Delivering drugs on cue

Harvard team uses ultrasound and self-healing hydrogels to noninvasively deliver drugs at the right place and the right time -- and shows that periodic drug bursts may enhance chemotherapy treatment

2014-06-23

(Press-News.org) June 23, Boston -- Current drug-delivery systems used to administer chemotherapy to cancer patients typically release a constant dose of the drug over time - but a new study challenges this "slow and steady" approach and offers a novel way to locally deliver the drugs "on demand," as reported in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

Led by David J. Mooney, Ph.D., a Core Faculty member at Harvard's Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering and the Robert P. Pinkas Family Professor of Bioengineering at the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS), the team loaded a biocompatible hydrogel with a chemotherapy drug and used ultrasound to trigger the gel to release the drug. Like many other injectable gels that have been used for drug delivery for decades, this one gradually releases a low level of the drug by diffusion over time. To temporarily increase doses of drug, scientists had previously applied ultrasound -- but that approach was a one-shot deal as the ultrasound was used to destroy those gels.

This gel was different.

The team used ultrasound to temporarily disrupt the gel such that it released short, high-dose bursts of the drug - akin to opening up a floodgate. But when they stopped the ultrasound, the hydrogels self-healed. By closing back up, they were ready to go for the next "on demand" drug burst - providing an innovative way to administer drugs with a far greater level of control than possible before.

That's not all. The team also demonstrated in lab cultures and in mice with breast cancer tumors that the pulsed, ultrasound-triggered hydrogel approach to drug delivery was more effective at stopping the growth of tumor cells than traditional, sustained-release drug therapy.

"Our approach counters the whole idea of sustained drug release, and offers a double whammy," said Mooney. "We have shown that we can use the hydrogels repeatedly and turn the drug pulses on and off at will, and that the drug bursts in concert with the baseline low-level drug delivery seems to be particularly effective in killing cancer cells."

The advance holds promising implications for improved cancer treatment and other therapies requiring drugs to be delivered at the right place and the right time -- from post-surgery pain medications to protein-based drugs that require daily injections. It requires an initial injection of the hydrogel, but the approach could be a much less traumatic, minimally invasive and more effective method of drug delivery overall, Mooney said.

"We want to give clinicians the ability to deliver drugs as locally as possible combined with the flexibility to temporally control the dose," said co-lead author Nathanial Huebsch, Ph.D., who was a Harvard SEAS graduate student in the Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology at the time of the research and is now a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Gladstone Institute of Cardiovascular Disease in San Francisco. For example, many cancer patients require a regular dose of pain killers, but unpredictable pain attacks require them to take much larger doses over a short time.

Key to the team's success in designing a hydrogel that self-heals is choosing the right kind of hydrogel with the right kind of drug - and applying the right intensity of ultrasound.

"We were able to trigger our system with a level of ultrasound that was much lower than high-intensity focused ultrasound that is used clinically to heat and destroy tumors," said co-lead author Cathal Kearney, Ph.D., who was a Postdoctoral Fellow at SEAS at the time of the study. He is now a Senior Research Fellow at the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland (RCSI). "The careful selection of materials and properties make it a reversible process," Kearney said.

The team carried out the majority of their work for this study with a gel made out of alginate, a natural polysaccharide from algae that is held together with calcium ions. In a series of laboratory tests they found that with the right level of ultrasound, the bonds break up and enable the gel to release its drug cargo - but as long as the gel in in the presence of more calcium, the bonds reform and the gels self-heal.

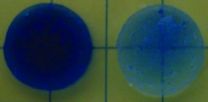

Once the team knew the gel would self-heal, they tested out a drug they suspected it would hold well - in this case a chemotherapy drug called mitoxantrone, which is often used to treat breast cancer. Sure enough, the ultrasound triggered the gel to release the blue-colored drug, as indicated by the newly blue color of the surrounding medium. Just a single ultrasound dose was effective, and the gel reformed after it was disrupted, making multiple cycles possible.

Next, they tested the treatment on mice that had human breast cancer tumors implanted in their bodies. They injected the drug-laden gel close to the tumors, and over the course of six months the mice that received a low-level sustained release of the drug with a daily concentrated pulse of ultrasound (just 2.5 minutes) fared significantly better than mice treated the same but without ultrasound. In contrast to the other groups, the tumors in the ultrasound-treated mice did not grow substantially and the mice survived for an additional 80 days to boot.

"These results demonstrate how applying novel engineering approaches and programmable nanomaterials can create entirely new solutions to critical medical problems," said Wyss Institute Founding Director Don Ingber, M.D., Ph.D., who is also the Judah Folkman Professor of Vascular Biology at Harvard Medical School and Boston Children's Hospital, and Professor of Bioengineering at Harvard SEAS. "Dave's work shows that these new responsive hydrogels that remodel reversibly when exposed to ultrasound energy at the nanoscale not only provide a new way to administer drugs on demand, they also produce better responses to therapy even in a disease as difficult to treat as cancer."

This advance to use simple ultrasound pulses and readily available hydrogels in a new way comes on the heels of Mooney's work using low-power lasers to trigger stem cells to regenerate the material that makes up teeth. The team also demonstrated that the gel can release other kinds of cargo as well, including proteins, which lays the groundwork for potentially using these hydrogels for tissue regeneration, and condensed plasmid DNA - suggesting their potential use in gene therapy.

They plan to explore these other potential applications, as well as the possibility of unleashing two different drugs independently from the same hydrogel, said Mooney.

This work was funded by the Materials Research Science and Engineering Center at Harvard University, a California Institute of Medicine Fellowship, and the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, which is one of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

INFORMATION:

About the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University

The Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University uses Nature's design principles to develop bioinspired materials and devices that will transform medicine and create a more sustainable world. Working as an alliance among all of Harvard's Schools, and in partnership with Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston Children's Hospital, Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Massachusetts General Hospital, the University of Massachusetts Medical School, Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital, Boston University, Tufts University, and Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin, the Institute crosses disciplinary and institutional barriers to engage in high-risk research that leads to transformative technological breakthroughs. By emulating Nature's principles for self-organizing and self-regulating, Wyss researchers are developing innovative new engineering solutions for healthcare, energy, architecture, robotics, and manufacturing. These technologies are translated into commercial products and therapies through collaborations with clinical investigators, corporate alliances, and new start-ups.

About the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences

The Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) serves as the connector and integrator of Harvard's teaching and research efforts in engineering, applied sciences, and technology. Through collaboration with researchers from all parts of Harvard, other universities, and corporate and foundational partners, we bring discovery and innovation directly to bear on improving human life and society. For more information, visit: http://seas.harvard.edu. END

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Bone loss persists 2 years after weight loss surgery

2014-06-23

CHICAGO, IL — A new study shows that for at least two years after bariatric surgery, patients continue to lose bone, even after their weight stabilizes. The results—in patients undergoing gastric bypass, the most common type of weight loss surgery—were presented Monday at the joint meeting of the International Society of Endocrinology and the Endocrine Society: ICE/ENDO 2014 in Chicago.

"The long-term consequences of this substantial bone loss are unclear, but it might put them at increased risk of fracture, or breaking a bone," said Elaine Yu, MD, MSc, the study's principal ...

A disease of mistaken identity

2014-06-23

The symptoms of Cushing disease are unmistakable to those who suffer from it – excessive weight gain, acne, distinct colored stretch marks on the abdomen, thighs and armpits, and a lump, or fat deposit, on the back of the neck. Yet the disorder often goes misdiagnosed.

To help combat misdiagnosis, Saleh Aldasouqi, an associate professor in the College of Human Medicine at Michigan State University, is drawing more attention to the rare disease through a case study, which followed a young patient displaying classic, yet more pronounced signs of the condition.

Caused ...

Date labeling confusion contributes to food waste

2014-06-23

Date labeling variations on food products contribute to confusion and misunderstanding in the marketplace regarding how the dates on labels relate to food quality and safety, according to a scientific review paper in the July issue of Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety. This confusion and misunderstanding along with different regulatory date labeling frameworks, may detract from limited regulatory resources, cause financial loss, and contribute to significant food waste.

In the United States, the United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research ...

Understanding the ocean's role in Greenland glacier melt

2014-06-23

The Greenland Ice Sheet is a 1.7 million-square-kilometer, 2-mile thick layer of ice that covers Greenland. Its fate is inextricably linked to our global climate system.

In the last 40 years, ice loss from the Greenland Ice Sheet increased four-fold contributing to one-quarter of global sea level rise. Some of the increased melting at the surface of the ice sheet is due to a warmer atmosphere, but the ocean's role in driving ice loss largely remains a mystery.

Research by scientists at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) and the Univ. of Oregon sheds new light ...

Protecting and connecting the Flathead National Forest

2014-06-23

A new report from the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) calls for completing the legacy of Wilderness lands on the Flathead National Forest in Montana. The report identifies important, secure habitats and landscape connections for five species—bull trout, westslope cutthroat trout, grizzly bears, wolverines, and mountain goats. These iconic species are vulnerable to loss of secure habitat from industrial land uses and/or climate change.

Located in northwest Montana adjacent to Glacier National Park, the 2.4 million-acre Flathead Forest is a strategic part of the stunning ...

Ferroelectric switching seen in biological tissues

2014-06-23

Measurements taken at the molecular scale have for the first time confirmed a key property that could improve our knowledge of how the heart and lungs function.

University of Washington researchers have shown that a favorable electrical property is present in a type of protein found in organs that repeatedly stretch and retract, such as the lungs, heart and arteries. These findings are the first that clearly track this phenomenon, called ferroelectricity, occurring at the molecular level in biological tissues.

The researchers published their findings online June 23 ...

Grinding away at history using 'forensic' paleontology and archeology

2014-06-23

Tulsa, Ok. – The Society for Sedimentary Geology (SEPM) announces an unusual paper in their journal PALAIOS that combines 'forensic' paleontology and archeology to identify origins of the millstones commonly used in the 1800's. While all millstones were used similarly, millstones quarried in France were more highly valued than similar stones quarried in Ohio, USA.

Over four years the scientific team located millstones by visiting historical localities in Ohio, then studied them and identified unique characteristics between the coveted French buhr and the locally sourced ...

By any stretch

2014-06-23

After their hectic experience of delivery, newborns are almost immediately stretched out on a measuring board to assess their length. Medical staff, reluctant to cause infants discomfort, are tasked with measuring their length, because it serves as an indispensable marker of growth, health and development. But the inaccuracy and unreliability of current measurement methods restrict their use, so routine measurements are often not performed.

Now Tel Aviv University researchers have taken a 21st century approach to the problem, using new software that harnesses computer ...

UCI study finds that learning by repetition impairs recall of details

2014-06-23

Irvine, Calif., June 23, 2014 — When learning, practice doesn't always make perfect.

UC Irvine neurobiologists Zachariah Reagh and Michael Yassa have found that while repetition enhances the factual content of memories, it can reduce the amount of detail stored with those memories. This means that with repeated recall, nuanced aspects may fade away.

In the study, which appears this month in Learning & Memory, student participants were asked to look at pictures either once or three times. They were then tested on their memories of those images. The researchers found ...

For gastric bypass patients, percent of weight loss differs by race/ethnicity, study finds

2014-06-23

PASADENA, Calif., June 20, 2014 – Non-Hispanic white patients who underwent a gastric bypass procedure lost slightly more weight over a three-year period than Hispanic or black patients, according to a Kaiser Permanente study published in the journal Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases. The study also examined two types of bariatric surgery and found that patients who underwent the now common gastric bypass procedure lost more weight over the same period than patients who underwent the more recently developed vertical sleeve gastrectomy procedure.

Researchers examined ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Bacteria frozen in ancient underground ice cave found to be resistant against 10 modern antibiotics

Rhododendron-derived drugs now made by bacteria

Admissions for child maltreatment decreased during first phase of COVID-19 pandemic, but ICU admissions increased later

Power in motion: transforming energy harvesting with gyroscopes

Ketamine high NOT related to treatment success for people with alcohol problems, study finds

1 in 6 Medicare beneficiaries depend on telehealth for key medical care

Maps can encourage home radon testing in the right settings

Exploring the link between hearing loss and cognitive decline

Machine learning tool can predict serious transplant complications months earlier

Prevalence of over-the-counter and prescription medication use in the US

US child mental health care need, unmet needs, and difficulty accessing services

Incidental rotator cuff abnormalities on magnetic resonance imaging

Sensing local fibers in pancreatic tumors, cancer cells ‘choose’ to either grow or tolerate treatment

Barriers to mental health care leave many children behind, new data cautions

Cancer and inflammation: immunologic interplay, translational advances, and clinical strategies

Bioactive polyphenolic compounds and in vitro anti-degenerative property-based pharmacological propensities of some promising germplasms of Amaranthus hypochondriacus L.

AI-powered companionship: PolyU interfaculty scholar harnesses music and empathetic speech in robots to combat loneliness

Antarctica sits above Earth’s strongest “gravity hole.” Now we know how it got that way

Haircare products made with botanicals protects strands, adds shine

Enhanced pulmonary nodule detection and classification using artificial intelligence on LIDC-IDRI data

Using NBA, study finds that pay differences among top performers can erode cooperation

Korea University, Stanford University, and IESGA launch Water Sustainability Index to combat ESG greenwashing

Molecular glue discovery: large scale instead of lucky strike

Insulin resistance predictor highlights cancer connection

Explaining next-generation solar cells

Slippery ions create a smoother path to blue energy

Magnetic resonance imaging opens the door to better treatments for underdiagnosed atypical Parkinsonisms

National poll finds gaps in community preparedness for teen cardiac emergencies

One strategy to block both drug-resistant bacteria and influenza: new broad-spectrum infection prevention approach validated

Survey: 3 in 4 skip physical therapy homework, stunting progress

[Press-News.org] Delivering drugs on cueHarvard team uses ultrasound and self-healing hydrogels to noninvasively deliver drugs at the right place and the right time -- and shows that periodic drug bursts may enhance chemotherapy treatment