controlled and how to specifically inhibit the unregulated cell growth in cancers caused by defective Ras," said Jean Chin, program director in the Division of Cell Biology and Biophysics of the National Institute of Health's National Institute of General Medical Sciences, which funded the research. "These simulations by Dr. Gorfe will also provide new models and ideas for his colleagues and other biologists to test experimentally."

Another advance was the realization earlier by Gorfe in collaboration with J. Andrew McCammon of the University of California at San Diego and Barry Grant of the University of Michigan, as well as other scientists, that Ras is what's called an allosteric enzyme.

"What that means is that binding of small molecules further away from the part of the protein that's actually involved with the interaction with other proteins or substrates — that's what you want to prevent — impacts interaction via other parts of the protein."

Simulations — and computational modeling in general — have become an integral part of modern research in biology, according to Gorfe.

"In some cases, information that you would not be able to get from experimental methods alone can be obtained from simulations. Therefore, simulations can combine with experiments to provide detailed insights into how Ras proteins work in the cell. In this regard, we are fortunate to have a long-standing collaboration with experimental biologists, and I would like to especially thank Dr. John F. Hancock and members of his laboratory here in our school. With the level of advances in algorithms, infrastructure, and computer speed, we have begun to ask more fundamental questions and to use more complicated model systems," he added.

And for the millions of people worldwide who suffer from Ras-associated cancers, those answers couldn't come sooner.

INFORMATION:

Cancer chain in the membrane

Supercomputing simulations crucial to the study of Ras protein in determining anticancer drugs

2014-06-23

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Working parents resort to emergency or urgent care visits to get kids back into child care

2014-06-23

Ann Arbor, Mich. — Substantial proportions of parents chose urgent care or emergency department visits when their sick children were excluded from attending child care, according to a new study by University of Michigan researchers.

The study, published today in Pediatrics, also found that use of the emergency department or urgent care was significantly higher among parents who are single or divorced, African American, have job concerns or needed a doctor's note for the child to return.

Previous studies have shown children in child care are frequently ill with mild ...

Fungal infection control methods for lucky bamboo

2014-06-23

GAINESVILLE, FL – The popularity of ornamental plants imported to the United States from China is accompanied by concerns about the potential to introduce pathogens into the market. Dracaena, a genus consisting of approximately 40 different species, including the widely recognized "lucky bamboo," is among the most frequently imported group of ornamentals to enter the U.S. for domestic sale and eventual export to Canada. The authors of a new research study say it is crucial to be vigilant about potential pests and pathogens on imported cuttings of Dracaena. "Pests and pathogens ...

Cautionary tales: Mustaches, home oxygen therapy, sparks do not mix

2014-06-23

Rochester, Minn. — Facial hair and home oxygen therapy can prove a dangerously combustible combination, a Mayo Clinic report published in the peer-reviewed medical journal Mayo Clinic Proceedings finds. To reach that conclusion, researchers reviewed home oxygen therapy-related burn cases and experimented with a mustachioed mannequin, a facial hair-free mannequin, nasal oxygen tubes and sparks. They found that facial hair raises the risk of home oxygen therapy-related burns, and encourage health care providers to counsel patients about the risk.

MULTIMEDIA ALERT: Video ...

Africa's poison 'apple' provides common ground for saving elephants, raising livestock

2014-06-23

VIDEO:

A five-year study led by Robert Pringle (above), a Princeton University assistant professor of ecology and evolutionary biology, suggests that certain wild African animals, particularly elephants, could be a boon...

Click here for more information.

While African wildlife often run afoul of ranchers and pastoralists securing food and water resources for their animals, the interests of fauna and farmer might finally be unified by the "Sodom apple," a toxic invasive plant ...

Back away, please

2014-06-23

In our long struggle for survival, we humans learned that something approaching us is far more of a threat than something that is moving away. This makes sense, since a tiger bounding toward a person is certainly more of a threat than one that is walking away.

Though we modern humans don't really consider such fear, it turns out that it still plays a big part in our day-to-day lives. According to University of Chicago Booth School of Business Professor Christopher K. Hsee, we still have negative feelings about things that approach us — even if they objectively are not ...

Wearable computing gloves can teach Braille, even if you're not paying attention

2014-06-23

Several years ago, Georgia Institute of Technology researchers created a technology-enhanced glove that can teach beginners how to play piano melodies in 45 minutes. Now they've advanced the same wearable computing technology to help people learn how to read and write Braille. The twist is that people wearing the glove don't have to pay attention. They learn while doing something else.

"The process is based on passive haptic learning (PHL)," said Thad Starner, a Georgia Tech professor and wearable computer pioneer. "We've learned that people can acquire motor skills ...

Can magnetic fields accurately measure positions of ferromagnetic objects?

2014-06-23

Many creatures in nature, including butterflies, newts and mole rats, use the Earth's inherent magnetic field lines and field intensity variations to determine their geographical position. A research team at the University of Minnesota has shown that the inherent magnetic fields of ferromagnetic objects can be similarly exploited for accurate position measurements of these objects. Such position measurement is enabled in this research by showing that the spatial variation of magnetic field around an object can be modeled using just the geometry of the object under consideration. ...

Breakthrough drug-eluting patch stops scar growth and reduces scar tissues

2014-06-23

Scars — in particular keloid scars that result from overgrowth of skin tissue after injuries or surgeries — are unsightly and can even lead to disfigurement and psychological problems of affected patients. Individuals with darker pigmentation — in particular people with African, Hispanic or South-Asian genetic background — are more likely to develop this skin tissue disorder. Current therapy options, including surgery and injections of corticosteroids into scar tissues, are often ineffective, require clinical supervision and can be costly.

A new invention by researchers ...

D-Wave and predecessors: From simulated to quantum annealing

2014-06-23

The D-Wave computer is currently the latest link of a long chain of computers designed for the solution of optimization problems. In what sense does it realize quantum computation? We describe the evolution of such computers and confront the different views concerning the quantum properties of the D-wave computer.

Quantum algorithms show several benefits over classical ones. One strong example suggested by Shor in 1994 is the ability to factor numbers which can be effectively done on a quantum computer but is very hard on a classical computer. However, the actual model ...

New data bolsters Higgs boson discovery

2014-06-23

If evidence of the Higgs boson revealed two years ago was the smoking gun, particle physicists at Rice University and their colleagues have now found a few of the bullets.

The European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) published research in Nature Physics this week that details evidence of the direct decay of the Higgs boson to fermions, among the particles anticipated by the Standard Model of physics.

The finding fits what researchers expected to see amid the massive amount of data provided by the Large Hadron Collider (LHC). The world's largest collider smashed ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

Yes! The role of YAP and CTGF as potential therapeutic targets for preventing severe liver disease

Pancreatic cancer may begin hiding from the immune system earlier than we thought

Robotic wing inspired by nature delivers leap in underwater stability

A clinical reveals that aniridia causes a progressive loss of corneal sensitivity

Fossil amber reveals the secret lives of Cretaceous ants

Predicting extreme rainfall through novel spatial modeling

The Lancet: First-ever in-utero stem cell therapy for fetal spina bifida repair is safe, study finds

Nanoplastics can interact with Salmonella to affect food safety, study shows

Eric Moore, M.D., elected to Mayo Clinic Board of Trustees

NYU named “research powerhouse” in new analysis

New polymer materials may offer breakthrough solution for hard-to-remove PFAS in water

Biochar can either curb or boost greenhouse gas emissions depending on soil conditions, new study finds

Nanobiochar emerges as a next generation solution for cleaner water, healthier soils, and resilient ecosystems

Study finds more parents saying ‘No’ to vitamin K, putting babies’ brains at risk

Scientists develop new gut health measure that tracks disease

Rice gene discovery could cut fertiliser use while protecting yields

Jumping ‘DNA parasites’ linked to early stages of tumour formation

[Press-News.org] Cancer chain in the membraneSupercomputing simulations crucial to the study of Ras protein in determining anticancer drugs