(Press-News.org) An international team of scientists studying Emperor penguin populations across Antarctica finds the iconic animals in danger of dramatic declines by the end of the century due to climate change. Their study, published today in Nature Climate Change, finds the Emperor penguin "fully deserving of endangered status due to climate change."

The Emperor penguin is currently under consideration for inclusion under the US Endangered Species Act. Criteria to classify species by their extinction risk are based on the global population dynamics.

The study was conducted by lead author Stephanie Jenouvrier, a biologist with the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), and colleagues at the Centre d'Etudes Biologiques de Chizé (French Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique), the National Center for Atmospheric Research, the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences, and the University of Amsterdam.

Emperor penguins are heavily dependent on sea ice for their livelihoods, and, therefore, are sensitive to changes in sea ice concentration (SIC). The researchers' analysis of the global, continent-wide Emperor penguin population incorporates current and projected future SIC declines, and determined that all of the colonies would be in decline – many by more than 50 percent – by the end of the century, due to future climate change.

"If sea ice declines at the rates projected by the IPCC climate models, and continues to influence Emperor penguins as it did in the second half of the 20th century in Terre Adélie, at least two-thirds of the colonies are projected to have declined by greater than 50 percent from their current size by 2100," said Jenouvrier. "None of the colonies, even the southern-most locations in the Ross Sea, will provide a viable refuge by the end of 21st century."

The foundation for the research is a 50-year intensive study of the Emperor penguin colony in Terre Adélie, in eastern Antarctica, supported by the French Polar Institute (IPEV) and Zone Atelier Antarctique (LTER France). Researchers have been returning to Terre Adélie every year to collect biological measurements of the penguins there, charting the population's growth (and decline), and observing their mating, foraging, chick-rearing patterns, and following marked individuals from year to year.

"Long-term studies like this are invaluable for measuring the response of survival and breeding to changes in sea ice. They provide our understanding of the role sea ice plays in the emperor penguin's life cycle," said Hal Caswell, a scientist emeritus at WHOI and professor at the University of Amsterdam.

"The role of sea ice is complicated," added Jenouvrier. "Too much ice requires longer trips for penguin parents to travel to the ocean to hunt and bring back food for their chicks. But too little ice reduces the habitat for krill, a critical food source for emperor penguins. Our models take into account both the effects of too much and too little sea ice in the colony area."

The data from Terre Adélie were an essential component of two earlier studies by Jenouvrier, Caswell, and their team: a 2009 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academies of Science and a more detailed 2012 study in Global Change Biology that showed the Terre Adélie population was likely to decline by 80 percent by the end of the century.

The new study expands on that work, by using the previous population models to project how all of Antarctica's 45 known colonies will respond to future climate change. Those projections are based on the current SIC at each location and on changes in SIC at each location, projected by the best available climate models. Those models, part of the IPCC effort, incorporate the physical processes in the atmosphere, ocean, cryosphere and land surfaces.

The researchers found that, while some colonies will increase for a while, this growth is short-lived. By the end of the century at least two-thirds of them will have declined by more than half. Of even more concern, all of the colonies are projected to be declining by that time. Although current climate models do not look further into the future than that, a dramatic change would be required to reverse these declines.

Based on their research, the study's authors state: "We propose that the Emperor penguin is fully deserving of endangered status due to climate change, and can act as an iconic example of a new global conservation paradigm for species threatened by future climate change."

The team's study acknowledges the special problems of defining conservation criteria for species endangered by future climate change, because the negative effects of climate change may build up over time.

"Listing the Emperor penguin as an endangered species would reflect the scientific assessment of the threats facing an important part of the Antarctic ecosystem under climate change," said Caswell. "When a species is at risk due to one factor – in this case, climate change – it can be helped, sometimes greatly, by amelioration of other factors. That's why the Endangered Species Act is written to protect an endangered species in a number of ways – exploitation, habitat, disturbance, etc. – even if those factors are not the cause of its current predicament."

"Listing the emperor penguin will provide some tools to improve fishing practices of US vessels in the Southern Ocean, and gives a potential tool to help reduce CO2 emissions in the US under the Clear Air and Clean Water Acts," Jenouvrier said.

The authors offer recommendations and considerations for new international conservation paradigms, including the identification of potential refuges for preserving populations. They point out that Ross Sea will be the last place impacted by climate change, and that conservation management strategies should focus there.

INFORMATION:

The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution is a private, independent organization on Cape Cod, Mass., dedicated to marine research, engineering, and higher education. Established in 1930 on a recommendation from the National Academy of Sciences, its primary mission is to understand the ocean and its interaction with the Earth as a whole, and to communicate a basic understanding of the ocean's role in the changing global environment. For more information, please visit http://www.whoi.edu.

The Centre d'Etudes Biologiques de Chizé is a public research laboratory from the French National Centre for Scientific Research and the University of La Rochelle, France, dedicated to the study of the ecology, evolution and conservation of vertebrate populations. For more information, please visit http://www.cebc.cnrs.fr.

The French Polar Institute (IPEV) is a public funding and logistics agency dedicated to polar research. For more information, please visit http://www.institut-polaire.fr.

The Zone Atelier Antarctique (ZATA) is a public long term ecological research federation supporting long term research programs in polar ecosystems. For more information, please visit za-antarctique.univ-rennes1.fr.

Study finds Emperor penguin in peril

2014-06-29

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Noninvasive brain control

2014-06-29

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Optogenetics, a technology that allows scientists to control brain activity by shining light on neurons, relies on light-sensitive proteins that can suppress or stimulate electrical signals within cells. This technique requires a light source to be implanted in the brain, where it can reach the cells to be controlled.

MIT engineers have now developed the first light-sensitive molecule that enables neurons to be silenced noninvasively, using a light source outside the skull. This makes it possible to do long-term studies without an implanted light source. ...

Bending the rules

2014-06-29

(Santa Barbara, Calif.) — For his doctoral dissertation in the Goldman Superconductivity Research Group at the University of Minnesota, Yu Chen, now a postdoctoral researcher at UC Santa Barbara, developed a novel way to fabricate superconducting nanocircuitry. However, the extremely small zinc nanowires he designed did some unexpected — and sort of funky — things.

Chen, along with his thesis adviser, Allen M. Goldman, and theoretical physicist Alex Kamenev, both of the University of Minnesota, spent years seeking an explanation for these extremely puzzling effects. ...

Improved method for isotope enrichment could secure a vital global commodity

2014-06-29

AUSTIN, Texas — Researchers at The University of Texas at Austin have devised a new method for enriching a group of the world's most expensive chemical commodities, stable isotopes, which are vital to medical imaging and nuclear power, as reported this week in the journal Nature Physics. For many isotopes, the new method is cheaper than existing methods. For others, it is more environmentally friendly.

A less expensive, domestic source of stable isotopes could ensure continuation of current applications while opening up opportunities for new medical therapies and fundamental ...

Improved survival with TAS-102 in mets colorectal cancer refractory to standard therapies

2014-06-28

The new combination agent TAS-102 is able to improve overall survival compared to placebo in patients whose metastatic colorectal cancer is refractory to standard therapies, researchers said at the ESMO 16th World Congress on Gastrointestinal Cancer in Barcelona.

"Around 50% of patients with colorectal cancer develop metastases but eventually many of them do not respond to standard therapies," said Takayuki Yoshino of the National Cancer Centre Hospital East in Chiba, Japan, lead author of the phase III RECOURSE trial. "The RECOURSE study shows that TAS-102 improves overall ...

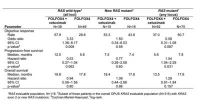

Cetuximab or bevacizumab with combi chemo equivalent in KRAS wild-type MCRC

2014-06-28

For patients with KRAS wild-type untreated colorectal cancer, adding cetuximab or bevacizumab to combination chemotherapy offers equivalent survival, researchers said at the ESMO 16th World Congress on Gastrointestinal Cancer in Barcelona.

"The CALGB/SWOG 80405 trial was designed and formulated in 2005, and the rationale was simple: we had new drugs --bevacizumab and cetuximab-- and the study was designed to determine if one was better than the other in first-line for patients with colon cancer," said lead study author Alan P. Venook, distinguished Professor of Medical ...

Herpes virus infection drives HIV infection among non-injecting drug users in New York

2014-06-27

HIV and its transmission has long been associated with injecting drug use, where hypodermic syringes are used to administer illicit drugs. Now, a newly reported study by researchers affiliated with New York University's Center for Drug Use and HIV Research (CDUHR) in the journal PLOS ONE, shows that HIV infection among heterosexual non-injecting drug users (no hypodermic syringe is used; drugs are taken orally or nasally) in New York City (NYC) has now surpassed HIV infection among persons who inject drugs.

The study, "HSV-2 Co-Infection as a Driver of HIV Transmission ...

Potential Alzheimer's drug prevents abnormal blood clots in the brain

2014-06-27

Without a steady supply of blood, neurons can't work. That's why one of the culprits behind Alzheimer's disease is believed to be the persistent blood clots that often form in the brains of Alzheimer's patients, contributing to the condition's hallmark memory loss, confusion and cognitive decline.

New experiments in Sidney Strickland's Laboratory of Neurobiology and Genetics at Rockefeller University have identified a compound that might halt the progression of Alzheimer's by interfering with the role amyloid-β, a small protein that forms plaques in Alzheimer's brains, ...

'Bad' video game behavior increases players' moral sensitivity

2014-06-27

BUFFALO, N.Y. — New evidence suggests heinous behavior played out in a virtual environment can lead to players' increased sensitivity toward the moral codes they violated.

That is the surprising finding of a study led by Matthew Grizzard, PhD, assistant professor in the University at Buffalo Department of Communication, and co-authored by researchers at Michigan State University and the University of Texas, Austin.

"Rather than leading players to become less moral," Grizzard says, "this research suggests that violent video-game play may actually lead to increased moral ...

Ancient ocean currents may have changed pace and intensity of ice ages

2014-06-27

Climate scientists have long tried to explain why ice-age cycles became longer and more intense some 900,000 years ago, switching from 41,000-year cycles to 100,000-year cycles.

In a paper published this week in the journal Science, researchers report that the deep ocean currents that move heat around the globe stalled or may have stopped at that time, possibly due to expanding ice cover in the Northern Hemisphere.

"The research is a breakthrough in understanding a major change in the rhythm of Earth's climate, and shows that the ocean played a central role," says ...

Research gives unprecedented 3-D view of important brain receptor

2014-06-27

PORTLAND, Ore. — Researchers with Oregon Health & Science University's Vollum Institute have given science a new and unprecedented 3-D view of one of the most important receptors in the brain — a receptor that allows us to learn and remember, and whose dysfunction is involved in a wide range of neurological diseases and conditions, including Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, schizophrenia and depression.

The unprecedented view provided by the OHSU research, published online June 22 in the journal Nature, gives scientists new insight into how the receptor — called the NMDA receptor ...